‘Agreement’ Shows How Peace Was Made, but Can It Survive Sinn Féin’s Dreams of a United Ireland?

A new play from Belfast brings the Good Friday Agreement to life at a time when the future of Northern Ireland looks increasingly … Irish.

‘Agreement’

Written by Owen McCafferty

Directed by Charlotte Westenra

Irish Arts Center, 726 11th Ave., Manhattan

Through May 12

‘Peace is a very apoplexy, lethargy; mulled, deaf, sleepy, insensible.’

— William Shakespeare, ‘Coriolanus’

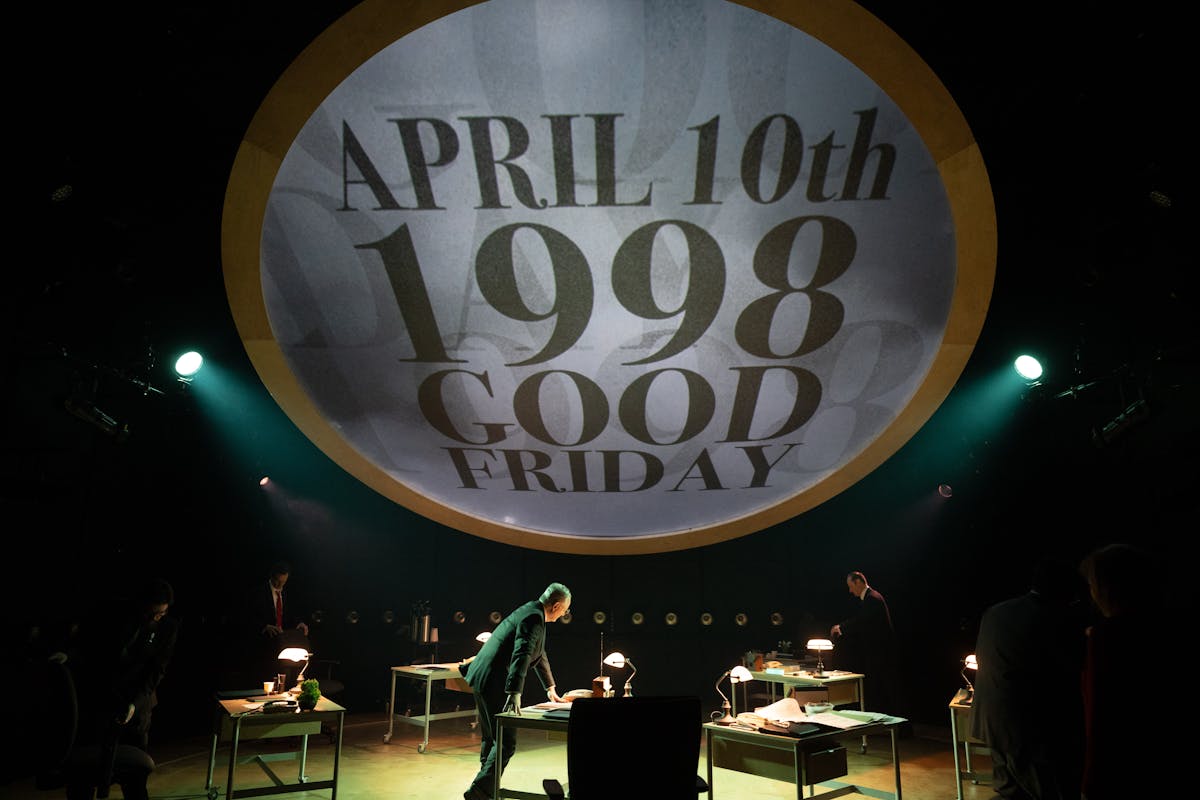

“Agreement,” at the Irish Arts Center, is a propulsive account of the deadline dealmaking that led to the Good Friday agreement among Britain, Ireland, and Northern Ireland. That accord ended decades of violence between the Catholic republicans and Protestant unionists. Like “Hamilton,” the play makes high drama out of papers and proposals. It argues that if the devil is in the details, so are the angels, however begrudging.

The play features seven politicians bunkered down at Belfast in April 1998. Prime Minister Blair (Martin Hutson) is fresh off his landslide. The American envoy, Senator Mitchell (Richard Croxford), brings the magnanimity of a Mainer. The leader of Sinn Féin, Gerry Adams (Chris Corrigan), is a populist with a dry sense of humor. The British secretary of state for Ireland, Mo Mowlam (Andrea Irvine), battles her cancer amidst the bickering.

The Irish Taoiseach, Bertie Ahern (Ronan Leahy), is played with the amiability of a solicitous bartender, though his mother’s death is inconveniently timed. Less familiar to an American audience could be the future first minister of Northern Ireland, the unionist David Trimble (Ruairi Conaghan). Almost more British than the British, Trimble would share the Nobel with the pacifist John Hume (Dan Gordon). There is no peace without their pragmatics.

“Agreement” runs to an hour and 40 minutes with no intermission, and its dialogue is a deluge of disagreement over subjects like “cross-border organizations,” the nature of Northern Irish autonomy, and relations with Westminster. As much discussion obtains of the three negotiating tracks that the characters themselves grow exasperated. Mr. Adams wants his prisoners released. Trimble wants guns decommissioned. You might want a drink.

The play’s power draws not so much from these minutiae — it is no minimization of the violence that wracked the island to feel that the arguments never feel insurmountable — as from the human drama of principle and pragmatism played out across facial expression, posture, and voice. Mr. Adams, who has denied, to skepticism, membership in the Irish Republican Army, has the deadpan manner of a man who is no stranger to armed conflict.

Trimble, the leader of Ulster unionists, must balance his own gravitational pull to London with the offstage presence of the firebrand unionist Ian Paisley, deadset opposed to the very idea of negotiation with the Catholics. Trimble’s taut bearing suggests a roiled interiority. Hume tries to schmooze all sides even as his heart is with those like Messrs. Adams and Ahern, who yearn for the six northern counties to rejoin the Republic of Ireland.

The Arkansan drawl of President Clinton occasionally booms from the rafters, a reminder of the measure of American power at the end of the last millennium. Mr. Blair is played with convincing caricature, a creature of the cameras who lives for the bright lights and pouts when it appears like the grinding negotiations could spoil his vacation in Spain. Everyone in the room wants to get a deal done. The question is: What kind of done deal can they abide?

“Agreement” arrives at a moment when the Good Friday status quo appears to be giving way. For the first time Sinn Féin, the former political arm of the IRA, captured the most seats at Stormont, the devolved parliament. The unionist bloc brought the chamber to a halt by imposing a unilateral boycott. That gave way after extortion from the White House and 10 Downing Street. Astonishingly, the heir to Trimble’s seat, Michelle O’Neal, dreams of a united Ireland.

That aspiration could soon become real. The Irish constitution now “recognises that a united Ireland shall be brought about only by peaceful means with the consent of a majority of the people, democratically expressed, in both jurisdictions in the island.” By law, a referendum must be held if it “appears likely … that a majority of those voting would express a wish that Northern Ireland should cease to be part of the United Kingdom.”

The devotion to the crown held by Trimble and Paisley appears antique. There are now more Catholics than Protestants in Northern Ireland, and Sinn Féin’s leader at Dublin, Mary Lou McDonald, declares that unification is now within “touching distance” and that partition is “now gone: It is now consigned to the pages of the history books.” Or, as the case may be, the stage, where, no doubt, other stories await their change.