Democrats, Once Masters of Messaging, See Trump Stealing Their Mojo With Colorful, Persuasive Branding

When rhetoric outlives its usefulness, wise politicians abandon it.

President Trump’s talent for colorful, persuasive branding is turning a strength of Democrats against them. The party’s support is ebbing, but it can recapture its mojo by applying the lessons of past success: Policies can’t be imposed on voters; they need to be sold.

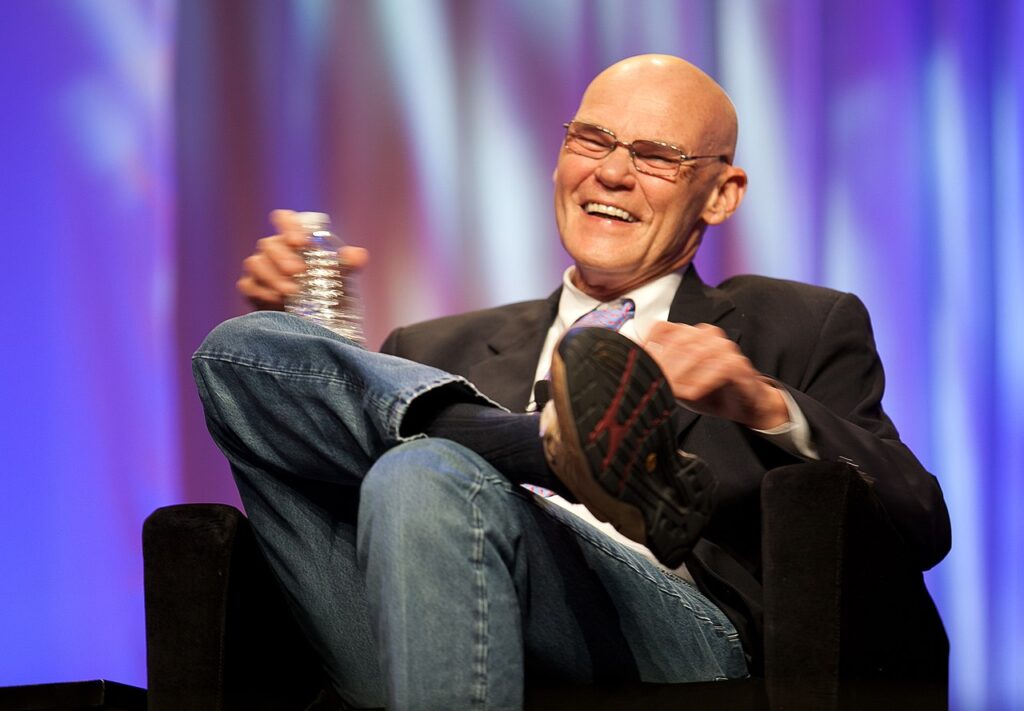

A Democratic political consultant, James Carville, helped President Clinton win the three-way race of 1992. That success, Mr. Carville reminded viewers in a Politicon video on Tuesday, was due to sharp messaging that brought Democrats in step with the country.

In 1988, President George H.W. Bush called Governor Dukakis “a Massachusetts liberal” because Americans rejected that ideology. It’s no coincidence that liberals soon began rebranding themselves as “progressives,” because the root word is “progress.”

What Republicans called “tax and spend,” Mr. Clinton called “investments.” Another of his strategists, Douglas Schoen, adopted the term “triangulation” to position the president as a moderate between the extremes of left and right, helping to win the president a second term.

AP/J. Scott Applewhite

Democrats succeeded in adapting their sales pitch in the 1990s. After the success of Presidents Reagan and Bush, they poll-tested everything from policy to where the Clintons vacationed to sync up with the electorate’s mood.

Mr. Clinton was packaged as a different kind of Democrat. It mirrored how a Hasbro executive, Donald Levine, sold G.I. Joe. Since playing with dolls was associated with girls, he coined the term “action figure,” doubling Hasbro’s market by understanding his target audience.

Mr. Carville wants the same re-evaluation of the Democratic lexicon today. On Tuesday, for example, he said promising “generational change” alienates older voters. Democrats can “use ‘equality’ to your little heart’s desire,” he said, but not “equity.”

People, in Mr. Carville’s view, can’t define or interpret “equity” or think it means “you tried to force an outcome.” He called “oligarch … another really stupid word” because it’s ill-defined. He proposed “fat cats,” because everybody “knows what a fat cat is.”

