Trump’s SOTU Unleashes America’s Golden Age of Growth

By LAWRENCE KUDLOW

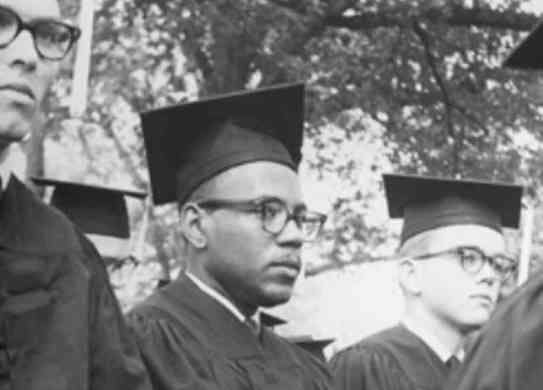

|As the first African American to enroll at the University of Mississippi, James Meredith was at the center of a struggle the depths of which even Faulkner did not fully imagine.

Already have a subscription? Sign in to continue reading

By LAWRENCE KUDLOW

|

By STEPHEN MOORE

|

$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

By continuing you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.

By A.R. HOFFMAN