At MoMA, Problems of Race as Film Moves Beyond Black and White

Good luck trying to avoid tussling with the controversies surrounding America’s racial history upon watching the most noteworthy film of the series, ‘King of Jazz’ (1930).

‘Eye Candy: The Coming of Color’

August 23-September 6

‘Before Technicolor: Early Color on Film’

Through Spring

Museum of Modern Art

Fame is ephemeral and retrospect often unforgiving: This fairly obvious truism applies to, among myriad others, Paul Whiteman (1890-1967), an inescapable figure in American popular music for whom time and taste have not been kind.

Whiteman, nicknamed “The King of Jazz,” helmed one of the most popular big bands during the 1920s and ’30s, and did much to popularize the artform. He cut a striking figure — Whiteman comes on like a nattier Oliver Hardy — and hired some of the best musicians in the business, including legendary figures like Bix Biederbecke and Jack Teagarden. Among his achievements was asking George Gershwin for something that later became known as “Rhapsody in Blue.”

Whiteman was also that most loathsome of creatures: a cultural appropriator. Although he was supportive of African-American musicians — he commissioned pieces from Duke Ellington; worked with arrangers like William Grant Still and Don Redman; and provided backing for Paul Robeson’s signature version of “Ol’ Man River” — his music has been deemed over-orchestrated, tasteful to a fault, and exclusionary. Sweeping Whiteman under the rug is, by jazz cognoscenti, the preferred manner by which to acknowledge him.

That being said, good luck trying to avoid tussling with the controversies surrounding Whiteman or America’s racial history upon watching “King of Jazz” (1930), a film included in “Eye Candy: The Coming of Color,” a series of pictures presented by the Museum of Modern Art in conjunction with the exhibition “Before Technicolor: Early Color on Film.”

As curators James Layton and David Kehr remind us, color movies have been with us, in one form or another, since 1895. That color was once considered “a white elephant to the cinematic medium” will likely come as a surprise to audiences today.

“Eye Candy” was organized by a curator in the Department of Film, Ron Magliozzi, and includes a number of noteworthy pictures, such as the original (and best) “Phantom of the Opera” (1925), with Lon Chaney in the title role; Cecil B. Demille’s first go-round with “The Ten Commandments” (1923); and the seminal science fiction movie “A Trip to the Moon” (1902), by Georges Méliès. Also included are experimental films by Len Lye and Oskar Fischinger, bopping arrays of shape, geometry, and text that would later be lampooned by Mel Brooks in his Academy Award-winning short “The Critic” (1963).

Still, “King of Jazz” is the most noteworthy of the bunch and not just because it will rankle contemporary sensibilities. You don’t have to be the wokest bloke on the block to rue an era in which African Americans were explicitly denied their role in shaping American pop culture, as is the case here with “Melting Pot of Music,” the grand finale of “King of Jazz.” As for that appellation, Whiteman neither generated nor declined it. As a man who stated that “jazz came to America three hundred years ago in chains,” he was wise to the irony implicit in his royal status.

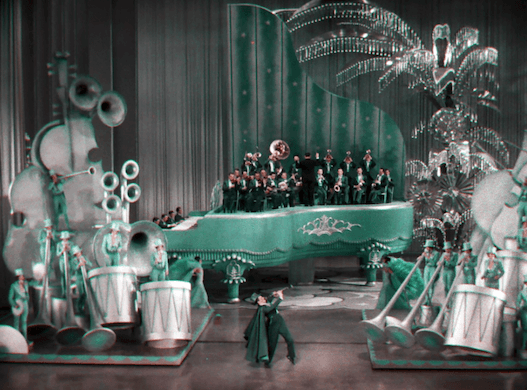

Having said all that, “King of Jazz” is wild and weird, an old-fashioned entertainment that has accrued an almost hallucinogenic patina. It’s a variety show, basically: a trundling out of musical numbers, dance routines, novelty acts, comedic aperçus, and even a cartoon. Built around the conceit of “Paul Whiteman’s Scrapbook,” the movie turns its pages through some glitzy nightclub settings that have a lot of moving parts and are often gargantuan in scale. Universal Pictures sunk a pretty penny into this venture.

The studio didn’t recoup its costs — “King of Jazz” was later dubbed “Universal’s Rhapsody in Red” — and the critical consensus was, you know, meh. Perhaps audiences had to reconnoiter after the initial all-talking, all-singing novelty of sound had begun to wear thin. That didn’t prevent one young man from achieving greater things. Yes, that’s a cherry-pink Bing Crosby making his feature movie debut as one of The Rhythm Boys, the vocal component of Whiteman’s orchestra.

“King of Jazz” was filmed in a process keyed to green and red, and the resulting film has a softly saturated, almost spongy tactility. The narrow range of chroma — at moments sickly sweet, at other times acidic — gives the picture an otherworldly tenor. The 10-minute segment dedicated to “Rhapsody in Blue” tends toward a velvety aquamarine and is kaleidoscopic in its “Alice in Wonderland” shifts in scale. How this film didn’t become a staple back in the heyday of Haight-Ashbury, I don’t know.

Director John Murray Anderson seems to have been channeling the Russian Constructivists in his employment of skewed camera angles, abrupt close-ups, and crisply defined choreography. Herman Rosse, a veteran of Broadway stagecraft, won an Oscar for Best Art Direction and then, in a filip that isn’t as counterintuitive as it might seem, went on to design the sets for James Whale’s “Frankenstein” (1931).

As for the toy-like line-up of chorines known as the Russell Markert Dancers: they eventually morphed, fancy that, into the Rockettes. Their renown remains undiminished here in 2023 — unlike that of Whiteman, who is the affable locus of a perpetually stupefying film. “King of Jazz” is a trip. Kudos to MoMA for making it available on the big screen.