American, Japanese Forces Play Hyped-up ‘Iron Fist’ War Games Against Constant Threat of Communist Chinese Invasion of Taiwan

By DONALD KIRK

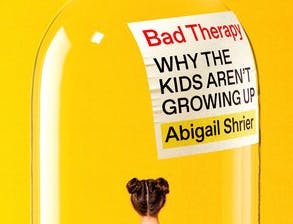

|‘This isn’t a mental health crisis. It’s closer to an emotional hypochondriasis and iatrogenesis crisis,’ Shrier writes.

By DONALD KIRK

|

By LUKE FUNK

|

By BRADLEY CORTRIGHT

|

By JOTAM CONFINO

|

By GEORGE WILLIS

|

By THE NEW YORK SUN

|

By MATTHEW RICE

|

By MATTHEW RICE

|Already have a subscription? Sign in to continue reading

$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

By continuing you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.