Film Forum Mounting Retrospective of a Filmmaker Whose Reputation Is Due for an Overhaul, René Clair

During the prime of his career, roughly between the late 1920s and the ’40s, Clair was held in high esteem by his peers, with Orson Welles dubbing him ‘a real master.’

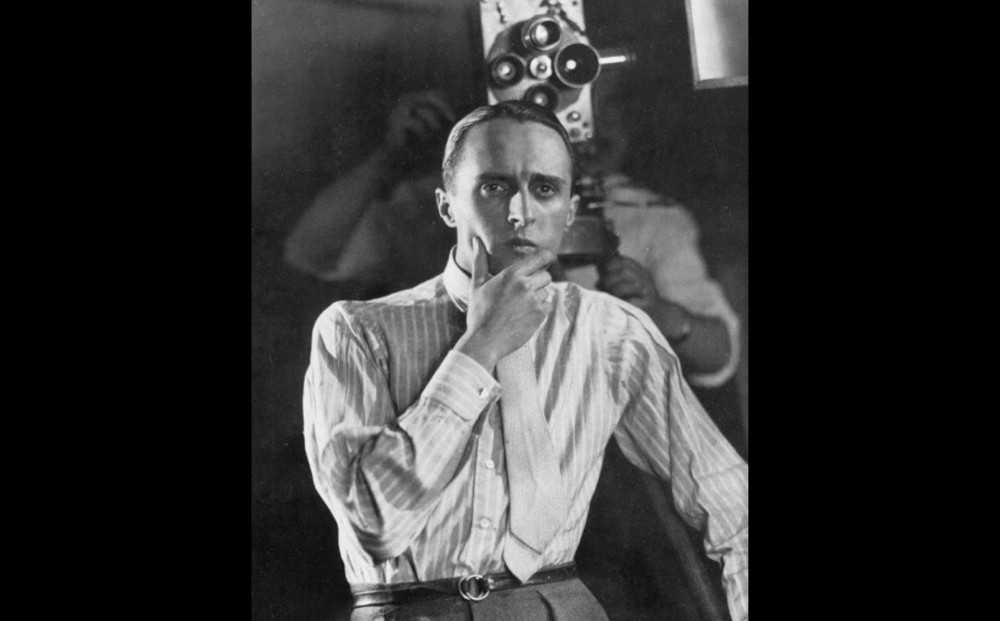

Has there been a filmmaker quite as winsome, as thoroughly knowing and wise, as René Clair (1898-1981)? During the prime of his career, roughly between the late 1920s and the ’40s, Clair was held in high esteem by his peers. Orson Welles dubbed him “a real master” and Charlie Chaplin thought the world of Clair’s “À Nous la Liberté” (1931) — so much so that when “Modern Times” came down the pike four years later, Clair’s production company sued for plagiarism.

Clair didn’t want any part of the lawsuit, though his demurral was pointed: “I know that Chaplin has seen ‘À Nous la Liberté.’ It is enough to look at his film.” Chaplin denied any knowledge of the Clair picture, but eventually agreed to an out-of-court settlement.

Moviegoers familiar with the exploits of the two jailbirds at the center of “À Nous la Liberté,” Émile (Henry Marchand) and Louis (Raymond Cordy), know the similarities that are shared with “Modern Times.” Those who aren’t can make their own comparisons at an upcoming two-week retrospective mounted by Film Forum, “René Clair.”

“Like many artists,” a poet and film critic, Michael Atkinson, wrote, “René Clair has been the victim of the canon wars.” Welles’s “real master” started taking hits in the early 1950s when critic François Truffaut, writing for the influential journal Cahiers du Cinéma, dismissed Clair as a maker of “films for old ladies who go to the cinema twice a year.”

Forgetting for a moment that old ladies can be just as discriminating as the nearest cineaste, Clair’s reputation has never recovered. If he’s mentioned at all nowadays it is usually done begrudgingly, with condescending nods directed at seminal pictures like “The Italian Straw Hat” (1928), “À Nous la Liberté,” and “Le Million” (1931). Clair’s dalliance with Dadaism — he worked with perpetual gadfly Francis Picabia on “Entr’acte” (1924) — scores points with those with a taste for nose-thumbing tomfoolery.

Clair’s subsequent turn to storytelling and, especially, Hollywood made him a figure of ill repute. The time this most French of directors spent in England and America is often cited as proof of the inherent corruptibility of commercial accommodation. There’s some truth to the claim, but if films like “The Ghost Goes West” (1935) and “And Then There Were None” (1945) aren’t as epochal as Clair’s earlier work, they are more than merely charming, being imbued with a poetic mien that is decidedly continental.

Would it take an effort of will for a contemporary viewer to connect with “Le Million“? Its tale of a starving artist, a wayward jacket, and a winning lottery ticket is a frothy movie untouched by anything resembling reality. Its musical trappings may strike some as dated, but the story’s trajectory is gutsy: Clair begins with a happy ending and circles back to it, all the while retaining suspense and comedic tension. A buoyant ensemble piece, “Le Million” is a reminder that while life may be short and chaotic, it can also be filled with joy.

“À Nous la Liberté” is a comedy of sharp observations, an operetta that doesn’t elicit laughter so much as moments of recognition — about social stratum, men and women, men and men, and the ironies attendant to a life lived well if not always honestly. The film’s artifice is clear, and its politics simultaneously obvious and flighty: Criticisms of Clair’s naivete gain some credence here. Yet once the picture hits a groove you’ll forgive its philosophical shortcomings. All the while, Clair employs sound — a new technology at the time — in a manner that can still take one aback.

Clair’s finest English-language film is likely “I Married a Witch” (1942), in which the fantastic and the droll are ladled out in equal dollops. Mention should be made of the precursor to “Groundhog Day” (1993), “It Happened Tomorrow.” Clair went on to pooh-pooh this light-as-a-feather fantasy, but you’ll likely find yourself smitten by a game cast, otherworldly portents, and an auteur incapable of faking it even as he was cashing a check.

Clair in 1947 returned to France, where he made a handful of films and managed to gain back some of his credibility. Of particular interest during this period is his initial foray into color, “The Grand Manoeuvre” (1955). Clair’s shuttling of characters through the paces of a traditional story of romantic comeuppance is cunningly conceived, even if the plot doesn’t sting as much as it could. Michèle Morgan brings grit and nuance to a role that might have otherwise been too pat by half.

Clair’s later phase deserves greater critical appraisal — but, then, so too, now, does his entire oeuvre. Wit and delight are worth their weight in angst and avant-gardism. If sophisticated denizens of the 21st century aren’t able to relish Clair’s vision, that says more about the shortcomings of our age than it does about the ineluctable grace of this generous filmmaker. “René Clair” is a must see.