The State of Joe Biden

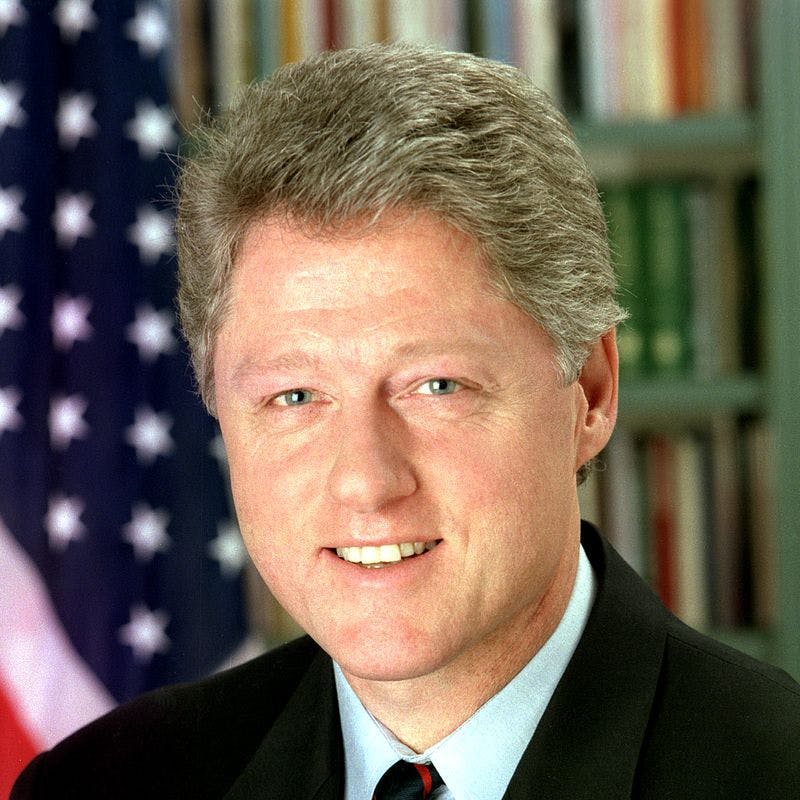

Historians of the presidency point to Mr. Biden’s opportunity on Tuesday to recast the narrative of his administration. President Clinton’s 1995 address offers a parallel.

It’s hard to recall a drama quite like that which will go up in the Congress tonight, when President Biden delivers his first State of the Union message. It will feature a president who racked up the largest vote total in history making his debut before a Congress that has rejected his defining domestic proposal, the $5 trillion dollar scheme called Build Back Better, and a world wondering whether he can get off defense.

Even while Mr. Biden has been tested at home — unable to unite his own caucus in an evenly divided Senate — the world is witnessing the consequences of weakness and appeasement abroad. It would be inaccurate to suggest that Mr. Biden is the villain in respect of Afghanistan, Ukraine, Iran, or Communist China. The villains are the Taliban, President Putin, the regime in Tehran, and the Chinese communist party.

It would not be off key, though, to suggest that Mr. Biden has failed in leadership on these fronts. His bid to put through a $5 trillion spending plan at a time of low unemployment and inflation is reckless (and well marked as such by our Larry Kudlow). The surrender of Afghanistan is one of the worst errors in American history, ranking right up there with, say, Congress’s cut off in 1975 of aid to Free Vietnam.

Mr. Biden’s blunders complicate his path forward. Yet historians of the presidency point to Mr. Biden’s opportunity on Tuesday to recast the narrative of his administration, as in, say, the case of President Kennedy. In 1961, following another foreign policy debacle, the Bay of Pigs invasion, JFK, recalls Michael Beschloss, sought to “turn the page” with a speech to Congress in which he pledged to send a man to the moon.

Kennedy’s speech was meant to “give a second wind to his administration,” Mr. Beschloss observes, “which it did.” Mr. Biden isn’t expected to propose anything so bold on Tuesday, even if the need for a course correction is as acute. The more apt parallel for Mr. Biden’s speech writers is President Clinton’s 1995 address. It proved to be a turning point, laying out the triangulation strategy that put him on a path to re-election.

Like Mr. Biden today, Mr. Clinton in early 1995 was buffeted by adverse political headwinds. As with Mr. Biden’s spending plan, an overambitious proposal — Hillary Clinton’s health care overhaul — had failed in congress and provoked a political backlash. Tax increases and gun control energized opposition. Propelled by the success of the “Contract with America,” Republicans in the midterms had won control of Congress.

Yet as Clinton adviser Donald Baer observes, when Mr. Clinton began his speech, he appeared “anything but unprepared or a downtrodden political victim.” He deployed humor, conceding in the midterms “we didn’t hear America singing, we heard America shouting.” He spoke of deficit cuts, ending welfare, and getting “tougher on crime.” The strategy, Mr. Bear says, was for the president to move to “a position above and beyond the fray.”

By setting a new course between the far left of his own party, as well as the more zealous proposals from Speaker Gingrich and a rising generation of rightwing Republicans, Mr. Clinton’s speech showed that he could “provide leadership reaching beyond the old boundaries of left and right,” Mr. Baer says. Mr. Clinton went on to follow his own path and “become the first Democratic president in 60 years to win a second term.”

Some 27 years later, Mr. Biden’s challenge is deepened by the fact that, unlike Mr. Clinton, many of his political problems are centered on foreign policy woes that cannot be easily resolved by Mr. Clinton’s tactic of triangulation. Mr. Biden, at age 79, would be hard pressed to position himself as “a different kind of Democrat.” Then again, too, Mr. Biden hasn’t — as yet — lost control of the Congress.

All the more reason for Mr. Biden to try to turn things around. Even so, his speech is unlikely to have the magic of JFK’s call to send a man to the moon. It is also far from clear whether Mr. Biden has the rhetorical chops, or the political instincts, to give the kind of speech that enabled Mr. Clinton to so dramatically reverse his political fortunes in 1995. Or that Mr. Biden has the will, or strength, to confront his party’s left wing.