A Must-See Exhibition Is About To Land at the Met, ‘Caspar David Friedrich: The Soul of Nature’

Friedrich has been adopted as a poster boy by the environmentally minded after once being extolled as an exemplar of German art by none other than Adolph Hitler.

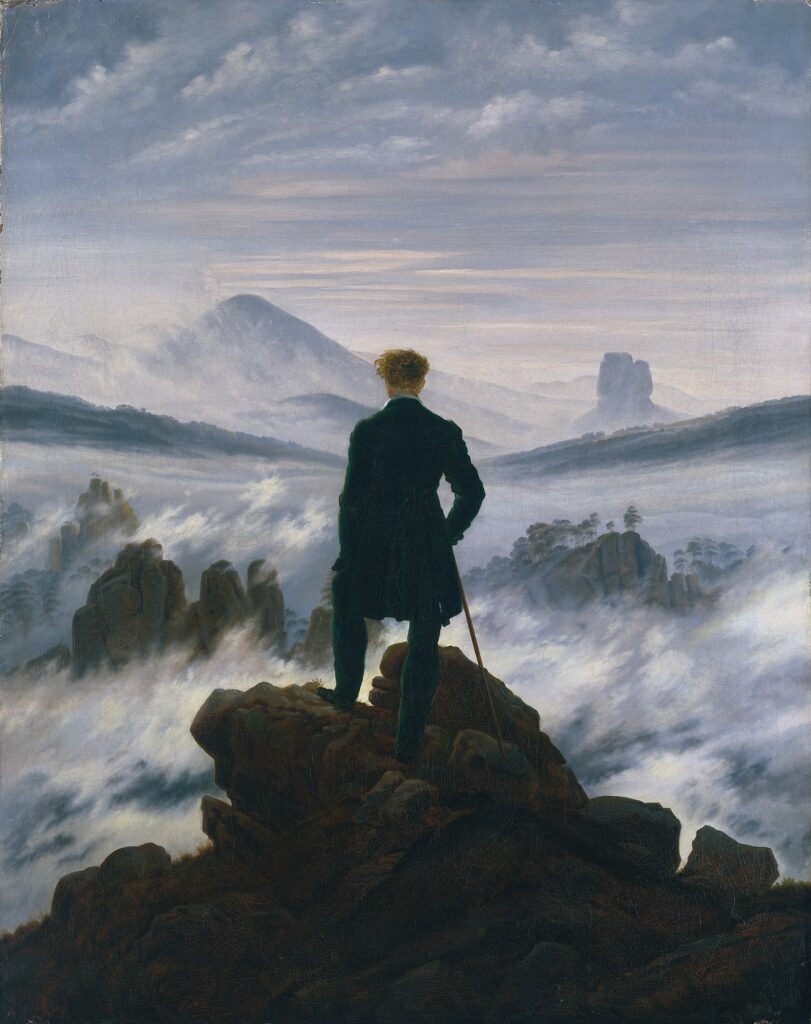

Caspar David Friedrich’s “Wanderer above the Sea of Fog” (circa 1817) is among the world’s most recognizable — please, let’s rest the tired word “iconic” — paintings. If the artist’s name or the title don’t ring a bell, rest assured: You know the image.

In it, we see a lone figure, dressed to the nines and with his back to the viewer, standing atop a rocky crag contemplating a boundless landscape. Although the picture might not have the cultural currency of “Girl With A Pearl Earring,” “Mona Lisa,” or the many iterations Frida Kahlo did on her unibrow, its purchase on popular taste is significant.

“Wanderer above the Sea of Fog” is hard to beat as an avatar of Romanticism, what with its heady conflagration of supernatural longing, adoration of the natural world, and I-Me-Mine individualism. When the vogue for Romanticism hit its sell-by date, Friedrich’s reputation suffered and he died in obscurity. A hundred years later, Friedrich was extolled as an exemplar of German art by Adolph Hitler — a distinction that put a brow-furrowing spin on the oeuvre.

