At the Met, Baseball Cards Hang Next To the Other Old Masters

These mini-masterpieces give face and form to those who played with force and grace and are now dust and statistics.

Like shuffling through a pack of baseball cards to find the special insert, finding the ballplayers amid the portraits and triptychs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art takes a little bit of work, or at least a scenic tour through the Medieval and Byzantine wings of the Fifth Avenue sanctum. You’re looking for the pitchers, not the pharaohs.

You’ll find the boys of summer nestled in the mezzanine section of the American Wing. The “Baseball Cards from the Collection of Jefferson R. Burdick,” open through October 25, features more than 100 cards from between the late 19th century and the middle of the last one. Fragments of popular culture that retain their charm, the cards give face and flesh to those who played with force and grace and are now dust and statistics.

Burdick, who was an electrician at Syracuse, amassed a gargantuan collection that encompasses 30,000 baseball cards along with what the Met describes as “another 303,000 trade cards, postcards, and posters.” He gave all of it to the museum, which describes the cards as illustrating “the history of baseball from the dead-ball era, at the turn of the nineteenth century, through the golden age and modern era of the sport.”

Baseball cards, the Met informs, “were issued by tobacco companies in the wake of the Civil War to market cigarettes and loose tobacco.” Tobacco yielded to chewing gum in the 1930s, so that children unwrapping the sticky stuff could find their heroes in miniature.

The oldest cards in the exhibit, which date from 1888 and were manufactured by Allen & Ginter, are done in lovely pastels, executed with a kind of watercolor technique. Profiles of the players are set against renderings of scenes from the game’s infancy: The players wear no gloves because they had not yet become de rigueur.

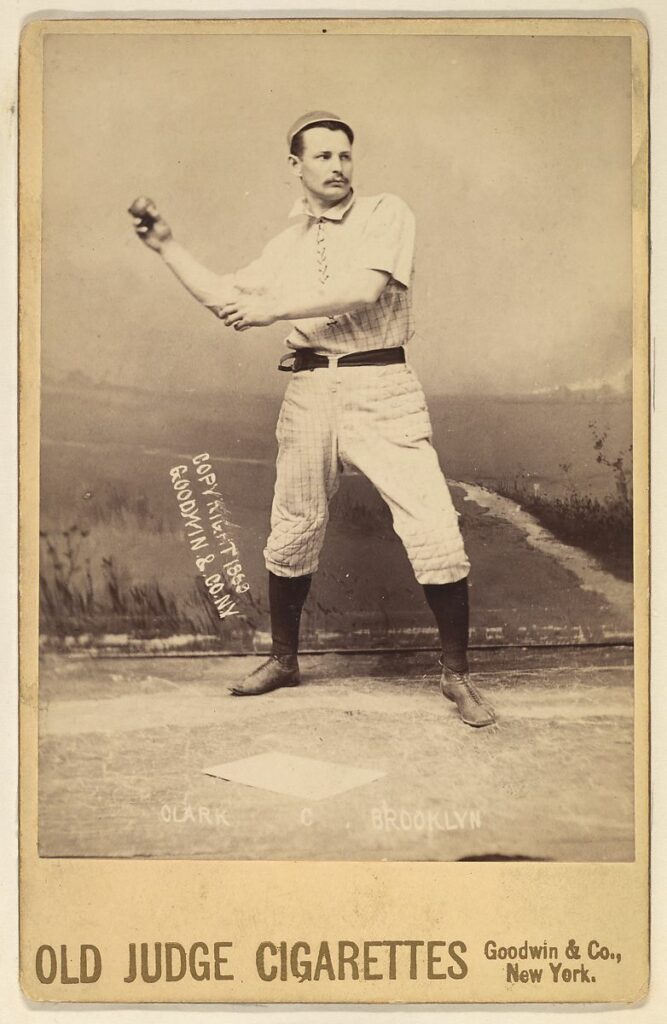

The dedicated fan will thrill to the sight of William “Buck” Ewing, who starred for the New York Gothams, ancestor to the Giants. Ewing became, in 1939, the first catcher elected to the Hall of Fame. Another set, “Old Judge Cigarettes Cabinet Cards,” features photographs that capture players in action poses. Catch Bob Caruthers, who pitched for the Brooklyn Bridegrooms and likely deserves a spot in the Hall of Fame.

A series from 1914 and 1915, “Ball Players for Cracker Jack,” features immortals of the game against a red background, bringing to mind an Andy Warhol silkscreen. On display is Ty Cobb, with his choked up bat and high collar; Honus Wagner,“The Flying Dutchman,” the greatest shortstop who ever lived; Charles Albert “Chief” Bender, who was said have invented the slider; and Johnny Evers, the second baseman known as the “Human Crab.”

The scowling Charles Comiskey, who owned the Chicago White Sox and was so miserly his players threw the 1919 World Series for petty cash from Arnold Rothstein’s outfit, hangs next to creased cards of a young George Herman “Babe” Ruth, manufactured by the American Caramel Company. The Babe is shown pitching, a reminder that he was an ace on the mound before he was a slugger at the plate.

Cards from 1939 feature a steely gaze from Charlie Gehringer, known as “The Mechanical Man” for his unerring reliability, and a warmer one from his teammate “Hammerin’” Hank Greenberg, a slugger who was robbed of four prime years on the diamond on account of his military service in World War II. No player served for longer than Greenberg, who spent Yom Kippur in 1934 in synagogue in the midst of a closely fought pennant race.

The Goudey Gum Company plastered the great Mel Ott — he of the high leg kick and soaring home runs — against bright blues, yellows, reds, and greens. “Joltin’” Joe DiMaggio — of whom Secretary Kissinger once said, “If you told me in 1938 that I would be Secretary of State, and I would be friends with DiMaggio, I would have thought the second was less likely than the first” — is captured in both a photograph and a cartoon.

The show concludes with cards that feature signed drawings of Willie Mays, Monte Irvin, and Don Newcombe, all of whom played in the Negro Leagues and then would go on to star in the majors. The cards are a reminder that for more than a century some of the sport’s best players were barred from the field, and baseball cards, on account of their race.

Fortunately, their rise to glory is reflected in this wonderful exhibit. Their cards, of course, have become big business: A 1952 Mickey Mantle number is expected to go for $10 million at an online auction that closes on August 27, and last year a 1909 Honus Wagner card was sold for nearly $7 million. There are Rembrandts that could be had for less.