Can Trump ‘Nationalize’ Elections?

By THE NEW YORK SUN

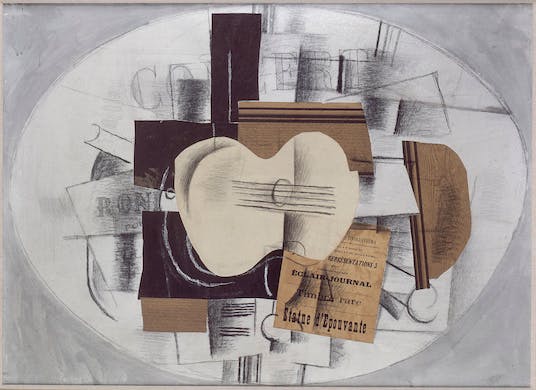

|‘Cubism and the Trompe l’Oeil Tradition’ achieves what one hopes of any exhibition; it prompts us to reconsider what we thought we knew.

By THE NEW YORK SUN

|

By JOSEPH CURL

|

By LAWRENCE KUDLOW

|

By BRADLEY CORTRIGHT

|

By MATTHEW RICE

|

By LUKE FUNK

|

By BENNY AVNI

|

By JOSEPH CURL

|Already have a subscription? Sign in to continue reading

$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

By continuing you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.