Film Forum Goes High and Low in Gathering Films From the ‘Blaxploitation’ Era

As works of art, many of the pictures are dubious at best. The blessing of the genre is that it provided work for many deserving actors, some of whom have achieved measures of immortality.

‘Blaxploitation, Baby!’

Film Forum

August 16-22

By fairly general consensus, the soundtracks of “Blaxploitation” films have better weathered the passage of time than the pictures themselves. Forget Isaac Hayes’s indelible, Oscar-winning “Theme From Shaft” (1971) or the entirety of Curtis Mayfield’s album “Superfly” (1972); consider, instead, Willie Hutch’s “Give Me Some of That Good Old Love” from “Foxy Brown” (1974). Haven’t heard of it? A toe-tapper it is, and proof that even second-tier Blaxploitation music is worth your while.

Film Forum will be presenting a group of films dating largely from the genre’s heyday, the early 1970s, under the title “Blaxploitation, Baby!” Has this series been mounted as an air-conditioned antidote to the summer doldrums or as a response to “Black Caesars and Foxy Cleopatras: A History of Blaxploitation Cinema,” the recent book by Boston Globe film critic, Odie Henderson?

Whatever the case, there’s always an audience for, as the Museum of the Moving Image has taken to calling the genre, “disreputable cinema”: pictures that prompt tsk-tsking of one sort or another from polite society. Marginalia, you know: It’s where it’s at.

The genre of Blaxploitation followed on the heels of an era of social unrest and ideological partisanship, the 1960s. The films were made on the cheap and put the African American community front-and-center — not that everyone in the community was happy about it.

“Blaxploitation” was a pejorative coined by the then head of the Beverly Hills/Hollywood branch of the NAACP, Junius Griffin. “Superfly” (1972) was, in his estimation, “an insidious film that portrays the black community at its worst.” Cavils were made that the pictures glorified antisocial behavior and did so to the detriment of Black Americans. Gains in representation often came at the expense of ratifying existing stereotypes.

The ur-Blaxploitation film is Melvin Van Peebles’s “Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song” (1971). Made for $150,000, the picture ultimately took in more than $15 million. Its popularity expanded beyond the intended market and ushered in a new degree of creative liberty amongst African Americans.

Did the film provide a “viable, sexual, assertive, arrogant black male hero” for audiences weaned on the “asexual” politesse of Sidney Poitier, as was asserted by a film historian, Donald Bogle?

Like most political or artistic provocations, “Sweet Sweetback” hasn’t dated well. Forget the simmering arguments about its moral worth: As a film, Van Peebles’s opus is unbearable. Cinematic flourishes derived from the French New Wave have all the authority of an Austin Powers pastiche. The acting is atrocious. As the title character, Van Peebles’s performance is, let’s be charitable, pro forma.

The Library of Congress has dubbed Van Peebles’s film as “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant” — which it is, but primarily as a sociological artifact. As a work of art, it’s considerably more dubious.

The success of films like “Sweet Sweetback,” “Superfly,” “Shaft” (1971), and almost any picture featuring the statuesque Pam Grier proved there was a wide audience for such entertainments. As a consequence, the heads of major studios perked up and took notice. African Americans go to the movies: Who could have imagined such a thing?

Yet with success comes formula, and with formula, torpor. The blessing is that the genre provided work for deserving actors like Richard Roundtree, Moses Gunn, Yaphet Kotto, Lola Falana, Gloria Hendry, Scatman Crothers, Vonetta McGee, and Calvin Lockhart.

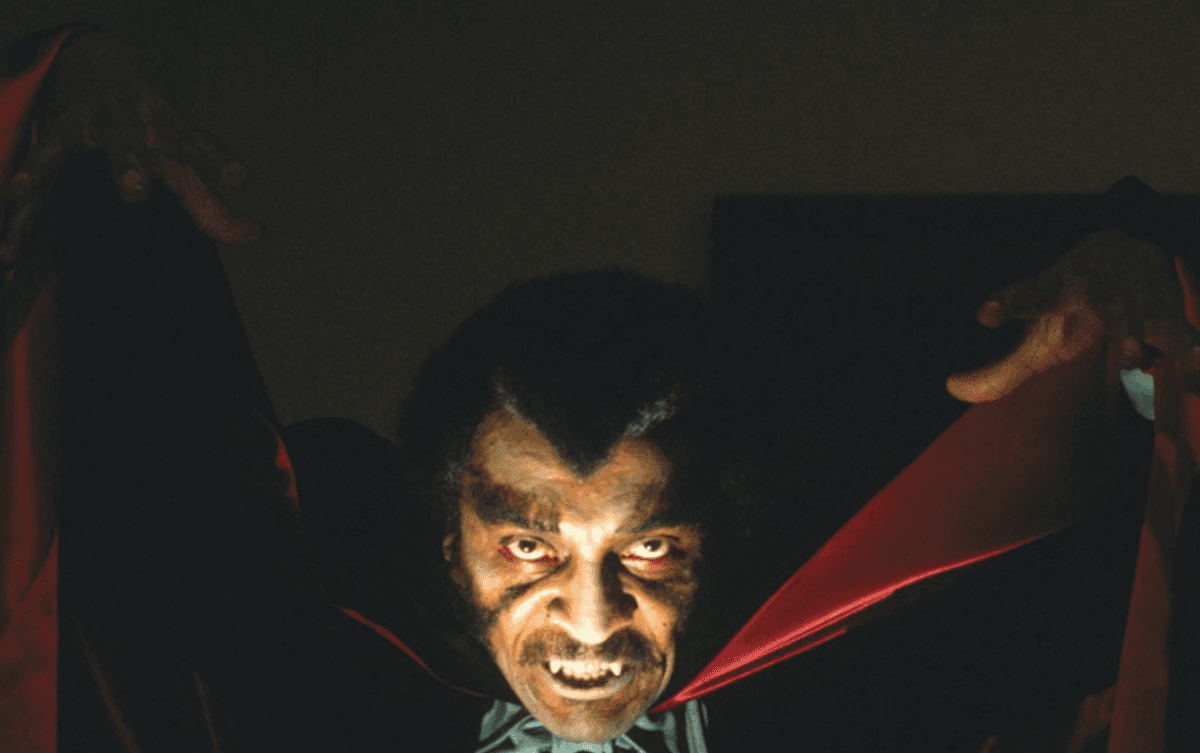

Among those who proved to be to the metier born — that is to say, acting — was William Marshall (1924-2003). A graduate of the Actors Studio versed in classical theater, Marshall lent his talents to two memorable horror films, “Blacula” (1972) and its sequel, “Scream Blacula Scream” (1973).

Although the sequel is nominally better than the original, both are powered and, in the end, redeemed by Marshall’s performances. No one bothered to tell him that these grindhouse entertainments weren’t “Hamlet”: Marshall brings presence, dignity, and depth to his take on an 18th-century African prince who had an unfortunate run-in with a certain count from Transylvania.

Immortality is a fickle thing. Marshall achieved it. That’s one reason a trip to Film Forum is warranted during these days of summer.