While there’s “nothing wrong with the word ‘community,’” Mr. Carville said, “it’s such a Democratic word,” and ought to be retired. He suggested avoiding “the ‘LBGQT+’ or whatever it is,” in favor of words “most commonly used among people as they talk to each other,” like “gay.”

In April, on his “Politics War Room” podcast, Mr. Carville bristled at phrases like “people of color,” calling them “racist,” because they lump all minorities together. He added that “no one uses the term ‘intersectionality’ except for NPR.”

In 1992, Democrats had lost three presidential elections in a row and five of the previous six. To win, they had to change how they spoke to the public. The new language didn’t mean abandoning hopes of moving the country leftward. They just overhauled their marketing.

When rhetoric outlives its usefulness, wise politicians abandon it. In the 2000 election, Vice President Gore criticized proposals by President George W. Bush as “risky schemes.” After Mr. Bush mocked the phrase in his acceptance speech at the GOP convention, Mr. Gore dropped the barb.

In 1817, President Van Buren — then just 17 — flipped another negative into a positive. When Federalists ridiculed his party as “bucktails,” meaning cowards who ran away like deer, he embraced the insult, telling supporters to pin bucktails to their hats. New York’s first political machine was born.

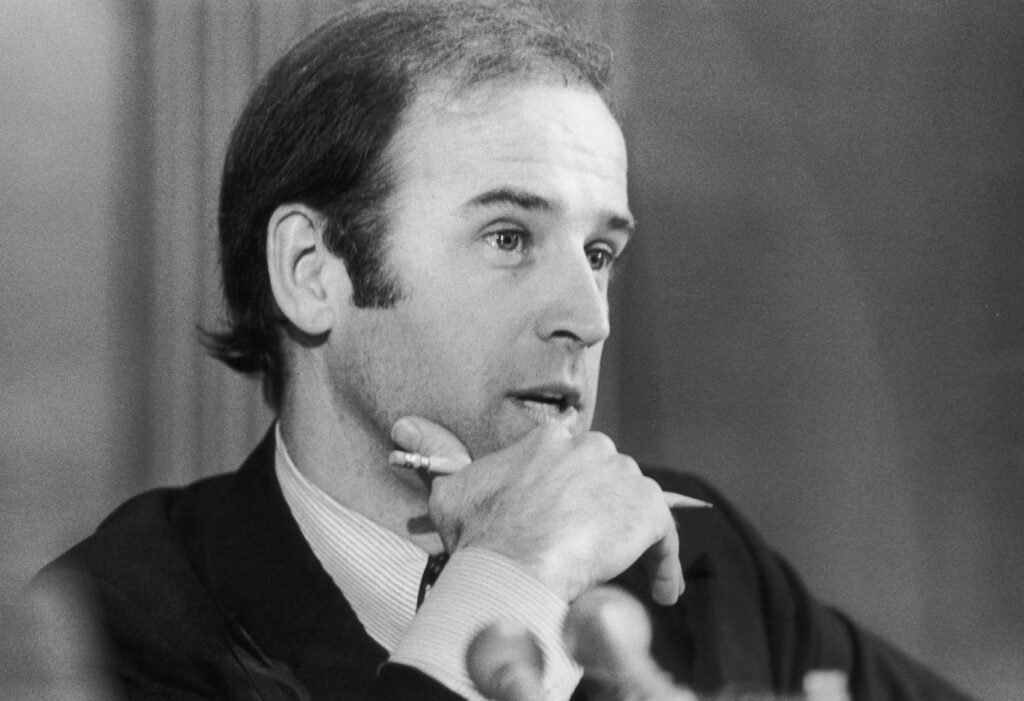

Branding is key in politics. The AP reported in 1973 that President Biden, then a freshman senator, “informed newsmen” that he’d “like them to refer to him” as “just Joe,” not Joseph. He spent half a century campaigning as “Amtrak Joe,” “Middle Class Joe,” and “Honest Joe.”

As a child, Senator Clinton promised to keep her maiden name but relented after it hurt Mr. Clinton’s career in Arkansas. A 2006 CNN poll found the reverse. Her positive rating increased by seven points among Republicans and six among independents when she went by Hillary Rodham Clinton.

Mr. Carville told Democrats on Politicon that they “have limited time” to make their case against Mr. Trump and supporters ought to “let them know” when their “language is not helpful.” The party can learn from his experience or keep trying to force voters to buy dolls when they’d be far more likely to play with action figures.