Barkley Hendricks’ ‘Astonishing’ Portraits Bring a Frisson of Magic to the Frick Madison

A missed opportunity, curatorially speaking, but it’s worth visiting for the opportunity to view Hendricks’s pictures on a piecemeal basis.

‘Barkley L. Hendricks: Portraits at the Frick’

The Frick Madison, 945 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10021

Through January 7, 2024

“You see a lot of people paint jeans. But no one paints jeans like me.” Or so the American artist Barkley L. Hendricks (1945-2017) told Laila Pedro in a 2016 interview for the Brooklyn Rail. Get up close to “APB’s (Afro-Parisian Brothers)” (1978), a canvas currently on display at the Frick Madison, and you’ll realize that Hendrick’s braggadocio was well-earned.

Navigating the illusory capabilities of oil paint with the material implacability of the canvas weave, Hendricks applied slurs of blue against a ground of related color to create a frisson of magic that is an inherent to the painter’s craft.

Then take the stairwell downstairs and reacquaint yourself with “The Hon. Frances Duncombe” (ca. 1777) by Thomas Gainsborough. At the risk of incurring the wrath of the security guards, inch up to its surface and take note of how Gainsborough brought her raiment into fruition by allowing his brush to glance upon an underlying layer of blue.

Here is where the erstwhile British portraitist and Hendricks, a native Philadelphian, commune with each other over the distance of centuries, geographies and cultures: in the suppleness of paint-handling and acuity of color. Would that “APB’s (Afro-Parisian Brothers)” and “The Hon. Frances Duncombe” were hung side-by-side.

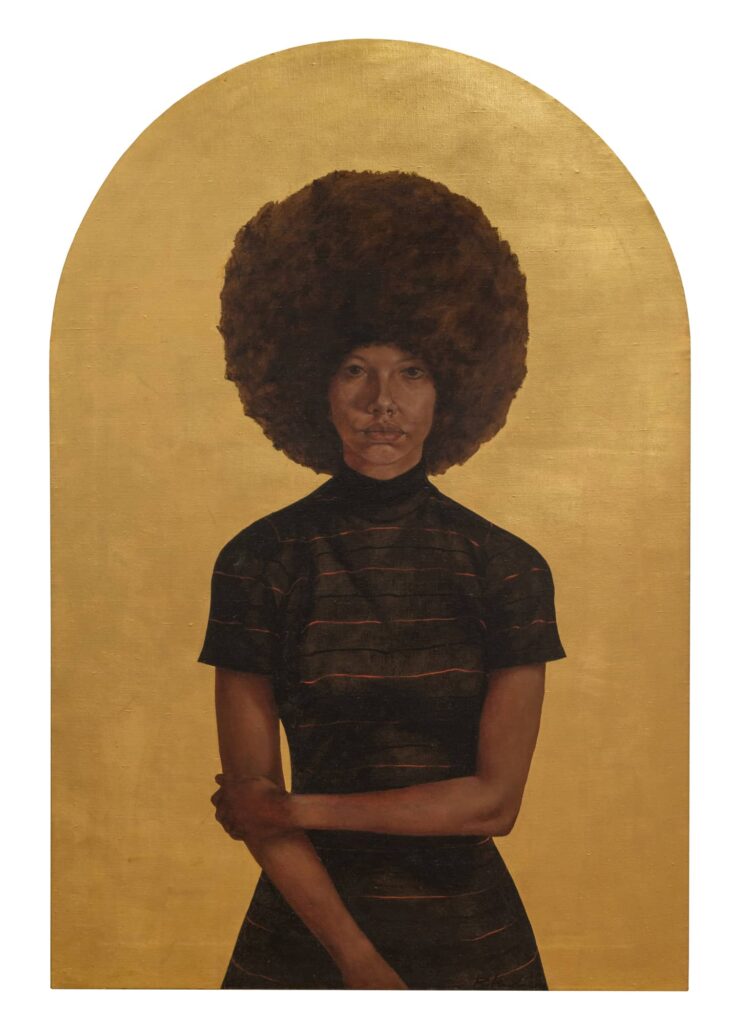

Which begs the question: why weren’t they? Upon exiting the elevator to view “Barkley L. Hendricks: Portraits at the Frick,” New Yorkers will encounter “Lawdy Mama” (1969), a realistic rendering of a young African-American woman set against a field of gold leaf.

