The Logic of Grand Jury Secrecy — Even in Epstein Cases

Secrecy of the grand jury evidence lies, in the Epstein cases as others, at the core of one of the most important rights vouchsafed in the Constitution.

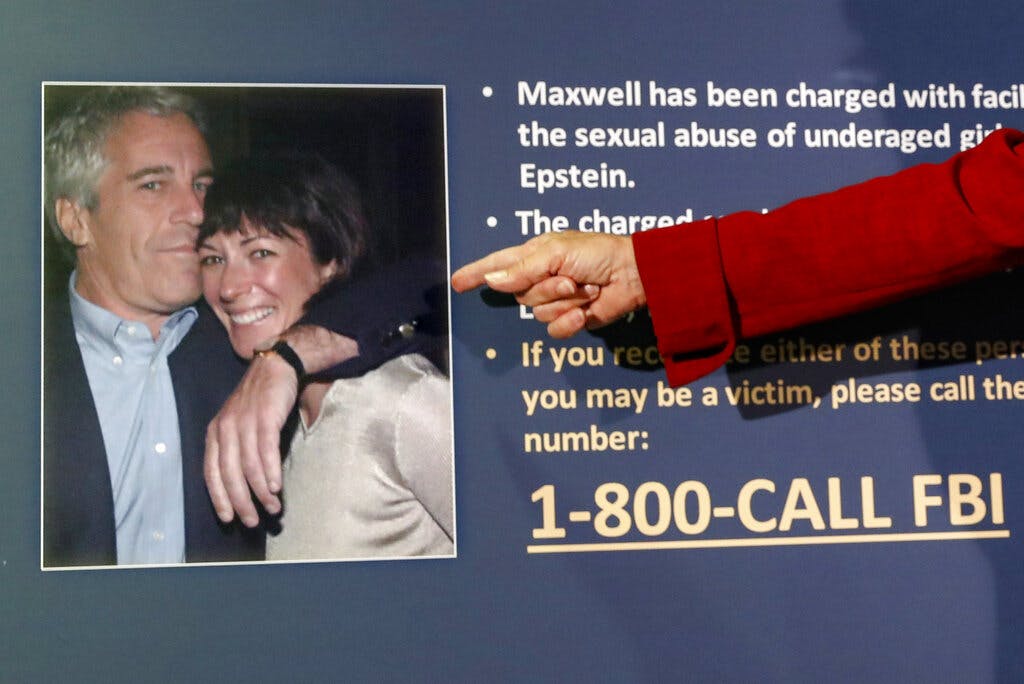

President Trump’s push to release federal grand jury transcripts in the cases of Jeffrey Epstein and his convicted procuress, Ghislaine Maxwell, is being touted as a way to assuage public interest in the prosecutions. That’s a matter of political expediency, though, and it raises a constitutional red flag by breaching the secrecy of grand jury deliberations. A grand jury, after all, is one of the bedrock rights protected in the Bill of Rights, and secrecy is key to that right.

Mr. Trump’s Department of Justice says that its request to open up the records of the grand jury proceedings “is consistent with increasing calls for additional disclosures in this matter.” In a court filing, the DOJ calls its request “a preliminary indication that the need for secrecy is not especially strong.” That’s a curious conclusion, though, in light of the long history favoring a policy of secrecy for the investigative work undertaken by grand juries.

That’s a point marked in the Sun’s pages during an earlier call to open up grand jury records. In 2014, a grand jury at Staten Island declined to hand up an indictment of a police officer, Daniel Pantaleo, in the case of a criminal suspect, Eric Garner, who died after the officer had placed him in a chokehold. After a public uproar, New York’s chief judge, Jonathan Lippman, sought to make public grand jury testimony in the case of Garner’s death.

Yet “all kinds of reasons exist for grand juries to conduct their deliberations in secret,” we have marked in these columns. “This is so fundamental that it has existed in English law for centuries and is required by New York state law.” The secrecy helps to prevent “tampering” with the grand jury’s investigation, Judge Lippman himself conceded. It also helps to deter gossip, while serving to “encourage reluctant witnesses to cooperate,” he added.

Secrecy, too, helps to protect the innocent from unjust prosecutions — despite the tendency of grand juries to prove amenable to handing up indictments. That propensity led to the famous quip by another former chief judge of New York, Sol Wachtler, that “any good prosecutor can get a grand jury to indict a ham sandwich.” That said, though, the case of Officer Pantaleo is an exception that underscores the value of hewing to the constitutional niceties.

Viewed through that lens, Judge Lippman’s push to void grand jury secrecy in the Pantaleo case suggested that the judge “wants to lift the figurative blindfold that symbolizes impartial justice and put a thumb on the scale that blind justice is supposed to be holding,” we have reckoned in these columns. More broadly, Judge Lippman even sought to end the tradition of secrecy in all cases involving police officers accused of harming civilians.

Is that attempt to insert politics into the constitutional right to a grand jury any less egregious than the push to publicize the Epstein transcripts? No one wants to overlook the sordid nature of the accusations against Epstein and Ms. Maxwell. Yet the Fifth Amendment’s guarantee that “No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury” does not make for such exceptions.

A federal judge in Florida’s southern district, Robin Rosenberg, said that her “hands are tied” on the question of releasing the transcripts in the Epstein case. Federal criminal procedure rules stress “a presumption of secrecy,” she explains. Plus, too, federal law in the 11th Circuit “does not permit this Court to grant the Government’s request.” A federal judge at New York is, in Ms. Maxwell’s case, still weighing the government’s request.

Judge Paul Engelmayer of New York’s Southern District explains in his response to the DOJ that the principle of grand jury secrecy is “older than our Nation itself,” making the request one of the “most sensitive exercises of careful judgement that a trial judge can make.” For both these jurists, as well as whichever higher courts take up this question, it is hard to see how the release of the transcripts in the Epstein and Maxwell cases can be squared with the Constitution.