Supreme Court Justices, During Marathon Oral Arguments, Appear Inclined To Delay J6 Prosecution of Trump Until After Election

Yet Justice Jackson, from the court’s liberal minority, warns that the 45th president’s position could turn the ‘Oval Office into the seat of criminality in this country.’

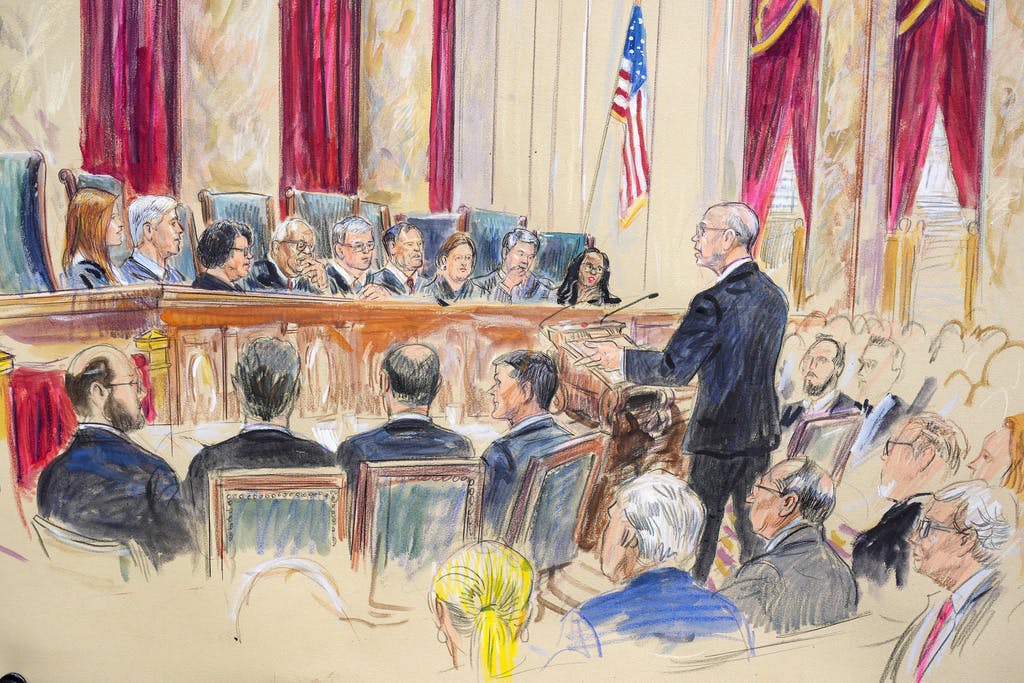

The Supreme Court’s skepticism with respect to President Trump’s claim of absolute immunity could mean he will stand trial for working to overturn the 2020 presidential election. Yet the justices, during a long stretch of oral arguments on Thursday, appeared poised to allow for delays, well past Election Day, in the progress of that criminal case. That would be a victory for Mr. Trump, who could — potentially — pardon himself if he’s re-elected.

Even if the court ultimately comes down on Special Counsel Jack Smith’s side, the path back to Judge Tanya Chutkan’s courtroom for a criminal trial is uncertain. The court’s conservatives telegraphed their concern that the crucial distinction between private and official acts could require further adjudication.

Mr. Trump and Mr. Smith agree that there is no immunity for acts that are purely personal and unrelated to the presidency. Their dispute is whether immunity covers official acts. The 45th president maintains that they do, and the special counsel argues that if criminal, they do not. The high court could direct Judge Chutkan to discern, in what could prove a time-consuming process, the line between the private and the official.

The liberal justices, though, sounded the constitutional alarm. Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson worried that a finding of absolute immunity would turn the “Oval Office into the seat of criminal activity in this country.” She warned of a world where presidents are “emboldened to commit crimes with abandon.” Justice Elena Kagan noted that “The Framers did not put an immunity clause in the Constitution.”

The more than two hours of oral arguments transpired on constitutional bedrock. Mr. Trump’s attorney, John Sauer, declared that “without immunity there can be no presidency.” He warned the Nine that if they formulate a parsimonious view of immunity, every president would stand vulnerable. He speculated that, say, President Biden could be prosecuted for “unlawfully inducing immigrants to enter the country illegally.”

His foe, the veteran Supreme Court advocate Michael Dreeben, a Justice Department lawyer who also worked on Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s Russia probe, warned that an extravagant grant of immunity would amount to an invitation for presidents to commit “bribery, treason, sedition, murder.” He declared that “the Framers knew too well the dangers of a king who could do no wrong” and were not eager to replicate the monarchical model in the nascent Republic.

The oral arguments traversed the scandals of Watergate — Justice Jackson asked “The pardon for President Nixon, what was up with that?” — the intentions of Benjamin Franklin, and even the legacy of the repudiated precedent of Korematsu v. United States, which affirmed the detention of Japanese Americans during wartime. The justices searched for the point where the prerogatives of the presidency end and the accountability of criminal law begins.

The justices displayed interest in constitutional terra incognita, with a conservative justice, Neil Gorsuch, pushing Mr. Dreeben to speak for the Department of Justice on whether presidents can pardon themselves, a question that has never been heard. The attorney demurred, though he conceded that the pardon power is a “core” prerogative of the presidency immune from scrutiny.

The Nine, though, also displayed an interest in revisiting their own precedents. Justice Brett Kavanaugh fretted that this case could be “Morrison v. Olson Redux.” In that case, by a seven to one tally, the court upheld the office of the independent counsel as consistent with the Constitution. The lone dissenter was Justice Antonin Scalia, who declared that the ruling unlawfully infringed on presidential power. Justice Kavanaugh called the outcome “disastrous.”

Justice Samuel Alito pushed Mr. Dreeben about whether the conventional protections of the criminal law suffice to forestall political prosecutions of presidents. Justice Sonia Sotomayor declared that “there is no fail safe system of government, meaning, we have a judicial system that has layers and layers of protection for the accused in the hopes that the innocent will go free. We fail. Routinely. But we succeed more often than not.”