Twilight of the Republics?

An American president fails to learn from history as a Houthi army working for Iran closes a major artery of global commerce, including that of Americans.

‘America lives in a world of her own . . . safe from attack, safe even from menace, she hears from afar the warning cries of European races and faiths, as the gods of Epicurus listened to the murmurs of the unhappy earth beneath their golden dwellings . . .’ —James Bryce, ‘The American Commonwealth,’ 1888

These words, penned by Victoria’s ambassador to Washington, are quoted in Robert Kagan’s history of the failures of American isolationism in the early 20th century, “The Ghost at the Feast.” Someone ought to send the book to President Biden, who is losing the Battle of the Red Sea. Mr. Kagan writes how foreign perils troubled the tranquility traced by Bryce, as a feckless Democratic president failed to confront our enemy’s threat to American ships.

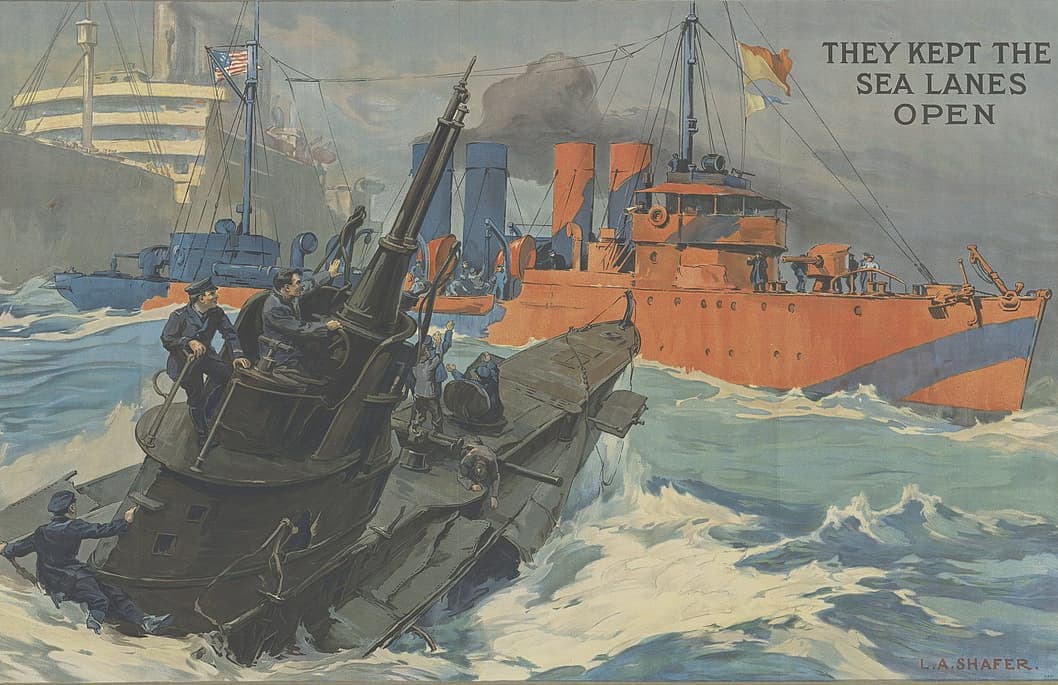

That threat, during World War I, was posed by the submarines of the German Empire, which were waging indiscriminate warfare on transatlantic shipping in an effort to cut off supplies to the Allied powers, Britain, France, and Russia, as war raged on the continent. Today, the theater is the Red Sea and the instigator the Islamic Republic of Iran, whose cats-paw, the Houthis, are waging a de facto war on naval commerce in a vital artery of world commerce.

The parallels are striking. In the leadup to World War I, Mr. Kagan explains, Americans kept aloof from Europe’s shifting alliances and rising tensions, in part because of the expectation that the British Navy would maintain peace in the Atlantic — and keep open the sea lanes for commerce. The outbreak of the war in the summer of 1914 did little to change these views, at first. “We definitely have to be neutral,” Wilson mumbled in September that year.

Editorials in William Randolph Hearst’s papers dismissed the conflict as a “war of kings” started by “homicidal maniacs.” Colonel Robert McCormick in 1914 mocked the pretensions of the monarchs who launched the war in an immortal editorial, “Twilight of the Kings.” The editorial excoriated these rulers for invoking divine aid for their murderous aims, concluding: “The republic marches east.” The war, Wilson said, “cannot touch us.”

Even so, America could not remain aloof from the war, in part because Germany embarked on a policy — a kind of forerunner of asymmetrical warfare — of deploying its small fleet of submarines to try to cut off the flow of American sea trade across the Atlantic. The Germans, Mr. Kagan says, “believed the Americans would not fight.” Berlin declared the waters around Britain a “war zone” in which even neutral nations’ ships would be sunk.

Despite these provocations, the escalating German aggression went unanswered by Wilson. In March 1915 a British ship was sunk, leading to an American death. Wilson was persuaded not even to condemn the action. “The next day,” Mr. Kagan writes, an American ship was bombed in the North Sea, and “again, Wilson did not react.” Instead he “looked to the British” for help and even sought to placate the Kaiser.

“Wilson’s passivity,” Mr. Kagan reckons, emboldened Germany, which ramped up its submarine war. This culminated in the May 1915 sinking of Royal Mail Ship Lusitania, killing 124 Americans. Even then, Wilson’s response was limited to a demand for “an apology and reparations,” Mr. Kagan writes. He also demanded an end to submarine warfare, Mr. Kagan observes — but dropped it after Germany failed to respond.

Instead, Mr. Kagan explains, Wilson asked the Germans to “follow the rules” of war at sea and said that further attacks affecting Americans “would be regarded as deliberately unfriendly.” It was clear, Mr. Kagan notes, that Wilson “very much wanted to avoid war.” It would be two more years before America entered the fight, following the 1916 election, which Wilson won with the motto “he kept us out of war.”

This brings us back to the Red Sea, where Mr. Biden’s inadequate action in the face of Iran echoes Wilson’s refusal to grasp the German threat. It wasn’t until America’s entry into the Great War that, in Mr. Kagan’s account, America embraced responsibilities commensurate with its power. Mr. Biden’s weakness amounts to a regression, underscoring the danger of assuming that America’s geographic distance from threats leaves us “safe from attack.”