Can Trump ‘Nationalize’ Elections?

By THE NEW YORK SUN

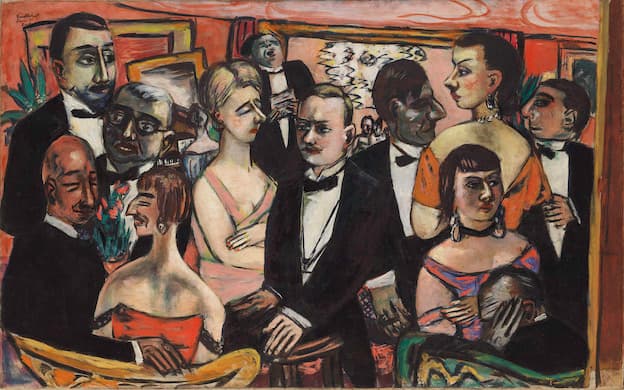

|After asking a friend why Beckmann’s bizarre imagery didn’t qualify him as a Surrealist, she responds immediately: ‘Because the world is too real for him.’ Exactly. Meet Max Beckmann, chronicler of times that are perpetually in crisis.

Already have a subscription? Sign in to continue reading

$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

By continuing you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.

By BRADLEY CORTRIGHT

|