Biographies: The Ahab of American History

A magnificent new biography of the still relevant advocate of secession.

‘Calhoun: American Heretic’

By Robert Elder

Basic Books, 640 pages, $35

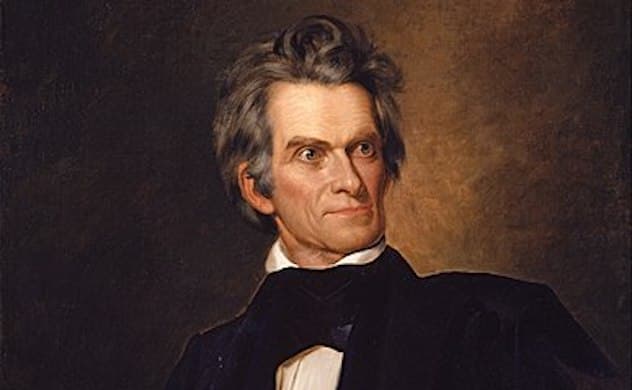

John C. Calhoun (1782-1850) is the Ahab of American history. That is why Robert Elder’s epigraph to his magnificent biography is from “Moby-Dick”: “There was an infinity of firmest attitude, a determinate, unsurrenderable wilfulness, in the fixed and fearless, forward dedication of that glance.”

Certain portraits of the seventh U.S. vice president make him look like Satan incarnate.

Calhoun is best known as the relentless advocate of nullification, the notion that a state could invalidate a federal law. He argued that the Union was a compact of states that had never relinquished their sovereignty — that, indeed, the very conception of sovereignty meant a state could not abnegate its independence.

For many historians Calhoun’s doctrine is irrevocably connected to his defense of slavery and thus, as Richard Hofstader contended, the South Carolina politician’s ideas have “little more than antiquarian interest.”

Not so, Mr. Elder’s biography shows. In fact, Calhoun’s articulate defense of minority power, albeit held in the hands of slaveholders, has resonated with legal thinkers such as Lani Guinier, a woman of color.

Guinier’s book “Tyranny of the Majority” recognizes that sometimes “even when rules are perfectly fair in form they serve in practice to exclude particular groups from meaningful participation.” There has to be a mechanism, she believes — as did Calhoun — perhaps a supermajority that would in effect be a minority veto of issues critical to the minority.

In 1798, Jefferson used the word nullification to declare that a state can deem an unconstitutional federal law “void & of no force.” The New England states as early as 1803 considered secession and did so again during the War of 1812. Calhoun did not broach the idea of nullification until 1841, and in his view the word did not signify disunion.

Calhoun served in the federal government on good terms with New Englanders like John Quincy Adams, agreed with Federalists about the need for a strong national standing army, and for many years seemed a likely presidential candidate. Mr. Elder presents a strong case for Calhoun’s desire to preserve the union.

Calhoun proposed a cumbersome convention to settle the challenges of nullifiers who could be overruled only by three-quarters of the states. He believed in a dynamic Constitution that had to adapt to changing times and shifting power relationships. Yet he never proposed a practical mechanism for adjudicating disputes about federal law, apparently regarding the Supreme Court as an insufficient authority.

Calhoun might well have become president with significant support in the North if he had not overturned generations of thought about the nature of slavery. Rather than calling it a necessary evil, as Jefferson, Madison, and other illustrious Southern predecessors did, he declared the “peculiar institution” a positive good.

If Calhoun had not promoted a fiction that slaveholding acted to civilize primitive Africans, he might have made common cause with legislators outside the South, since racism was rampant in all regions and abolitionists were unpopular.

Instead, his arguments strengthened the resolve of slaveholders to spread slavery into the territories and alienated politicians in the North and West who regarded Calhoun’s pro-slavery position as perverse and secessionist.