At the Met, ‘The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism’ Proves a Worthy, If Somewhat Uneven, Draw

Historical context and artistic comparisons are important, but they’re applied only selectively throughout the installation and, in the end, serve basically as a half-hearted, oh-by-the-way inclusion.

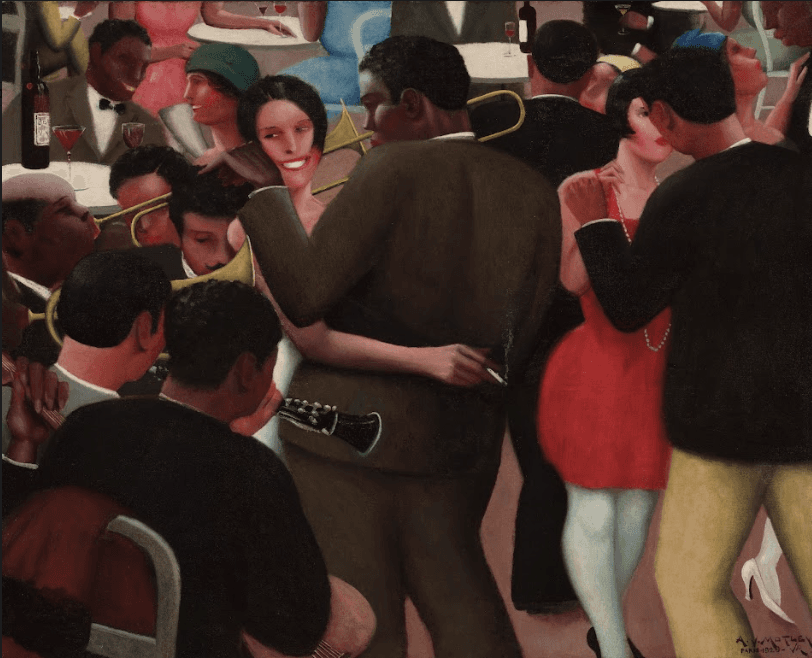

The American painter Archibald J. Motley Jr. (1891-1981) is likely best known for his multi-figure compositions depicting the variousness of Black life in America — of backroom card games, elegant formal dinners, “holy rollers” in church, bustling commercial thoroughfares, and rambunctious jazz clubs.

The paintings are luminous and funny, bumptious in their forms, often lurid in ambiance and velvety in tactility. Canvases like “Blues” (1929), “Black Belt” (1934), and “Nightlife” (1943) underscore the urbanity that is at the heart of an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, “The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism.”

Whether these are the finest examples of Motley’s oeuvre is a question worth asking. Notwithstanding their considerable appeal, the pictures have always seemed stilted, like inventories of stuff crammed together rather than organic wholes given life. Motley’s cultural investment in the pictures is clear, but was his temperament?

Take into account the somewhat persnickety personage we see in “Self-Portrait” (circa 1920) or, even better, “The Octoroon Girl” (1925) and the radiant “Brown Girl After the Bath” (1931). The latter two are supernal paintings, each possessed of an equanimity whose quietude did not exclude a frank embrace of sensuality. Notwithstanding the generic titles of each canvas, these are portraits of individuals, hard-won and shaped with exquisite command.

Motley isn’t the only artist who is seen in abundance during the run of the Met exhibition. James Van Der Zee’s photographs, whether they be of tea time at the beauty parlor or a shoeless street preacher, are, as documents of an era, silky and stern. William Henry Johnson’s chock-a-block portraits, owing as much to vernacular art as to Van Gogh and Soutine, are invariably bracing, and the portraiture of Laura Wheeler Waring, whether it be of an unnamed young woman or Marian Anderson, is of a high order.

You know what’s on view of a lesser or, rather, unnecessary order in “The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism”? Pictures by Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Kees van Dongen, Chaim Soutine, and Edvard Munch.

Granted, the exhibition’s intent is to “situate Black artists … as central to our understanding of international modern art and modern life.” Denise Murrell, the museum’s Merryl H. and James S. Tisch curator at large and organizer of the show, speaks of how “many New Negro artists spent extended periods abroad and joined the multiethnic artistic circles in Paris, London, and Northern Europe.”

Historical context and artistic comparisons are important, but they’re applied only selectively throughout the installation and, in the end, serve less as a grounding for the Met’s ambitions than a half-hearted, oh-by-the-way inclusion.

Is it interesting to learn that Matisse visited jazz clubs on his visits to Manhattan and, from some accounts, hobnobbed with Billie Holiday and Louis Armstrong? Absolument, but the corresponding pictures are marooned in this particular outing. Would that Ms. Murrell had placed van Dongen’s “Plumes Blanches” (1910-1912) next to Beauford Delaney’s “Dark Rapture (James Baldwin)” (1941). I mean, talk about “cross cultural affinity.” Such pairings are few and far between.

Be that as it may, “The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism” is a rare creature, an unapologetic crowd pleaser of genuine scholarly merit. Whatever complaints that can be accrued by rote nods to ideological fashion are subsumed by the quality and range of the work itself. Accompanying the paintings, drawings, sculptures, and prints are a host of documentary items, including copies of The Crisis, a magazine founded by W.E.B. Dubois, and a loop of film featuring Josephine Baker and sundry other nightclub talents.

Let’s hope the success of this venture results in deeper elaborations of individual oeuvres — say, the metaphorical totems of Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller or the prismatic symbolism of Aaron Douglas. In the meantime, here is an exhibition of considerable merit, gravity, and joy.