The Meaning of the Dreyfus Affair After October 7

A new biography appears with the Jewish state under attack and antisemitism on the rise.

‘Alfred Dreyfus: The Man at the Center of the Affair’

By Maurice Samuels

Yale University Press, 224 pages

The writer Solomon Rabinovich, known by his pen name of Sholem Aleichem, once observed that “Paris will not experience until Judgment Day” the “anguish and pain that Kasrileveke underwent” as a result of the Dreyfus Affair. That a fictional shtetl could undergo convulsions expected of the eschaton because of the fate of an artillery officer in the French army underscores that Dreyfus’s fate is, in another age of war against the Jews, a warning.

This new biography, from Maurice Samuels of Yale, restores Dreyfus to the ranks of Jewish heroes. Born in 1859 to a wealthy family of Alsatian extraction, he was a French patriot through and through. He was trained at the country’s finest military academies, where he excelled enough to secure a position on the French Army’s General Staff. There he was falsely accused of treason and banished for five years to a hellish existence on Devil’s Island.

While Dreyfus struggled to survive under conditions that Mr. Samuels sees as cruelly anticipatory of the Nazi concentration camps to come, his verdict came to grip first French Jews, then the Republic, then the world. It was a frame up, clumsily done, driven by antisemitism, that escalated into a crisis about liberal democracy, the fate of the Jews in modernity, and the future of France’s tattered Enlightenment dream.

Dreyfus is sometimes presented as a cautionary tale of the assimilated Jew — one contemporary newspaper editor called the French Revolution “our second Sinai” — but Mr. Samuels is adamant that “Neither Dreyfus nor his family sought to disavow their Jewish origins” despite French Jews having, at the time of his birth, been “the best integrated in the world.” Even when faced with starvation, he refused lard. He gave to Jewish causes.

“The Man at the Center of the Affair” underscores just what an excellent man Dreyfus was. He was Job transported to the Third French Republic. From the depths of his despair, he wrote that he “did not have the right to abandon or voluntarily desert my post.” His letters, written from what Mr. Samules describes as a “unique regime of total isolation, are replete with the word devoir, or “duty.” As an older man, he reported to the front in World War I.

Dreyfus’s two convictions and eventual pardon cleaved French society in two, especially the salons at its summit. The Dreyfusards counted in their ranks Émile Zola, Anatole France, Marcel Proust, and Claude Monet. Anti-Dreyfusards numbered Auguste Rodin, Pierre-August Renoir, Edgar Degas, and Paul Valéry. The motto of Dreyfus’s foes was “French for the French.” Alternative slogans included “Death to the Jews” and “Death to the Yids.”

