Going Gothic With Richard III and William Faulkner

The desire to turn real people into fictional characters disturbs those who want to draw a firm line between fiction and fact. It can’t be done — not in a novel, and not in works of history and biography.

‘The Princes in the Tower: Solving History’s Greatest Cold Case’

By Philippa Langley

Pegasus Books, 496 pages

‘Southern Light, Oxford Mississippi, A Novel’

By Eileen Saint Lauren

Eileen Saint Lauren Books, 264 pages

Could there be a better title for a Gothic novel than “The Princes in the Tower?” Two boys, one about to be crowned king of England, disappear in the Tower of London. Their uncle Richard is crowned king after they have been declared bastards. A few years later the Plantagenet monarch dies on Bosworth field, and his Tudor successor, Henry VII, presides over a reign in which Richard III is presumed to have had the princes “put to the sword,” as one account announced.

But wait: Other reports say the boys were drowned in Malmsey wine, poisoned, or smothered between two featherbeds. It all begins to seem fictional, with other suspected assassins, and it is also reported that the boys were not killed at all but exiled.

Historians have debated Richard’s culpability and the fate of the princes for hundreds of years, and this latest effort reads like a police procedural — as if the author-detective has also taken a graduate course in historiography.

Philippa Langley’s book is a forensic evaluation of the evidence. I won’t give away her conclusions, except to say the “Solving” in the book’s title does not mean the cold case has been cracked. Rather, “solving” is about the process of investigation, which, as Ms. Langley emphasizes, is not over — or as Sherlock Holmes would say, “Come Watson! The Game is Afoot.”

“The Princes in the Tower” is not the first effort to turn their fate into a detective story. That honor goes to Joseph Tey’s “The Daughter of Time,” in which Inspector Alan Grant ridicules credulous historians who pass on tradition as though it were fact. He goes too far in exonerating Richard, but that is a story for another day.

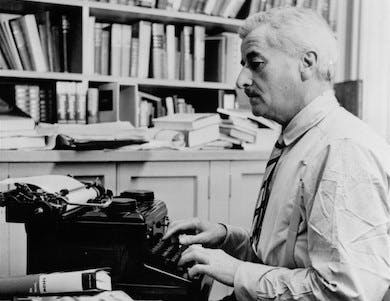

Faulkner has often been called a master of Southern Gothic, a term the author of “Southern Light” embraces with brio. She has a concluding section with suggestions about how to teach her work as a Gothic novel. As expected in the genre, you have ghosts — in this case a Confederate one, of course.

Faulkner’s greatest Gothic novel is “Absalom, Absalom!” It features a Southern scion, Quentin Compson, who is described as a “barracks indeed, filled with stubborn back-looking ghosts.” Virtually from the first page of “Southern Light,” we are on the way to Oxford, Mississippi, for a rendezvous with Faulkner, who becomes part of a story as haunted as his own fiction.

In Faulkner’s “Requiem for a Nun,” the narrator predicts that even as the modern South obliterates the physical remnants of its past, the urge to reclaim its history will become all the stronger. Now Faulkner turns up in a novel with its own idiot, as in “The Sound and the Fury,” and a haunted house, as in “Absalom, Absalom!” — which does, by the way, have a scion/prince who might as well be discovered in a tower.

Readers of biography and history may resist the Gothic thrust of “Southern Light,” preferring to stick with the Faulkner of fact. But biographies, no matter how vivid they are, tend to immobilize their subjects. After all, in a biography Faulkner cannot say new things. It is not allowed. In “Southern Light,” however, he can be neighborly, befriend a retarded boy, and drink Scotch while the boy’s mother confesses to a terrible crime that is perfectly Southern Gothic.

Like it or not, with Richard III or William Faulkner, their lives have become the stuff of fiction, and even if Faulkner drinks Scotch in this novel instead of what he might have preferred (Jack Daniels), that is what Faulkner is offered and between Scotch and nothing he will take Scotch.

This desire to turn real people into fictional characters disturbs those who want to draw a firm line between fiction and fact. It can’t be done — not in a novel, and not in works of history and biography. I’m reminded of what E.L. Doctorow said after the publication of “Ragtime,” when he was asked, “Did Evelyn Nesbit and Emma Goldman really meet?” Doctorow answered: “They have now.”

Mr. Rollyson published “The Re-creation of the Past in ‘Absalom, Absalom!’ in Mississippi Quarterly (summer 1976) and “The Detective as Historian: Josephine Tey’s The Daughter of Time,” in the Iowa State Journal of Research (August 1978).