Yet things change: Friedrich has since been adopted as a poster boy by the environmentally minded. To quote historian and scholar Stephanie O’Rourke, Friedrich’s vision is of “a natural world that has been drastically altered by human industry.”

Art of the past will forever be drafted into the service of theoretical fashion, and those doing the strong-arming often create a sea of fog denser than that seen in the Friedrich canvas. What is truly surprising, then, about an upcoming exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Caspar David Friedrich: The Soul of Nature,” is that it is the first retrospective of the work mounted in America. Organized in honor of the 250th anniversary of Friedrich’s birth, the Met has worked in cooperation with a triad of German museums — the Alte Nationalgalerie of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, and Hamburger Kunsthalle — to give us an exhibition that is, by dint of its rarity, a must-see.

Friedrich (1774-1840) was one of 10 children born to a father who made soap and candles, and a mother who died young: Sophia Dorothea passed away when Caspar was all of 7 years old. Death was a frequent visitor to the Friedrich home: Two sisters were lost to typhus and a younger brother perished by drowning. That Johann Christopher met his fate while trying to rescue Caspar from the icy depths of a lake adds a dramatic fillip to a life marked by trauma. It’s not much of a reach to conjecture how these tragedies might funnel their way into an artist’s vision.

Sixteen-year-old Caspar began his art studies close to home at the University of Greifswald and eventually attended the Academy of Copenhagen, at which the instructors advocated on behalf of a precursor of Romanticism, the advertised-as-is movement Sturm und Drang.

Upon settling at Dresden, Friedrich caught the eye of a poet, philosopher, and statesman, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, who wrote that the artist’s canvases combined “a great deal of firmness, diligence and neatness.” Goethe’s raves notwithstanding, Friedrich had a bumpy career. He ran afoul of political and public tensions, and died of an unknown malady that had, from all reports, accentuated an already existing strain of paranoia.

“Wanderer above the Sea of Fog” is on display at the Met — New Yorkers will be taken aback, I think, by its modest size — along with three-dozen or so additional canvases, preparatory studies rendered in graphite and watercolor, and select works done by friends and peers. The influence of 17th-century Dutch landscape painting is unmistakable — Friedrich encountered examples of the genre as a student in Denmark — as is a fealty to the geographical distinctiveness of light and atmosphere. His cool, keening tones are closely observed and seemingly eternal: The skies in Friedrich’s pictures can still be experienced when traveling through 21st-century Germany.

Naturalism had its limits: “a picture should not simulate nature itself and attempt to deceive, but should only remind one of it.” In that regard, Friedrich’s reminders tend toward a brittle nostalgia, to an Arcadian impulse peppered with a dark strain of sentimentality. When working on paper, and especially with brown ink and wash, he achieved a clarity reminiscent of the lyrical sonorites found in Asian art. “Eastern Coast of Rügen with Shepherd” (1805–6), with its yawning sense of space, is a miracle of luminosity, while “Cave in the Harz” (circa 1837) is an eye-bending exercise in illusionism.

When putting oil to canvas, Friedrich’s spiritualist impulses often capitulated to a fiddly sense of finish and cloying hazes of saturated colors. His handling of shape, volume, and texture can be eccentric, as in “The Watzmann” (1824-25), in which a range of mountains is transformed into a magisterial setting dramatically devoid of air. The finest of the paintings, “Monk by the Sea” (1808-10), is a bravura display of moody affect achieved through the slimmest of means. Elsewhere, Friedrich proves an iffier artist, reliably meticulous in craft but prone to tinny highlights and an insipid strain of moralizing.

As for the vaunted “Wanderer above the Sea of Fog,” it is a flat-footed encomium to starry-eyed hubris, an image whose painterly flourishes are as murky as they are nuanced. Still, the finicky strain of portent typifying “The Soul of Nature” shouldn’t scare anyone away from the crystalline moments of grace to which Friedrich was more than capable.