Iran Adds 7 Years to Prison Sentence for Nobel Laureate Narges Mohammadi

By SUN STAFF and ASSOCIATED PRESS

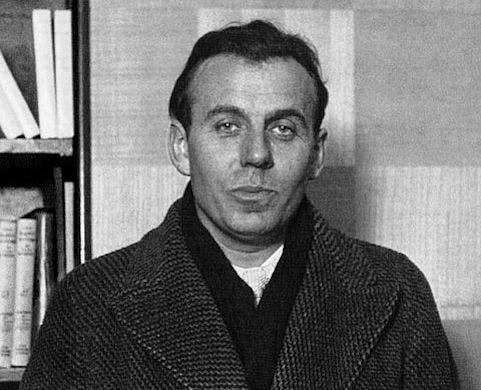

|Céline had good reason to see the Reich as a safe haven. He wrote a range of antisemitic tracts and advocated collaboration with the Nazis.

Already have a subscription? Sign in to continue reading

By SUN STAFF and ASSOCIATED PRESS

|

By MATTHEW RICE

|

$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

By continuing you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.

By DAVID JONES