Discord in the ‘Courts of the Conqueror’ as Indian Law Case Splits the Nine

It is a story as old as the bloody conflicts over this land: What is the relationship between what the Supreme Court calls ‘Indian country’ and America’s federal and state governments?

It is a story as old as the bloody conflicts over this land: What is the relationship between what the Supreme Court calls “Indian country” and America’s federal and state governments?

The latest chapter dropped yesterday, in the waning days of this landmark term, and came in the form of a case called Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta. By a five-to-four margin, the Nine held that non-Indians accused of committing crimes against Indians on Indian lands will come under the jurisdiction of both federal and state courts.

The decision clawed back the ruling of McGirt v. Oklahoma, which held that crimes on tribal lands could be heard only by tribal or federal courts, not by their local or state counterparts. Both cases were decided by five-to-four margins, with the earlier one predating Justice Amy Coney Barret acceding to the high court.

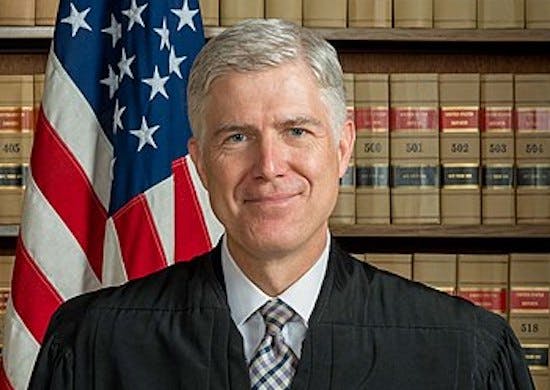

Justice Neal Gorsuch, who penned the majority in McGirt, here found himself authoring a scathing dissent, accusing the majority of “astonishing errors” and of generating “an embarrassing new entry into the anti-canon of Indian law.”

In acting to “hold the government to its word,” the McGirt majority found that the Cherokee nation reservation in the eastern part of Oklahoma had never been lawfully dissolved, and thus the territory, a full 43 percent of the state — encompassing Tulsa and including more than 2 million persons — remained Indian country.

Victor Castro-Huerta is a non-Indian convicted, along with his wife, of abusing his Cherokee stepdaughter. She was found “dehydrated, emaciated, and covered in lice and excrement” and weighing 19 pounds. There were “bedbugs and cockroaches” in her bed. Initially convicted in state court, that was tossed out after McGirt, and he was tried and found guilty in federal court.

All agree that the federal government’s jurisdiction extends to Indian lands, so the court turned its attention to “whether the State’s authority to prosecute crimes committed by non-Indians against Indians in Indian country has been preempted.”

That preemption can be achieved via conflict with a federal law, or if the state unduly infringes on tribal sovereignty. The question is made acute by the reality that without state jurisdiction, the federal government was struggling to keep apace with crime, as “the U. S. Department of Justice was opening only 22% and 31% of all felony referrals in the Eastern and Northern Districts of Oklahoma.”

The majority found that tribal self-government remained intact because “Indian tribes lack criminal jurisdiction to prosecute crimes committed by non-Indians such as Castro-Huerta, even when non-Indians commit crimes against Indians in Indian country.” If the only parties to the criminal case “are the State and the non-Indian defendant,” no tribal injury can be detected.

In dissent, Justice Gorsuch argued: “After the Cherokee’s exile to what became Oklahoma, the federal government promised the Tribe that it would remain forever free from interference by state authorities.” For him, only tribal or federal law can govern this Indian country.

“Where this Court once stood firm, today it wilts,” Justice Gorsuch writes, suggesting that the Nine have retreated from the notion that “even in the ‘Courts of the conqueror,’ the rule of law meant something.” Tribal reservations,” Justice Gorsuch writes, “are not glorified private campgrounds.”

Decrying “schemes to seize Indian lands and mineral rights by subterfuge,” the justice insists: “The real party in interest here isn’t Mr. Castro-Huerta but the Cherokee, a Tribe of 400,000 members with its own government.” Yet, he noted, they are not parties to the case.

When it comes to the interests of the Cherokee and the court’s holding, Justice Gorsuch writes that “a more ahistorical and mistaken statement of Indian law would be hard to fathom.”

By no means, though, do all conservatives agree with Justice Gorsuch. The Wall Street Journal, in the latest of a series of editorials on the crisis in Oklahoma, suggests that in Castro-Huerta the justices are beginning “to clean up their tribal McGirt mess.”