Consisting of Impressionistic Vignettes of Black Life Circa 1972, Charles Burnett’s ‘Killer of Sheep’ Earns a Revival

Burnett’s picture doesn’t concern itself with anything so concrete as a plot. We get to know the denizens of the protagonist’s neighborhood through an accumulation of moments. Evocation rather than explication is the rule.

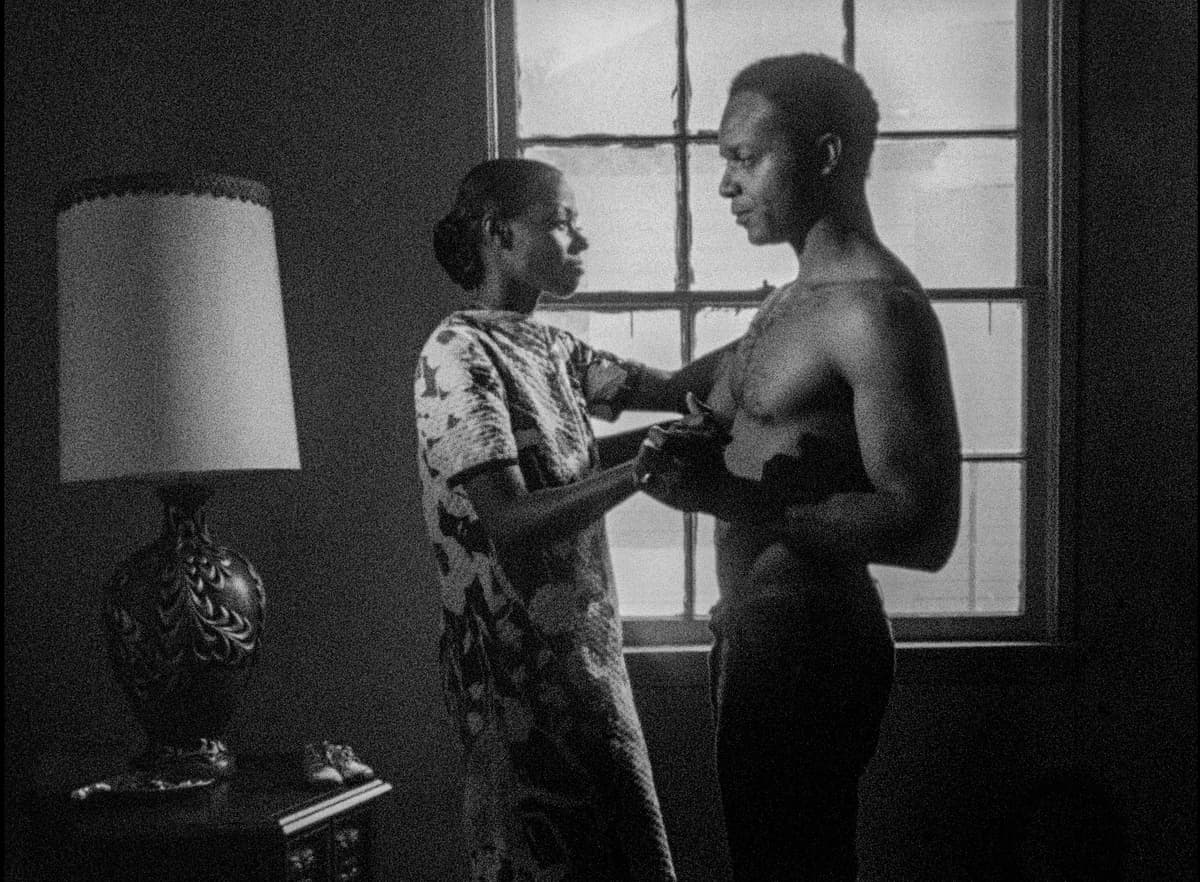

The tender comforts and unspoken disappointments of marriage are captured on screen with remarkable understatement in Charles Burnett’s “Killer of Sheep” (1977), a film soon to be undergoing a revival at Film Forum. A little more than halfway through Mr. Burnett’s wandering meditation on the workaday travails of life, our protagonist, Stan (Henry G. Anders), dances with his wife (a brooding and lovely Kaycee Moore) to “This Bitter Earth,” a song by Dinah Washington.

The scene can’t last more than a minute. The couple is in a darkened room, silhouettes swaying in front of a window lit from outside, by a street lamp perhaps. Stan is shirtless; his wife — she’s not identified by name — wears an evening gown with a strong floral print. Has a night on the town been planned?

They move slowly. Stan’s wife relishes the physical contact just as plainly as her husband is torn between duty and distraction. The song ends — we hear the turntable arm lift off the record — and the sound of children in the distance is heard. Stan removes himself from his wife’s embrace, hesitates, and leaves the room. A snippet of a poem is read on the soundtrack, followed by a wash of classical music. The woman glances upon a pair of baby shoes, holds them to her breast, and exits our purview.

Stan is the hub around which events in “Killer of Sheep” revolve. He works at a slaughterhouse — Stan is the title character — and has had two children with his wife, Stan Jr. (Jack Drummond) and Angela (Angela Burnett). The family lives along a poverty-stricken row of houses at Watts, Los Angeles, though Stan is intent on bringing a sense of pride to their humble accommodations. When he’s not at his job, he’s scraping floors, fixing the sink, and otherwise attempting to bring the homestead up to snuff.

Does our protagonist ever sleep? Stan is driven by familial responsibility but also by a sense of dignity. We have to intuit as much, as he’s a man of few words. Mr. Burnett’s picture doesn’t concern itself with anything so concrete as a plot, concentrating, instead, on impressionistic vignettes of Black life circa 1972. We get to know the denizens of Stan’s neighborhood through an accumulation of moments. Evocation rather than explication is the rule.

Mr. Burnett made “Killer of Sheep” as a graduate student at UCLA. The film’s budget came in at $10,000 and it looks it: The gritty black-and-white cinematography and casual, sometimes clunky mise en scène are closer in tone to a documentary than fiction. Still, budgetary restraint is no indicator of aesthetic merit: Mr. Burnett brings to light a swatch of American life with a delicacy that makes the prototypical Italian neorealismo come off as so much showboating.

A lot of time is spent on establishing context; in an odd way, the entire film is context. We repeatedly watch a group of neighborhood kids amuse themselves in environments marked by neglect: empty lots filled with rubble and the hidden byways of abandoned buildings. Their pursuits are rough-and-tumble, and sometimes dangerous. Among the most memorable scenes is a line-up of adolescents leaping from rooftop to rooftop. Later, rocks are thrown in a mock battle and train tracks explored in ways that will likely cause conniptions for 21st-century helicopter parents.

An overriding air of resignation, a sense of long days and wayward temptations, is punctuated by narrative sidebars that are all-too-recognizable and often comic. In one instance, a day at the races with family and friends is upended because of a flat tire; in another, a long sought-after automobile engine meets an ignoble fate. All the while, Mr. Burnett reminds us of the dignity that can accrue from the most humble amongst us. “Killer of Sheep” is a deeply humane movie.