Air Travelers at Mercy of Homeland Security Department After Suspension of Two Security Screening Programs

By SHARON KEHNEMUI

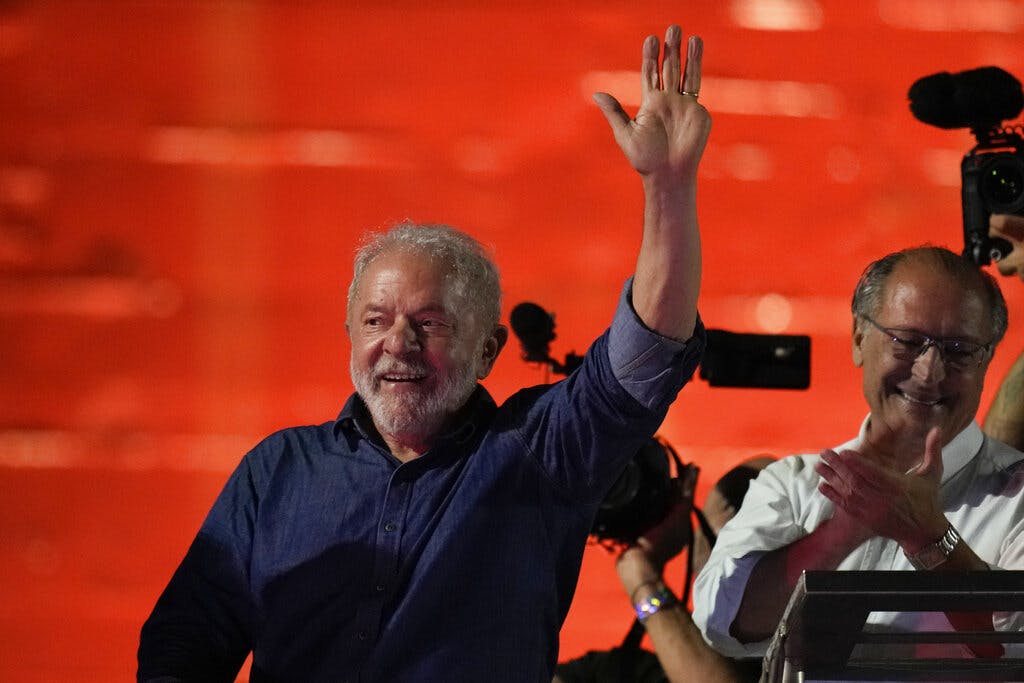

|Violence in the streets is widely feared as Bolsonaro waits — or refuses — to concede.

Already have a subscription? Sign in to continue reading

By SHARON KEHNEMUI

|

By NEWT GINGRICH

|

$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

By continuing you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.

By LENORE SKENAZY