Can Trump ‘Nationalize’ Elections?

By THE NEW YORK SUN

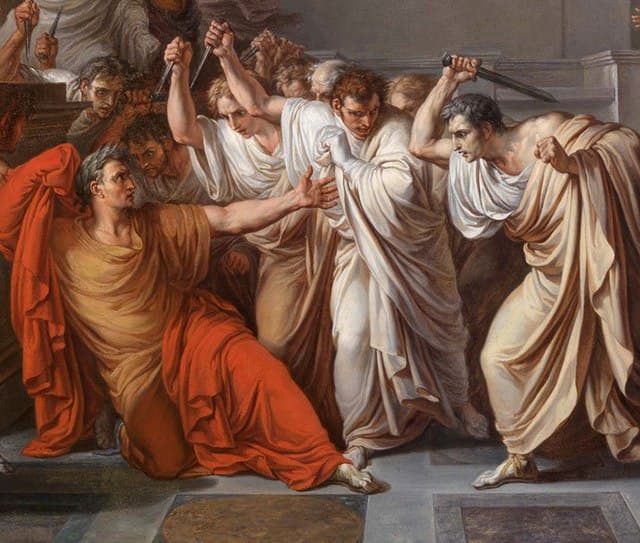

|Mary Beard offers a most helpful roadmap of the empire’s main players, while Ferdinand Mount avers that the possibility that any society may succumb to Caesarism is, well, very real.

Already have a subscription? Sign in to continue reading

$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

By continuing you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.

By BRADLEY CORTRIGHT

|