At Lincoln Center, a Glimpse Inside Jordan Peele’s Head

The program the writer and director has curated, ‘The Lost Rider: A Chronicle of Hollywood Sacrifice,’ is personal indeed: It’s predicated on his most recent picture, ‘Nope.’

What a quirky array of movies the writer and director Jordan Peele has organized for a series that runs January 5-14 at Film at Lincoln Center. There are good pictures in the bunch as well as notable outliers. As someone who earned his showbiz cred as a comedian, Mr. Peele must be relishing the irony in how a toney Upper West Side venue is hosting films whose usual venues are the grindhouse (“Friday the 13th: The Final Chapter”) and the red-state multiplex (“Stand By Me”), as well as VHS oblivion (“Dream a Little Dream”).

Mr. Peele knows that a creative individual is an amalgam, sometimes unwieldy and often contradictory, of any number of influences — good taste be damned. How the artist absorbs, transforms, and makes new these sources is what ultimately determines artistic credibility and, should the resulting work be any good, aesthetic worth. In that regard, the program Mr. Peele has curated, “The Lost Rider: A Chronicle of Hollywood Sacrifice,” is personal indeed: It’s predicated on his most recent picture, “Nope.”

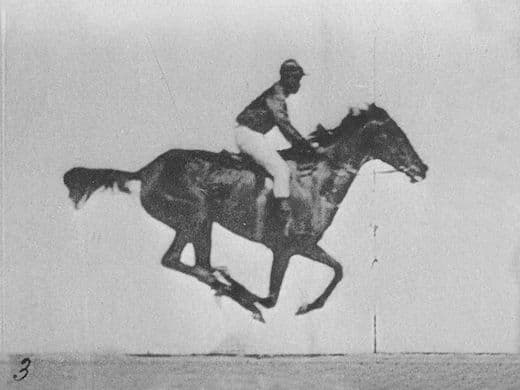

Movie-goers who’ve seen that film will know the significance Eadweard Muybridge’s “Animal Locomotion Plate 626,” a 15-minute film from 1887, has for the director. At Lincoln Center, Mr. Peele is pairing it with the original “King Kong” (1933), the scale of its title character having an affinity with the epic scope of “Nope,” as well as how its alien is predicated on an earth-based animal. Was the character of Ricky “Jupe” Park, the former child actor played by Steven Yeun, connected to Mr. Peele’s apparent fascination with Corey Feldman? Three of the 10 films on view — “Stand By Me,” “Dream a Little Dream,” and “The Birthday” — feature Mr. Feldman.

Admittedly, Mr. Feldman was in his 30s when he starred in the latter, a picture by Spanish director Eugenio Mira that has since gained a cult following. In the press release accompanying “The Lost Rider,” Mr. Peele extols “The Birthday” (2004) as a “cinematic marvel” while the program cites it as “part comedy of manners by way of Jerry Lewis, part phantasmagorical head trip.” Viewers used to milder fare may want to approach this curatorial choice with caution.

No such warning is necessary for “The Wizard of Oz” (1939) — a picture Mr. Peele seems to enjoy as much for the raft of legends surrounding it as for the film itself — or its reimagining as “The Wiz” (1978), starring Diana Ross, Michael Jackson, and, in the title role, Richard Pryor. “Buck and the Preacher” (1972), a revisionist Western that features Harry Belafonte and Sidney Poitier, who also directed, should find an enthusiastic audience, particularly given the chemistry between its two leads.

“Come and See” (1985), in stark contrast, is not an easy film by any stretch of the imagination. Directed by Elem Klimov, it is a near-hallucinatory recounting of the German occupation of Belarus during World War II. As seen through the eyes of 14-year old Flyora (an unforgettable Aleksei Kravchenko), “Come and See” is as uncompromising a war film as one could imagine or want, an achievement of almost untenable proportions. Mr. Klimov never made another film: “Everything that was possible I felt I had already done.” It’s not hard to fathom how “Come and See” could take that much out of a man.

“Nope” both opens and closes the program. Mr. Peele, along with some of the film’s crew, will participate in a Q&A on the evening of January 5. Whether he will bypass the academic cant for which he betrays a weakness remains to be seen. “King Kong,” for instance, concerns itself with “exotic masculine spectacle.” Whatever you say, Professor Peele.

In the meantime, “The Lost Rider” offers a glimpse into the head of a man who has, over the span of a mere three movies, proved to be a born filmmaker.