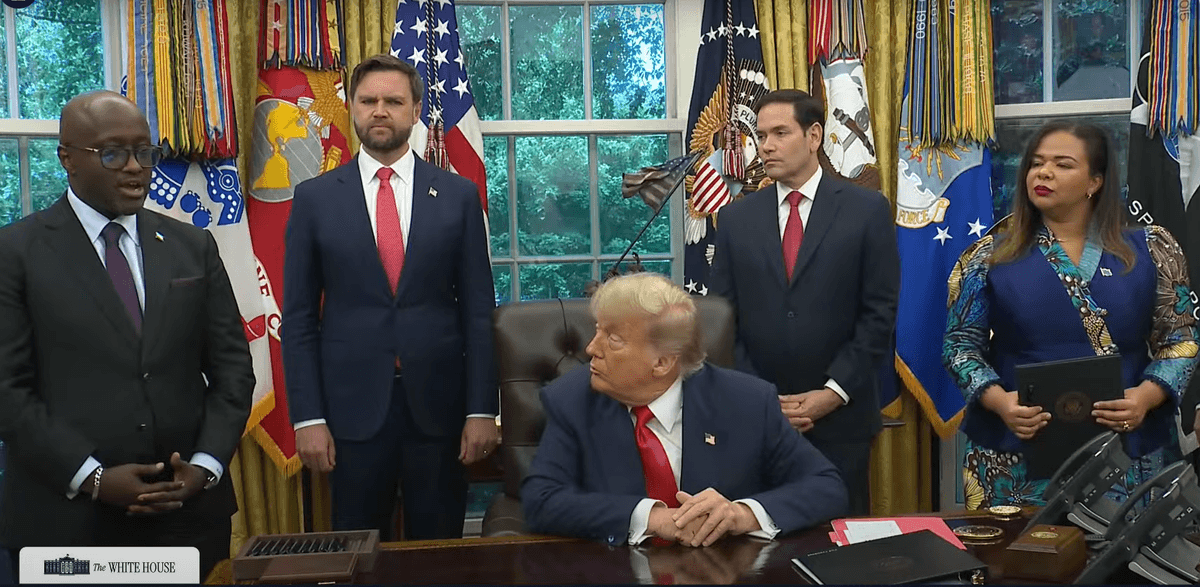

Pay to Play? Nations Spend Big on K Street To Get Trump’s Attention

Spending on Washington lobbyists by foreign governments accelerates in the first months of the president’s term, raising concerns about whether America is ‘first’ or for sale.

Foreign governments have sharply escalated their spending on lobbyists since President Trump’s return to the Oval Office, cementing Washington’s famed K Street as a global playground of insider influence.

In the first quarter of Mr. Trump’s second term, the top 10 lobbying firms in Washington saw revenues surge to approximately $123 million compared to about $80 million during equivalent periods under President Biden and Mr. Trump’s first term.

Individual firms recorded striking gains—Ballard Partners, whose chief Brian Ballard, is closely tied to President Trump, jumped by roughly 225 percent to $14 million, while Washington mainstay Akin increased 18.75 percent to $16.4 million. Broader federal lobbying spending reached a record $4.53 billion in 2024, up from $4.35 billion in 2023, marking real growth beyond inflation.

“The ‘America First’ rhetoric is spawning a wave of foreign intervention in American policies, and the lobbyists with inside connections to Trump are cashing in,” a government affairs lobbyist for the nonprofit consumer advocacy organization Public Citizen, Craig Holman, tells the New York Sun.

Early evidence shows that several countries have sharply increased their lobbying outlays in Washington since the start of President Trump’s second term. The Democratic Republic of the Congo, for example, renewed a $100,000-per-month contract with Ballard Partners in 2025, roughly $1.2 million annually, more than double the $553,500 it reported in 2023.

Somalia signed a $600,000 retainer in late 2024, entering 2025 at spending levels not seen since its $676,646 in 2018. Amid trade tensions, Pakistan hired seven different firms to influence American foreign policy. Countries with smaller GDPs like Haiti, Mozambique, Rwanda, and the Philippines are collectively spending more than $21 million through 2025 on lobbying fees.

In January, Angola signed a $312,500-per-month contract with Squire Patton Boggs, its long-time lobbyist, totaling nearly $3.8 million annually. The nation signed a separate contract in February with BGR Government Affairs worth $2.04 million annually. BGR also represents Panama for $2.46 million per year. Both companies have deep ties to Mr. Trump.

Qatar, which in May promised investment in America of $500 billion over the next decade plus $1.2 trillion in economic exchanges, has increased its representation in Washington as well, paying $210,000 over seven months to try to dispel the notion that American universities in Qatar are indoctrinating students in study-abroad programs with Islamist curricula.

