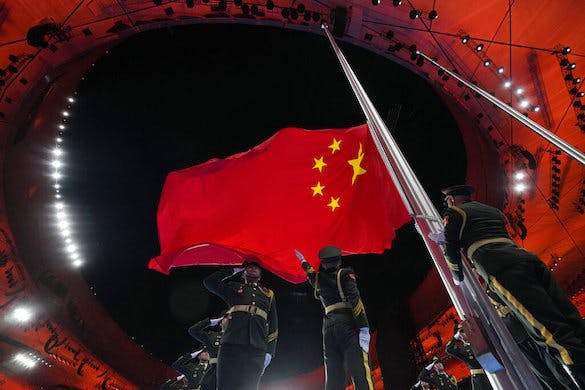

American, Japanese Forces Play Hyped-up ‘Iron Fist’ War Games Against Constant Threat of Communist Chinese Invasion of Taiwan

By DONALD KIRK

|The Soviet Union collapsed three decades ago, and America has yet to fully adjust.

Already have a subscription? Sign in to continue reading

By DONALD KIRK

|

By LUKE FUNK

|

$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

By continuing you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.

By BRADLEY CORTRIGHT

|