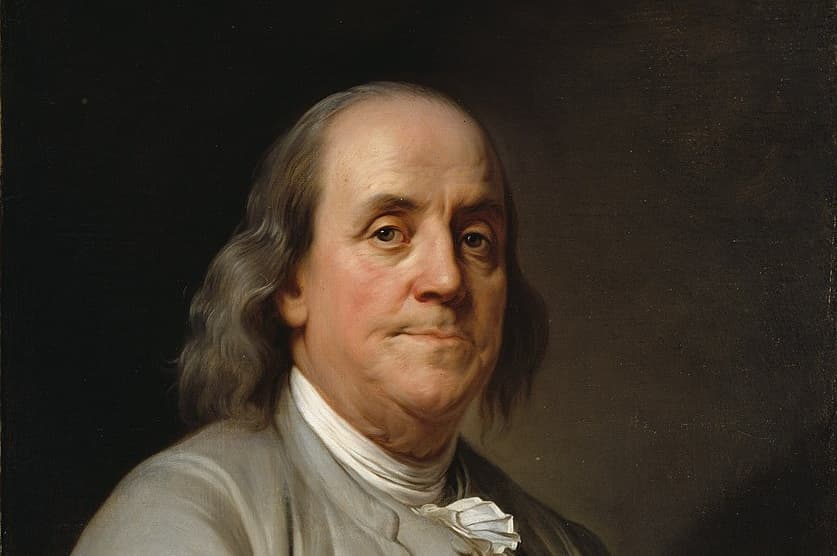

Can Donald Trump Escape Jack Smith and Find Redemption Thanks to Ben Franklin and a Beheaded King Charles I?

A remark from the author of ‘Poor Richard’s Almanack’ could well sway the Supreme Court on the crucial issue of immunity.

Would Benjamin Franklin, newly portrayed in an Apple TV + series, support President Trump’s claim of absolute immunity as constitutionally sound or denounce it as a recipe for tyranny? Could the fate of a beheaded king foreshadow the decapitation of Mr. Trump’s political career — and cost him his liberty?

Those questions are no joke. They are raised by the citation of the Founding Father by one of Mr. Trump’s attorneys, John Sauer. It came before no less an audience than the Supreme Court during oral arguments over whether the 45th president is entitled to immunity for his actions in attempting to overturn the 2020 election.

Mr. Sauer told Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson that Franklin declared, “History provides one example only of a chief magistrate who is subject to public justice, criminal prosecution. Everybody, he reminded her, cried out against that as a violation.*” The lawyer insists that this statement “reflects best the Founders’ original understanding and intent.”

The Supreme Court advocate marshaled the quotation to rebut Justice Jackson’s presumption that “every president from the beginning of time essentially has understood that there was a threat of prosecution.” Justice Jackson conceded the point, allowing, “No, I understand, but, since Benjamin Franklin, everybody has thought, including the presidents who have held this office, that they were taking this office subject to potential criminal prosecution, no?”

Oral arguments were not the first time Mr. Trump turned to this quotation from Franklin to bolster his case. The Philadelphian appears in the former president’s last brief docketed at the high court, filed on April 15. Franklin is the first authority cited in a section labeled “Historical Sources Support Immunity,” where he is summoned to refute Special Counsel Jack Smith’s assertion that criminal immunity “would have been anathema to the Founders.”

Mr. Trump’s attorneys, though, quote only the first part of Franklin’s reflection, which is preserved in James Madison’s notes and attributed to “Docr. Franklin” in recognition of an honorary degree received in 1759 for his experiments with electricity. The comment was originally uttered at the Constitutional Convention, on a Friday — July 20, 1787. Franklin, at 81 years of age, was the oldest delegate and had to be carted in on a sedan.

Madison records Franklin observing, “History furnishes one example only of a first Magistrate being formally brought to public Justice. Everybody cried out against this as unconstitutional. What was the practice before this in cases where the chief Magistrate rendered himself obnoxious? Why recourse was had to assassination in which he was not only deprived of his life but of the opportunity of vindicating his character.”

Franklin went on to reckon that it “would … be the best way therefore to provide in the Constitution for the regular punishment of the Executive where his misconduct should deserve it, and for his honorable acquittal when he should be unjustly accused.” The reference is to impeachment, at which Mr. Trump was twice secured of what Franklin called “an honorable acquittal.”

The “first magistrate” Franklin refers to is Charles I. He reigned as king of England, Scotland, and Ireland from 1625 until he was executed in 1649 for high treason, after the Parliamentarians defeated the Royalists, for a time, in the English Civil War. The king protested that “no earthly power can justly call me (who am your King) in question as a delinquent … this day’s proceeding cannot be warranted by God’s laws; for, on the contrary, the authority of obedience unto Kings is clearly warranted, and strictly commanded.”

The verdict, though, was soon read out: “For all which treasons and crimes this court doth adjudge that he, the said Charles Stuart, as a tyrant, traitor, murderer, and public enemy to the good people of this nation, shall be put to death by the severing of his head from his body.” The monarchy was abolished and England declared a republic under a Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell.

By 1660, though, Charles’s son, Charles II, was back on the throne, and the political winds had shifted. Charles I was canonized as a saint by the Church of England. Parliament’s website explains that after the Restoration, Charles’s death warrant “was used to identify the commissioners who had signed it (the ‘regicides’) and prosecute those who could be captured for treason. Even the signatories, who had died, including Cromwell, were dug up and their bodies hanged.”

The question of how to punish “first magistrates” — presidents and kings — was not entirely a theoretical one for Franklin or the other delegates, who had just recently affected a divorce from King George III. It was Judge Tanya Chutkan, of the trial court, who in denying immunity warned Mr. Trump that he did not possess the “divine right” once claimed by Charles I. Now, though, it could be Franklin, meditating on a dead king, who throws him a lifeline.

______________________

* Franklin said that “everybody cries out against this as unconstitutional.” Mr. Sauer, in oral argument, interpolated “a violation.”