A Poet’s Legacy in Stone: Will Yeats’s Tower Survive?

The material legacy of the Nobel Prize winner now rests with a band of volunteers fighting the earth and the elements.

BALLYLEE, County Galway — They worry over the water, the women who watch that William Butler Yeats’s tower, Thoor Ballylee, doesn’t sink into the ground. The wet stuff comes in buckets in the winter, irrigating the grass to an emerald green and lending this corner of County Galway a soggy splendor. If Dublin is haunted by James Joyce, this rural redoubt is animated by Yeats, from whose pen flowed the old Celtic magic of grove and glen.

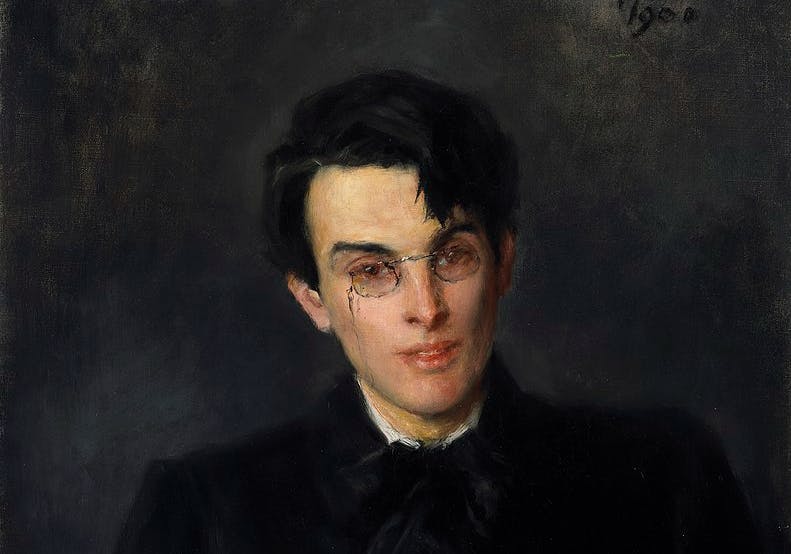

Keeping this pile of stone upright falls to a handful of volunteers, the Yeats Thoor Ballylee Society. I spent a day with one of them, Rena McAllen, to understand what a poet can mean to a people, and to clock the legwork and elbow grease required to keep memory alive. “Mad Ireland hurt you into poetry,” Wystan Auden writes in his elegy to Yeats, adding that “your gift survived it all.” The survival of this Celtic citadel, though, is no mere metaphor.

Ms. McAllen hails from Kiltartan, a parish minutes away from Thoor Ballylee. She tells me that her father, working the fields, would see Yeats strolling the rural roads, reciting poetry to himself with hardly a glance at those working the land he extolled in verse. She traces her family tree back to the O’Shaughnessy clan, a tribe whose medieval seat was at the small city of Gort. She is a keeper of the world that raised her.

Yeats bought the tower, a Hiberno-Norman fortress that dates to the 15th century, in 1916, the same year as the Easter Rising against the English. He and his wife Georgina, or “George,” summered there between 1921 and 1929, wrangling into domesticity this monument built by the successors to William the Conqueror. Yeats’s fellow Nobel prize winner, Seamus Heaney, called it “the most important public building in Ireland.”

This was no unlettered terrain, though. At the nearby Coole estate, a remarkable aristocrat, Lady Augusta Gregory, brought together at her high house Yeats, his brother, the painter Jack B. Yeats, the playwrights J.M. Synge, George Bernard Shaw, and others — their autographs are still visible, carved into the bark of a tree that has outlasted the vanished manse. Here, the Irish Literary Revival of the early 20th century flowered, and the Abbey Theatre was born.

Yeats wrote at Thoor Ballylee, but also about it, as when he declared, “I pace upon the battlements and stare / On the foundations of a house, or where / Tree, like a sooty finger, starts from the earth; And send imagination forth.” Two of his collections of poems, “The Tower” and “The Winding Stair,” took their titles from the demesne. If books need champions, towers need superintendents, and Thoor Ballylee fell into decrepitude for want of a caretaker.

As we climb the tower’s slippery staircase, Ms. McAllen tells me how she used to dart around the ruins of this tower as a child. Now, funds flow — not enough, is my sense — from the country’s tourism board, Fáilte Ireland, though the work is done by Ms. McAllen and her crew. A stone bench in the courtyard, donated by the doughty Kiltartian, is inscribed with Yeats’s maxim that “to go elsewhere is to leave beauty behind.”

Others were more skeptical, with the poet Ezra Pound declaring it a “phallic symbol on the bogs – Ballyhallus or whatever he calls it with the river on the first floor.” Yeats, though, reveled in imagining its previous occupants, “rough men-at-arms, cross-gartered to the knees,” who likely preferred swordplay to wordplay. Now, though, Ms. McAllen and her camarilla worry about bats in the rafters and weigh the merits of industrial-strength dehumidifiers.

More moving even than the stone keep of Thoor Ballylee, at least to this correspondent, was the Kiltartan Gregory Museum, a former schoolhouse — Ms. McAllen points to where she once sat — that has found new life as a repository of local memory. A nun, Sister de Lourdes Fahy, has spent her years tracing the parish’s genealogy, its family trees sustained by tradition and felled by famine. She, no less than Yeats, or Norman stone, holds the history of this place.