Documentary Casts a Topless Dancing Pioneer as ‘a Symbol of Empowerment’

‘Carol Doda Topless at The Condor’ is either the saddest movie to come down the pike in recent memory or a gauge of just how confused we are at this cultural moment.

“Carol Doda Topless at The Condor,” a documentary by Marlo McKenzie and Jonathan Parker, is either the saddest movie to come down the pike in recent memory or a gauge of just how confused we are at this cultural moment. The truth, you might assume, is somewhere in between, but this is a film that spends a lot of time skirting the truth, opting, instead, for a put-on-a-happy-face ambiguity. “Topless at The Condor” is a fascinating and dispiriting entertainment.

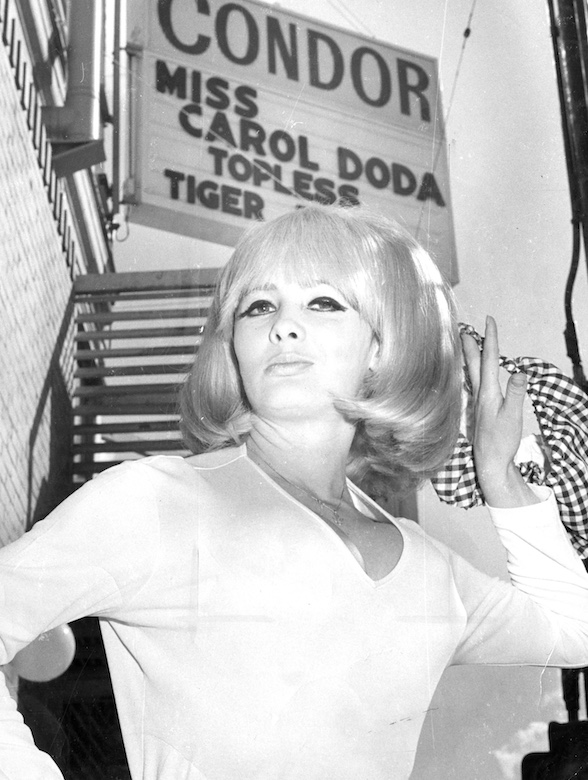

You wouldn’t know that from how the film is being marketed. “Every city has a history,” the poster reads, “San Francisco has a legend.” A vintage black-and-white photo of Carol Doda, the first stripper to go topless in these United States, is set against a backdrop of the Golden Gate Bridge and a row of nightclubs that once lined the city’s Broadway district. Within the fold of Doda’s arms is a collaged array of women holding up their bras, all of which are presumably intended for the nearest bonfire. The visual pun is that these first-wave feminists are nestled within Doda’s pre-feminist bosom.

Forget, for a moment, that one of the scholars featured in “Topless at the Condor” states that the phenomenon of bra burning was a media myth. Instead, consider how Doda is being heralded as “a symbol of empowerment.” The film’s website is downright chummy, being an accumulation of period kitsch, including a San Francisco timeline that includes the Gold Rush; the invention of sourdough bread; the first black woman millionaire, Mary Ellen Pleasant; and, of course, the release of this film.

Not much is known about Doda’s formative years: speculation about them runs in conflicting currents. Born in 1937, Doda was the child of divorce: Her parents separated when she was 3. At age 14, Doda was working as a cocktail waitress. At 26, she danced topless, having been encouraged by a publicist to don a “monokini.” Doda’s notoriety increased after attempts to ban topless dancing failed to pass the courts. And when she enlarged her breasts through a series of silicone injections? As Doda’s career proved, nothing succeeds like excess.

Tom Wolfe would go on to write about “The Put-Together Girl” and Doda appeared in the Monkees’ one-and-only movie, “Head” (1969). By that time, she had established her signature dance routine, predicating it on a song co-written by a young Sly Stone, “The Swim.” The trappings at the Condor were elaborate: Doda would enter the stage gyrating atop a grand piano that was lowered from a hole in the ceiling via a hydraulic lift. The crowds went wild.

But so, then, did life. Doda kept fairly mum about its details, though she intimated that her travels had been difficult. A raft of disappointing men, including Frank Sinatra, left their mark. Did she have children? Apparently so, though many of the interviewees in the film are shocked at the mention of the idea.

The 1960s took a turn toward the decade’s end — from the freewheeling inanities of Flower Power and the hard-won promises of the civil rights movement to societal tangents that were sectarian in character, morally expedient, and nihilistic in nature. The Summer of Love became less sunny. Is it at all a coincidence that Doda took up “bottomless” dancing in 1969?

Whatever charm or innocence Broadway may have had at one point in time was lost as the area became a haven for prostitution, drugs, gangsters, and pornography. The environs became grottier, the clientele shadier, and violence was on the upswing: a markedly suspicious death occurred on top of the same piano that served as Doda’s stage. A series of bad business decisions and dubious career moves on Doda’s part led to a loss of income and a diminution of fame. Age, too, brought its complications.

The archival footage we see of Doda — she died at age 78 in 2015 — is sometimes cogent, often cringe-inducing, and never as incisive or revealing as a dispassionate viewer might like it to be. In the end, this pioneer of empowerment comes off as a forlorn spirit caught up in forces not of her own making.

When we’re told that “modern women wouldn’t be where they are without her,” it’s worth pondering just how beneficent Doda’s not altogether happy example might be. It’s a question that is left unanswered as this lopsided and loving documentary comes to a close.