Film Forum Screening ‘Who Killed Teddy Bear,’ What It Calls ‘the Apex of Lurid ’60s Exploitation Movies’

Welcome to Manhattan circa 1960, a black-and-white slurry of low-rent apartments, low-class businessmen, movie theaters exhibiting dubious fare, and bookstores that trade in girlie magazines.

The cineastes at Film Forum are doing a hard sell for Joseph Cates’s “Who Killed Teddy Bear” (1965). Cates’s picture, we are told, is “the apex of lurid ’60s exploitation movies” and “seething with a sweatily frustrated libidinousness.” Sounds juicy: How could a film that was busy “shattering every Hollywood taboo in the book” not be? Amongst all the heavy breathing, the rarely deployed adjective “caressingly” is put to use and there are references to pornography, lesbian clubs, and a scantily clad disco dancer. Pretty hot stuff for a Jan Murray movie.

Would it be fair to say that Murray is nowadays remembered primarily by comedy nerds and boomers who spent their formative years watching too much daytime television? Born in the Bronx, Murray exhibited an early flair for getting laughs, got his sea legs in vaudeville, honed his craft at the Borscht Belt, and became a headliner in Las Vegas. He held sway on any number of game shows, popped up as a guest star on various television programs, and for 18 years was the host of the West Coast Chabad Lubavitch telethon. He died in 2006 at the age of 89.

Murray isn’t the star of “Who Killed Teddy Bear” — his name comes third in the credits — and he’s certainly not the reason Cates’s film has gained a cult following. While men of a certain age may perk up at the mention of Juliet Prowse, a vivacious dancer who no less an authority than the Washington Post claimed had “the best legs since Betty Grable,” it is the presence of Sal Mineo (1939-76) that, in significant part, cemented the movie’s slim purchase on posterity.

Like Murray, Mineo was a child of the Bronx, born to Italian emigres who earned their keep as coffin-makers. Josephine Mineo enrolled her son in acting classes and Sal went on to perform in stage productions alongside Maureen Stapleton, Eli Wallach, and Yul Brynner. Mineo’s breakout role, as a doe-eyed teenager desperately enamored of James Dean’s title character in Nicolas Ray’s “Rebel Without A Cause” (1955), earned him his first Oscar nomination. “The first gay teenager in films,” as Mineo described his character, Plato, continues to strike a chord with audiences.

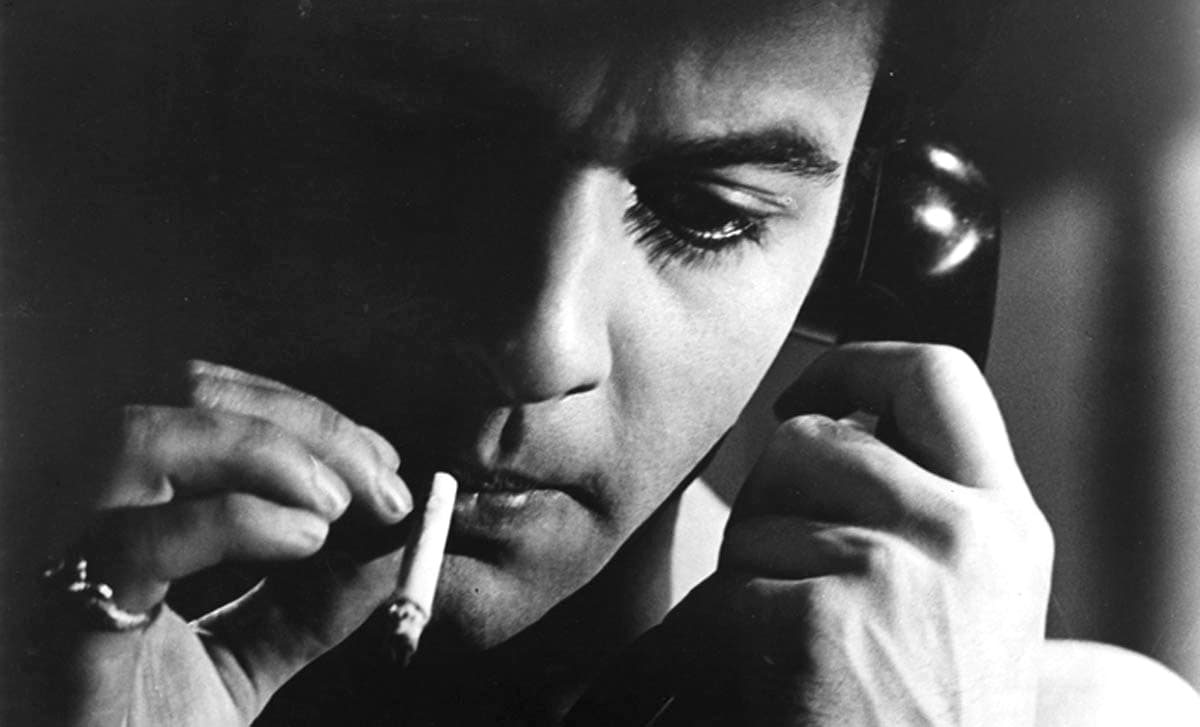

Subsequently typecast as a forlorn adolescent, Mineo soldiered on, hoping to widen his choice of roles even as age caught up with him. Taking on the part of a villain in Cates’s on-the-cheap noir was a gamble: Not only did Mineo play against type, but the role keyed into an unseemly species of sexuality. We first glimpse the actor — or, at least, his body double — striking a range of provocative poses wearing nothing but his tighty-whities. Imagine Bruce Weber’s hunky Calvin Klein ads somehow rendered more lurid.

Welcome to Manhattan circa 1960, a black-and-white slurry of low-rent apartments, low-class businessmen, movie theaters exhibiting dubious fare, and bookstores that trade in girlie magazines, the Kama Sutra, and “Naked Lunch” by William Burroughs. Within this milieu lives Norah (Prowse), an aspiring actress working as a disc jockey in a nightclub overseen by Marian Freeman (Broadway stalwart Elaine Stritch). Among Norah’s co-workers is a waiter, Lawrence Sherman (Mineo), whose primary responsibility in life is taking care of his disabled 19-year old sister, Edie (Margot Bennett). A charitable sort, our Larry, but he’s prone to his own set of demons.

Norah is on the receiving end of a host of obscene phone calls, and when a decapitated teddy bear is left on her bed she calls the police. Enter Lieutenant Dave Madden (Murray), whose interest in Norah’s safety takes some weird turns — New York’s finest, he decidedly ain’t. There’s more back-and-forthing between all involved, some of it ugly indeed. All of which cries out for a director with a deft hand for navigating the dingier byways of the human psyche — Alfred Hitchcock, say, or Claude Chabrol. Cates is capable when he wants to be but almost fatally bereft of wit or cunning.

“Who Killed Teddy Bear” does have its own tawdry kind of integrity, but it’s best sampled by those for whom cinema’s illicit promises are better in theory than in practice.