Gorsuch Alone Against Caesar

This article is from the archive of The New York Sun before the launch of its new website in 2022. The Sun has neither altered nor updated such articles but will seek to correct any errors, mis-categorizations or other problems introduced during transfer.

A Presbyterian church in Virginia will have to render more “unto Caesar” and less “unto God” following a defeat in a property tax dispute today at the United States Supreme Court. The church had sought to avoid paying property taxes on a residence used by two of its staff members, whom it considers to be ministers. Under Virginia law, ministers’ residences are exempt from local property taxes. Yet the city of Fredericksburg doubted the staffers were actually ministers.

The Nine declined to take up the dispute, saddling the Virginia church with the tax bill. In a dissent, Justice Gorsuch took exception to the notion of government officials interrogating churches over how they classify their personnel: “Bureaucratic efforts to ‘subject’ religious beliefs to ‘verification’ have no place in a free country,” he wrote. “This case may be a small one,” he says, and he hoped it was “unlikely to be repeated anytime soon.”

Yet the question of whether an employee qualifies as a minister isn’t limited to property tax disputes. Religious groups, including schools, have also cited the so-called “ministerial exception” as grounds for remaining unfettered by state and federal rules relating to hiring and firing. In 2012, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously that this exception gives religious groups broad leeway over selecting their ministers. It also enjoins ministers from filing employment discrimination suits against their employers.

In that case, Hosanna-Tabor Evangelical Lutheran Church and School v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, Chief Justice Roberts noted the Michigan church school’s distinction between “called,” or ministerial, and “lay” teachers. After a “called” teacher fell ill and was fired, she accused the church of discrimination, citing the Americans with Disabilities Act. The teacher initially sought to be rehired, then demanded damages instead. The Supreme Court found the church was within its rights to fire her.

The First Amendment’s “Religion Clauses,” Chief Justice Roberts explained, “bar the government from interfering with the decision of a religious group to fire one of its ministers.” That’s because “members of a religious group put their faith in the hands of their ministers,” Chief Justice Roberts explained. “Requiring a church to accept or retain an unwanted minister, or punishing a church for failing to do so, intrudes upon more than a mere employment decision.”

While the Supreme Court has granted religious groups wide discretion over hiring and firing of ministerial staff, the high court has not clearly defined which employees are ministers. “We are reluctant,” Chief Justice Roberts said, “to adopt a rigid formula for deciding when an employee qualifies as a minister.” That has opened the door to litigation in cases where, say, Roman Catholic schools sought First Amendment protection in firing teachers who are gay.

In the Virginia church case, the employees in question were “Directors of College Outreach and Youth Ministers,” the church says, “ministering to students” at a nearby university. Fredericksburg objected that they were only employed part-time. The city “conducted extensive discovery into church practices and beliefs,” Justice Gorsuch noted. City officials even asked whether the church was permitted to ordain one of the female ministers in light of her being a woman.

“Absent proof of insincerity or fraud,” Justice Gorsuch contends, “governmental intrusions into ecclesiastical questions are ‘impermissible.’” Yet Fredericksburg “continues to insist that a church’s religious rules are ‘subject to verification’ by government officials,” he writes. This clearly riles the justice. He notes that the Founders “were acutely aware how governments in Europe had sought to control and manipulate religious practices and churches,” and had vowed not to repeat that in the new nation.

Citing James Madison’s “Memorial and Remonstrance,” which argues for keeping government out of religious affairs, Justice Gorsuch notes that in the Founders’ vision, America “would not subscribe to the ‘arrogant pretension’” that government officials can act as judges “of Religious truth.” In Justice Gorsuch’s view, “religious persons” should “decide for themselves, free from state interference,” the vital questions of “faith and doctrine.” Hence his dissent where, for now, Caesar won the day.

_________________

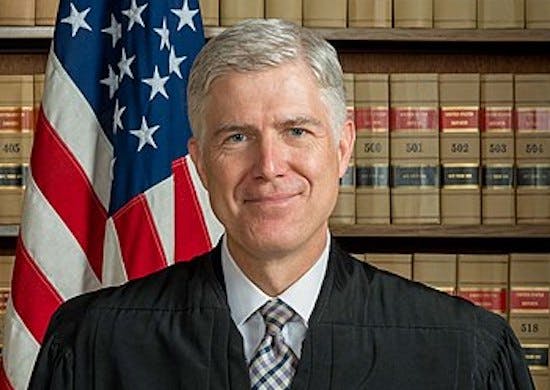

Image: Detail of official portrait of Justice Gorsuch, via Wikimedia Commons.