The allusion to Byzantine painting is obvious, as is the irony of Hendricks’s nestling a contemporary secular figure within a format redolent of religious iconography. The title, excerpted from a song by Nina Simone, both undergirds and confirms the picture’s devotional basis. Hendricks liked his jokes sardonic.

“Lawdy Mama” has been placed, to curious effect, between two 18th-century busts by the French neoclassical sculptor Jean Antoine-Houdon. Each of them is a portrait, I guess, and if we’re going to talk interior decoration, the earthy tones and metallic glint of Hendricks’ painting generate an effective contrast to Houdon’s absorbent surfaces.

Even allowing that charitable interpretation, the placement is kind of pointless. Situating Hendricks’s canvas — a portrait of a distant cousin and not, as it is sometimes assumed, Angela Davis — near the Frick’s “The Coronation of the Virgin” (1358) by Paolo and Giovanni Veneziano would have been more fitting and, I think, more provocative.

As it is, an exhibition that seeks to underscore how Hendricks’s “astonishing portraits of predominantly Black figures . . . appear right at home among [the Old Masters]” succeeds more by institutional context than by establishing a true conversation between painters.

“Portraits at the Frick” does attempt to do right by Hendricks by installing a group of monochromatic canvases by James Abbott McNeill Whistler a stone’s throw from Hendricks’s signature “white-on-white” pictures, a body of work created largely during the 1970s. Yet a stone’s throw isn’t a tête-à-tête.

Elsewhere at the Frick, you’ll find the unfortunate paintings of contemporary artist Nicolas Party hung in direct relation with their inspiration, Rosalba Carriera’s “Portrait of a Man in Pilgrim’s Costume” (ca. 1730). Why Hendricks, an infinitely more capable artist, wasn’t allowed the same courtesy, I don’t know.

