The GOP Will Beat History in the Midterms by Sticking to Its America-First Values

By LAWRENCE KUDLOW

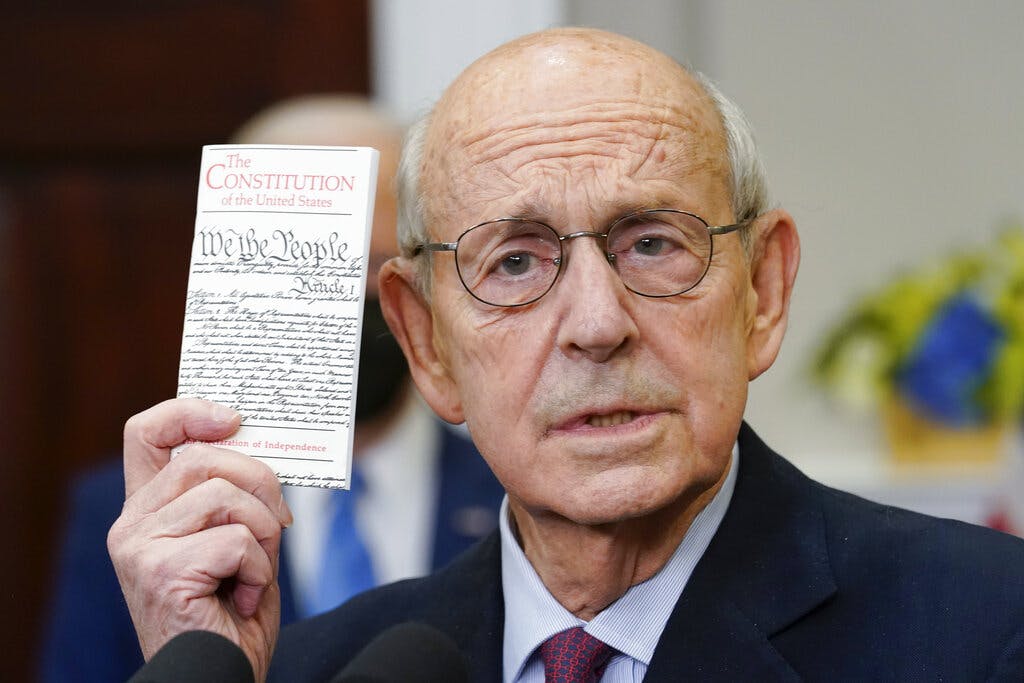

|The one-time justice thinks it would be ‘fine’ to mandate term limits for high court jurists.

Already have a subscription? Sign in to continue reading

By LAWRENCE KUDLOW

|

By MATTHEW RICE

|

$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

By continuing you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.

By LUKE FUNK

|