Art Historian Pushes Against His Profession’s Tendency Toward Interpretive Overreach

Peter Hecht is an advocate for facts on the ground or, rather, on the canvas. He’s intent on returning the artwork’s agency to the subject under discussion.

Few things make a book reviewer’s eyes glaze over as quickly as the arrival of a compilation of writing about art. Rarefied byways of contemporary culture tend to encourage the intellectual manques within their parameters to indulge in grudgery, theory, and jargon. While every literary genre has its thornier precincts, art history and art criticism are particularly notorious for their hermeticism.

It was with a cautious sense of optimism, then, that I read the preface to “Listening to what you see; Selected contributions on Dutch art,” a new book by a historian and former professor at Utrecht University, Peter Hecht. “I have always tried to write clearly … taking the risk that ‘if I show my cards openly, certain readers will probably think that they cannot be of much interest.'” This quote from Goethe prompts Mr. Hecht to “wish that every academic were made to learn it by heart.”

From Mr. Hecht’s lips to God’s ears, but suspicion is a hard habit to curtail, particularly at a time when postmodern shibboleths and ideological fire-breathing have become the air we breathe. The good professor follows up with a rather unfashionable notion: “Writing about one’s love for art is an obligation not a luxury.” As if he were reading our minds, he lays down the law: “Please do not be cynical about this.”

We’re barely into the first chapter when Mr. Hecht lets us know his thoughts about relativism: “I do not believe that history is so difficult and unknowable that one has to accept all possible and impossible assertions [about art] as being of equal weight and value.” Mr. Hecht is an advocate for facts on the ground or, rather, on the canvas. He’s intent on returning the artwork’s agency to the subject under discussion: “too often … the painter’s poetics seemed to have been all but forgotten.”

“Listening to what you see” is a collection of papers, reviews, and essays that span, roughly speaking, 30 years. As is typical of efforts such as this, Mr. Hecht’s book suffers from a certain repetitiousness, as a number of cherished ideas bob up-and-down through sundry writings. Nor is the book always kind to the layman: Deep dives into iconography may be of serious scholarly import but they’ll likely leave generalists at sea.

The most prominent of Mr. Hecht’s idées fixes is the interpretive overreach of art historians. Although not altogether inclined to dismiss the symbolic underpinnings of Dutch genre painting, he questions whether the images are as rich in signifiers as we have been led to believe. Can’t some artists have been attracted to certain subjects because, you know, they were really good at painting them?

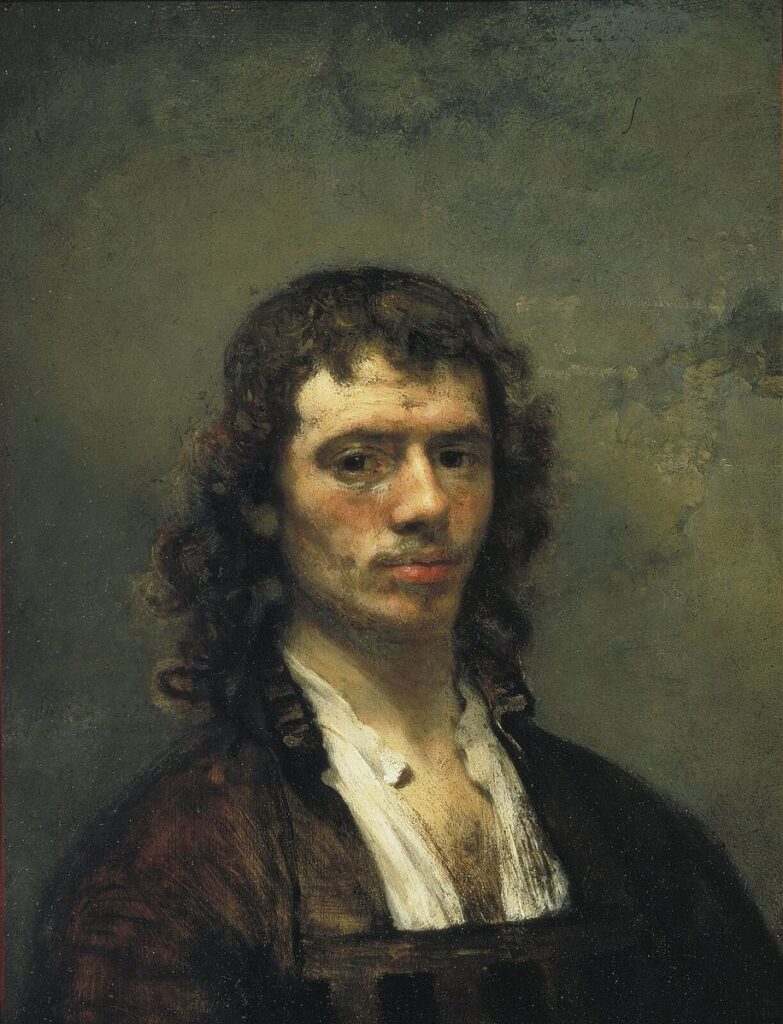

Gerard Dou, a student of Rembrandt and the prototypical fijnschilder, is a constant in Mr. Hecht’s writings and, one suspects, a favorite. Noting that there was “very nearly nothing on God’s earth that Dou’s virtuoso brush could not successfully imitate,” Mr. Hecht posits that perhaps something as straightforward as the delight taken in mimesis accounted for Dou’s considerable success. Who needs moralizing when craft can provide its own rationale?

Dou set out to prove that his chosen metier was superior to sculpture, as Mr. Hecht convincingly argues in a chapter titled “Art beats Nature, and Painting does so best of all.” The author writes about the recurring placement of a relief sculpture, “Putti teasing a goat” (circa 1626-30) by François Duquesnoy, within Dou’s pictures and, in particular, “The violinist” (1653). Roping in Chardin’s “Lady with a bird organ” (1751) to bolster his observations, Mr. Hecht notes that “painting can not only represent all things, but even suggest what music does to nature.”

Elsewhere, Mr. Hecht introduces us to a 17th-century painter and one-trick pony, Godefridus Schalcken; compares Rembrandt and Rubens to the latter’s detriment; and remembers the first time he came across Francisco de Goya’s “Portrait of Don Ramón Satué” (1823). He also dares mention the “Q” word: “The art historian who sidesteps the quality issue is … a rather pitiful specimen.” A gentleman to the end, Mr. Hecht is provocative all the same. “Listening to what you see” is a tonic.