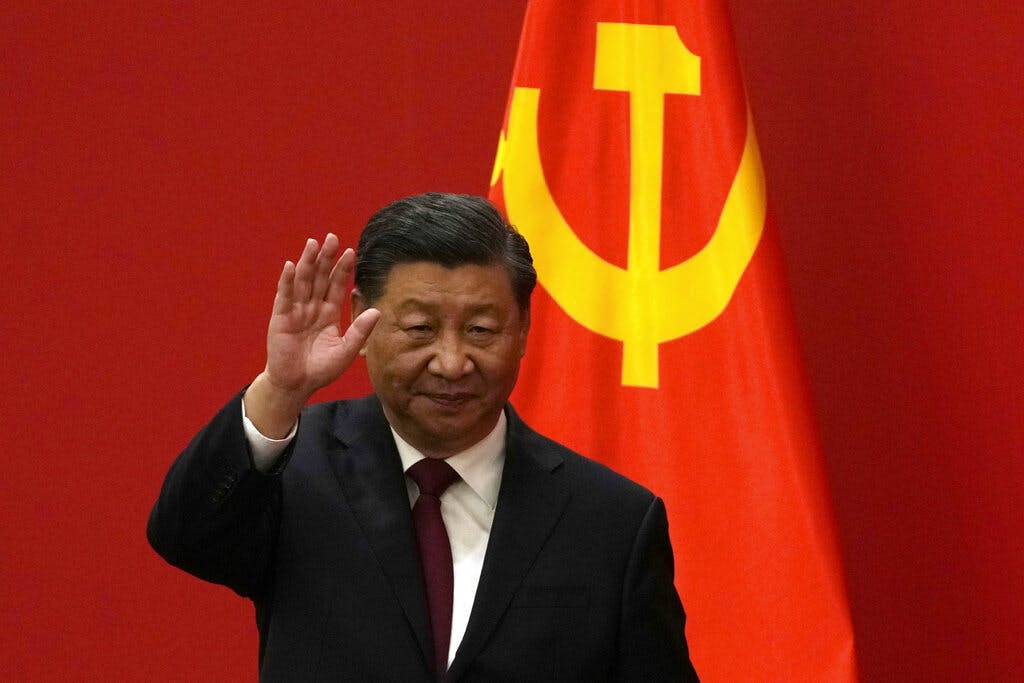

President Xi Embraces the Private Sector

Is Communist China coming to grips with the implications of stifling free enterprise?

President Xi’s about-face, embracing Communist China’s sidelined private sector, could be good news for the Mainland’s economy and its high-tech sector. Yet China has a long way to go before private enterprise can get out from under state control. China, after all, has in recent years hurt its own growth via Mr. Xi’s “brutal regulatory moves,” which “hammered profits” and “wiped out some businesses,” Bloomberg says, in the name of bolstering state power.

Some five years after launching that crackdown, is Mr. Xi now coming to grips with the implications of stifling private enterprise? That’s what some are suggesting in light of Mr. Xi’s meeting today with the co-founder of the e-commerce giant Alibaba, Jack Ma, and other top tech entrepreneurs. Mr. Ma had largely disappeared from public view after he made a speech in 2020 criticizing the heavy hand of Mr. Xi’s communist regime.

Mr. Ma’s dissent fueled Mr. Xi’s aim of reverting to Communist China’s roots in Maoist statism. As a result, Cornell’s Eswar Prasad explains, Mr. Xi “prioritized state enterprises, which hew closely to the Chinese Communist Party line and are under direct government control, over the private sector.” Successful tech firms that grew “too big and powerful” were broken into “smaller units and are now subject to more state control,” Mr. Prasad explains.

Today’s event suggests that Mr. Ma was back in the regime’s good graces and conveys “Beijing’s endorsement for a long-marginalized private sector now considered key to reviving the world’s No. 2 economy,” Bloomberg reported. Mr. Xi’s calculus, it seems, is that China will need a resurgent tech sector amid “the domestic economy slowing and geopolitical pressures escalating,” says the University of Southern California’s Angela Huyue Zhang.

More broadly, Beijing is grappling with how to get China’s economy moving faster again. After strict Covid restrictions ended in 2022, the expectations were for a rapid recovery. Instead, CNN reports, “the economy has floundered, weighed down by its ailing property sector and low consumer confidence.” At the same time, China’s debt burden is “a financial time bomb that could severely damage its banking system,” the Wall Street Journal reports.

The challenges reflect Mr. Xi’s choice to double down on central planning, rather than letting the free market decide how to invest resources. As a result, China’s economy is “burdened with excess,” the Journal says, with “millions of empty or unfinished apartment blocks, trillions of dollars in debt straining local governments and ballooning industrial production driving an export surge that is igniting trade tensions worldwide.”

All of these problems stem from the absence of freedom under China’s dictatorship. As these columns have put it, “the problem isn’t with the Chinese economy, it’s with communism.” In the long run, economic prosperity is not compatible with tyranny. “Economic liberty and political liberty are the warp and woof of the fabric of freedom and it is not possible to have economic liberty without political liberty,” is how the Sun has put it.

That outlook was bolstered when, starting in 1979, Mr. Xi’s predecessor, Deng Xiaoping, started lifting repressive Maoist-era restrictions on Chinese economic activity. The result was a kind of economic miracle: Some three decades of 10 percent annual growth. Leading the way in that regard were the “Special Economic Zones” in China’s southeastern coast, which have long been the nation’s most outward-looking regions.

Indeed, Zhongsan, near Hong Kong, is where Chinese democracy’s pioneer, Sun Yat-sen, the first president of the Chinese republic, was born. A New York Sun correspondent, Sun was the product of “an extended China exposed to cosmopolitan influences,” his biographer, Marie-Claire Bergère, wrote. If the mandarins want to revive growth, they would do well to embrace Sun’s vision of self-determination, including economic freedom.