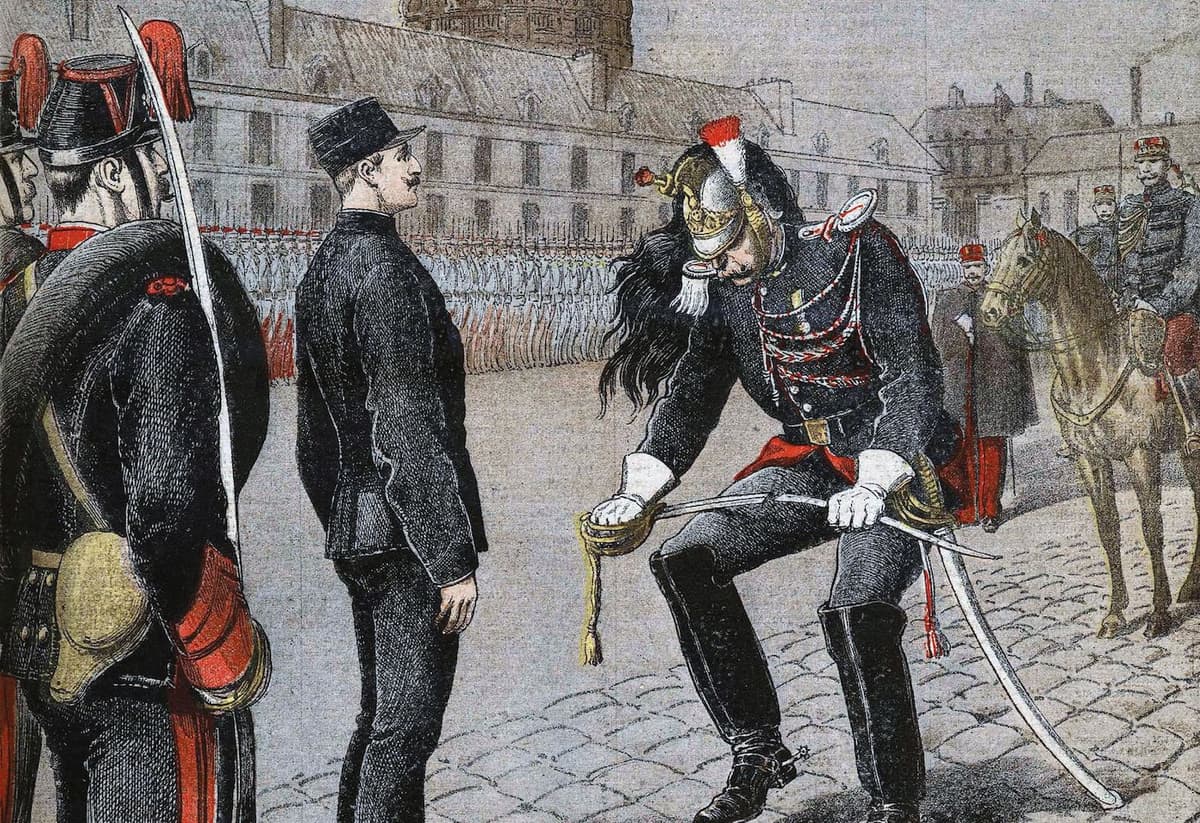

A correspondent, Theodor Herzl, for Vienna’s Neue Freie Presse covered Dreyfus’ degradation in 1895. He would have seen the soldier’s sword broken in two and his epaulets ripped off. Years later, he would declare in an unpublished essay that “what made me a Zionist was the Dreyfus trial.” That, though, was only after the affair had electrified France. Mr. Samuels allows that the affair “played a transformational role in the development of Zionism.”

The scholar Rick Richman writes in his “And None Shall Make Them Afraid” that “in the four volumes and 1,631 pages of his Zionist diaries, covering the nine-year period from 1895 to 1904, there are only 12 brief mentions of Dreyfus, none suggesting that the case played any role in Herzl’s conversion to Zionism.” The imbroglio, though, cemented for many that the Jews’ place in Europe was out of it. Others turned to socialism with renewed zeal.

The philosopher Hannah Arendt, writing in “The Origins of Totalitarianism” in 1951, called the Affair the “dress rehearsal for the performance of our time,” meaning the Holocaust. Not everyone at the same thought so — one Jewish journalist suggested that Dreyfus be subjected to the “pitiless penal code of Moses” — death by stoning — with the first stone to be hurled by France’s Chief Rabbi. More clear-eyed was another Zionist, Max Nordau.

The Dreyfus Affair not only dominated conversation at Kasrilevke. A dispatch from the future editor, Abraham Cahan, of the Forverts — whose rise Mr. Samuels attributes to its pro-Dreyfus position — reported from the Lower East Side that the “names of every actor in the Dreyfus case, from the unhappy prisoner of Devil’s Island himself down to the assistant of the lawyers on either side, are well known, therefore, to every cheder boy in the ghetto.”

Just as the perverse logic of antisemitism mandates that Israel is blamed for the atrocities committed against it, so too the appalling wrong done to Dreyfus hardened the hearts of those who saw him as a traitor. It was Dreyfus himself who was betrayed. In another world, one of Herzl’s dreams, this unrequited lover of France would have been a great general of Zion like Joseph Trumpledor, the hero of Tel Hai, or Moshe Dayan, the liberator of Jerusalem.