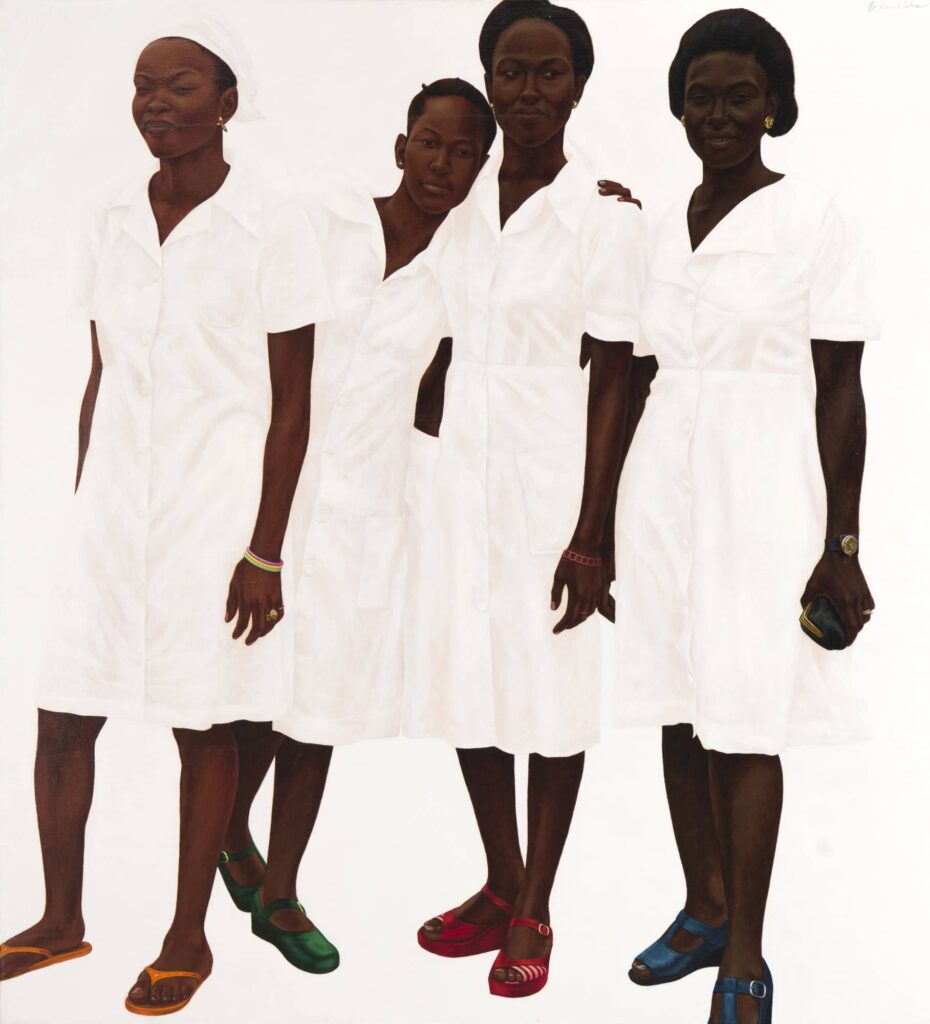

The best part of “Portraits at the Frick” is the gallery set aside for the aforementioned “white-on-white” works: they are among the most audacious paintings of the latter half of the 20th-century.

Placing dark-skinned individuals within apparel and spaces that couldn’t be more stark in contrast is a pointed tack, sure, but consider the work’s formal daring, as the interstices between figure and ground are tested, rendered ambiguous and, in the end, made to crackle with pictorial tension.

The painterly authority embedded within something like “Lagos Ladies (Gbemi, Bisi, Niki, Christy)” (1978) is inescapable and, in the end, thrilling.

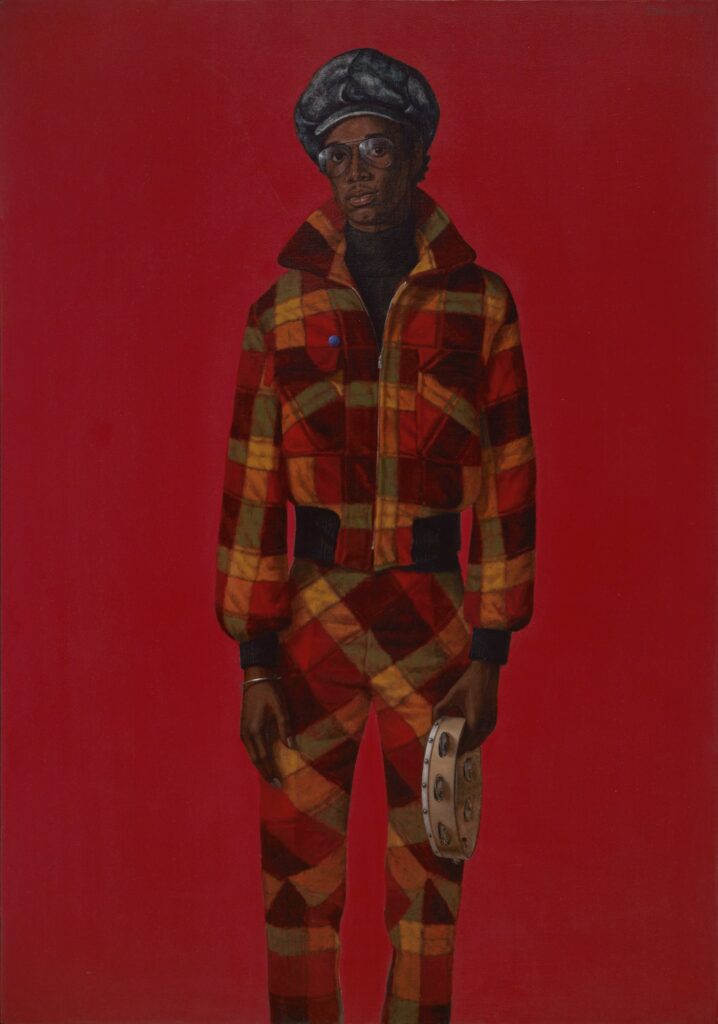

“Portraits at the Frick” remains, on the whole, a missed opportunity, but it’s worth visiting for the opportunity to view Hendricks’s pictures on a piecemeal basis, as well as to wonder what “Blood (Donald Formey)” (1975), with its smoldering light-filled patterning, might have to say to the luminously bedecked “Sir Thomas More” (1527) by Hans Holbein the Younger. Oh, well — next time.