Trump Was Right About Tariffs

By LAWRENCE KUDLOW

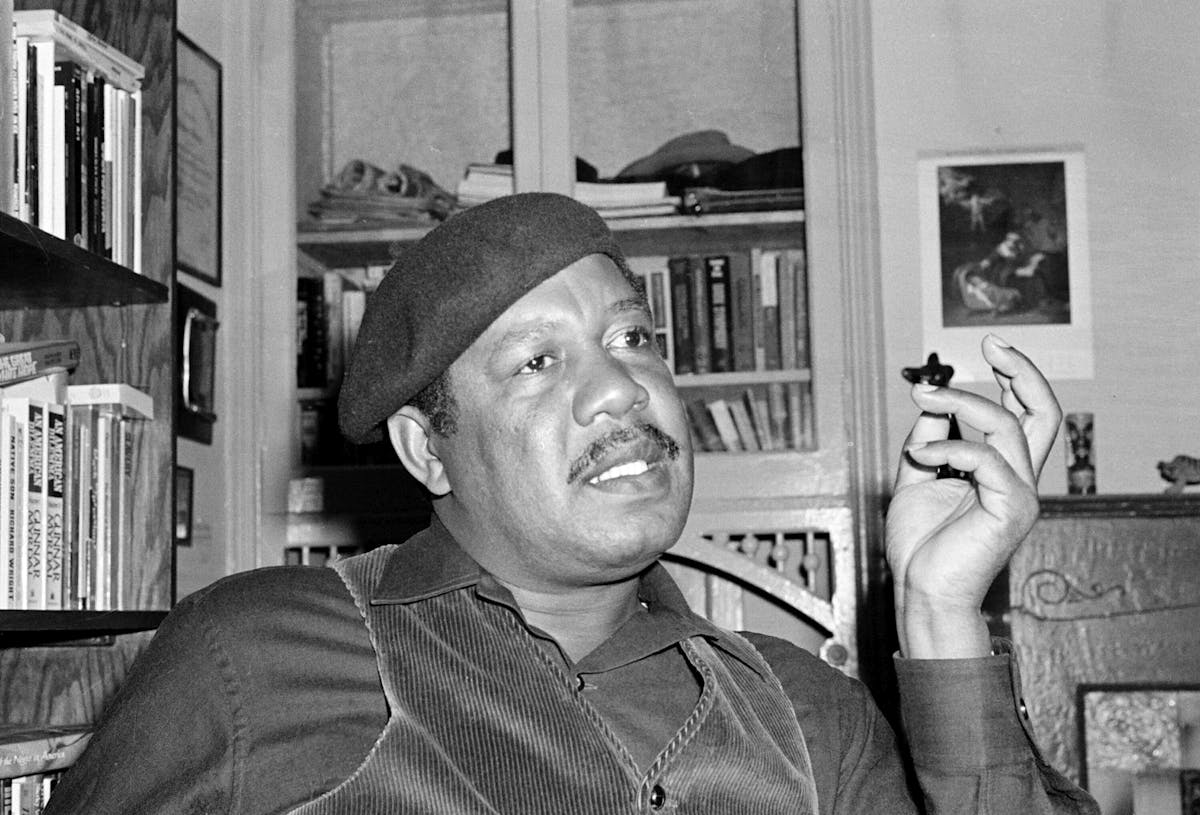

|Ruth Laney’s book is as much about her efforts to preserve what remained of Cherie Quarters as it is a biography of Gaines. It’s a detective story, and she is able to recreate a significant part of a lost world.

Already have a subscription? Sign in to continue reading

By LAWRENCE KUDLOW

|

By HOLLIE McKAY

|

By JOSEPH CURL

|$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

By continuing you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.