The trends show that strategically positioned or aid-dependent nations are increasingly investing in Trump-linked lobbying firms to gain political and economic leverage.

The surge is to be expected. The president’s style of diplomacy is highly transactional, with a clear message to allies and adversaries that American support is not guaranteed but earned. That approach has made lobbying in Washington less of a luxury for foreign governments and more of a necessity, as they seek to demonstrate loyalty and secure favorable terms.

Mr. Trump’s governing style also places weight on personal relationships. That emphasis has made lobbyists with connections to his family, business associates, and political allies especially valuable. Firms with proximity to Mr. Trump and his inner circle have been able to command record-breaking fees from foreign clients eager for access.

Revival of tariffs as a core economic policy has also forced industries and governments to scramble for exceptions. When Mr. Trump imposed sweeping tariffs on steel, aluminum, and other goods this year, dozens of nations hired Washington representation—fueling a lobbying boom as countries seek to shield their exporters from costly trade barriers or instability.

“Trump’s threats of tariffs, seizing foreign lands, and deportations of immigrants and other policy positions have prompted a surge in foreign countries lobbying the United States,” says Mr. Holman.

At least 154 nations and territories currently have registered lobbyists operating on their behalf in Washington. While lobbying gets a bad rap because of the fine line between democratic representation and influence peddling, it is also a protected activity. The First Amendment guarantees the right “to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.” This guarantee extends to individuals, corporations, unions, and even foreign governments, though such actions are regulated by federal laws.

Lobbying is critical in several ways. It provides policymakers with expertise and information they might otherwise lack, while giving citizens and interest groups a direct line to lawmakers. It is how the steel industry explains its needs during a tariff fight, how a small country defends its aid package, and how veterans’ groups make sure their voices are heard.

However, watchdogs stress that the problem is not merely money—it’s the concentration of access among big spenders who may be working at cross-purposes with the American public.

Foreign nations “often push U.S. foreign policy in militarized directions, including promoting arms sales, expanding U.S. military bases abroad, and even pulling the U.S. directly into foreign conflicts,” said the director of the Democratizing Foreign Policy program at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, Benjamin Freeman.

“Meanwhile, the average American has grown extremely weary of American involvement in foreign wars and generally prefers a much more diplomatic approach to U.S. engagement with the world,” Mr. Freeman continued. “So, we often see a big disconnect between what Americans actually want their country’s foreign policy to look like and what foreign lobbyists are pushing for.”

He added that the outlay of significant sums to American firms may not be in the best interests of the nations ponying up. As the latest reports show, lobbyists are often hired by some of the world’s poorest nations, often seeking trade concessions, access to minerals, or military support even if it drains resources better spent on domestic issues. At the same time, their efforts may be outsized by countries with much larger budgets.

“While some foreign lobbying can improve global diplomacy by ensuring foreign voices are heard in Washington, the volume of those voices is dramatically unequal as some countries spend far more than others,” said Mr. Freeman.

Transparency is one key to making sure that lobbyists don’t undermine the will of the American people. The Foreign Agents Registration Act was enacted in 1938 with the idea that the sunlight of registration and disclosure would keep corruption at bay.

But with the surge in foreign lobbying, some analysts say stricter FARA enforcement is needed, along with spending caps and stronger disclosure rules to prevent foreign money from outweighing voter priorities.

“The Foreign Agents Registration Act was designed to capture this activity, but it hasn’t been meaningfully updated since the mid-1990s,” director of government affairs at the Project on Government Oversight, Dylan Hedtler-Gaudette, tells the Sun.

“There have been some minor tweaks, but we’re in a very different world now than we were then. The regulatory and legislative framework around foreign lobbying needs updating.”

Mr. Hedtler-Gaudette said one significant gap is the lobbying disclosure act exemption.

“It allows a foreign agent to register under the Lobbying Disclosure Act instead of FARA. The LDA is primarily designed for domestic lobbying, so foreign agents who register under it are subject to less stringent reporting and disclosure requirements,” he argued. “It’s a loophole that reduces oversight and transparency.”

For Mr. Trump supporters, the focus is pragmatic: if spending by countries like Saudi Arabia or Poland advances American strategic interests, it aligns with an America First agenda.

Foreign lobbying is not new, but its scale under Mr. Trump’s leadership has made it more visible than ever. And that may last beyond his administration.

“Once an entity joins the fray of lobbying, they tend to stay in the game even after an immediate objective is achieved,” Mr. Homan said. “They see the value that can come from lobbying inside the Beltway, so I suspect many of these new foreign registrants will continue lobbying even after Trump has left office.”