Harris Vows America Will Stand With the Philippines

The vice president visits a front-line sandbar in the South China Sea.

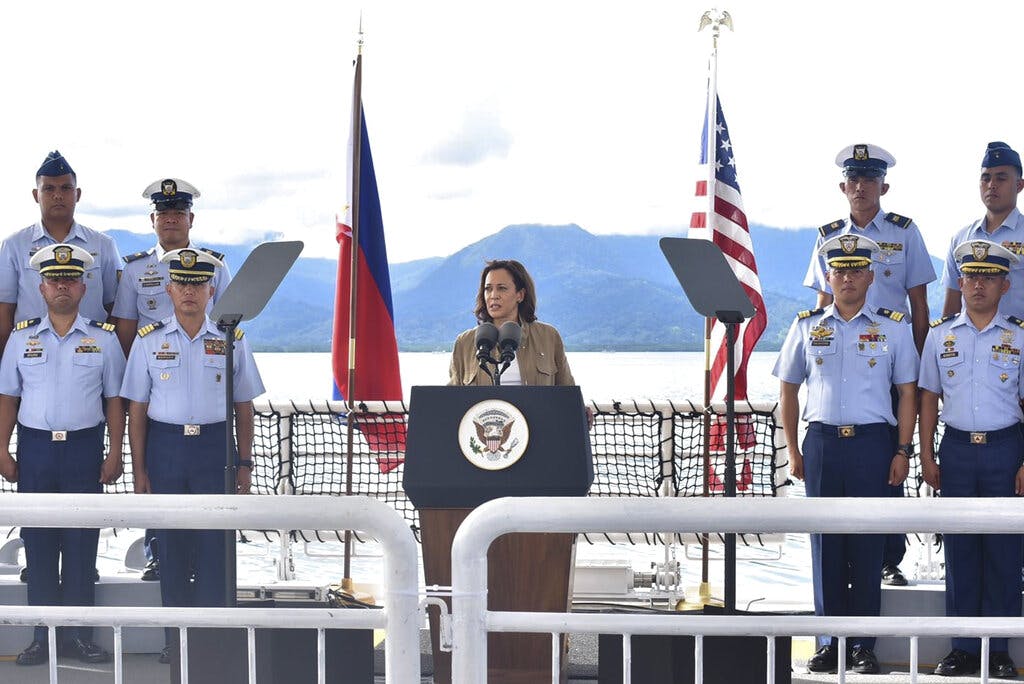

Vice President Harris, bringing American policy toward the Philippines full circle, has become the highest-ranking American official to visit Palawan — a long, strategic island that is on the front sandbar, so to speak, of the South China Sea as the communist regime expands into its vast waters.

Mrs. Harris took the occasion Tuesday to talk to fishermen and officials about China’s encroachment nearby. The vice president accused the People’s Republic of “unlawful and irresponsible behavior.” She described herself as standing with the Philippines “in the face of intimidation and coercion.”

The vice president also described as “legally binding” a decision of a United Nations tribunal in the Hague six years ago to dismiss China’s claim to the sea. The communists have been building bases on artificial islands dotting the South China Sea while the Philippines maintains a tenuous hold on several islands of its own.

Mrs. Harris’s visit dramatizes the shift in Philippine-American ties under the new president, Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. His predecessor, Rodrigo Duterte, downplayed and discouraged the historic Philippine-American alliance while appealing to China’s president for friendship and cooperation.

Back in 1986 the White House under President Reagan facilitated the downfall of Mr. Marcos Jr.’s father after 18 years of rule. Mrs. Harris met Monday with the new president in the storied Malacanang Palace at Manila, where she pleaded the American case for reviving once-close military relations.

Washington’s commitment was “unwavering,” Mrs. Harris assured Mr. Marcos Jr., 36 years after Marcos Sr. and his wife, Imelda, along with Bongbong and his two sisters plus family cronies, were forced to flee Malacanang via Yank helicopters. They were flown to Clark Air Base, then in American hands, and on to Hawaii on two Air Force planes.

To a history professor at the University of Wisconsin who has written extensively about the Philippines, Alfred McCoy, the shift in American policy is an exercise in “realpolitik.” While “presidents and principles come and go, geopolitics never change,” he told the Sun, “If flattery gets access to Philippines bases, the vice president must swallow principle and say whatever must be said.”

Ms. Harris did not have to remind Mr. Marcos Jr. of the bonds formed during more than four decades of American colonial rule after the Americans drove out the Spanish in 1898 and then defeated Philippine revolutionaries in 1901. Nor did she need to refer to the disgrace that befell his father.

“The U.S. has a long and deep history with the Marcoses, and all it took was for one of them to get back in power to rekindle the romance,” a veteran journalist with Human Rights Watch in the Philippines, Carlos Conde, said. “Marcos has a lot to gain by making sure that the U.S. is on his side, while the U.S. finds in him a great ally as it confronts China in the South China Sea.”

Not that “human rights” in broad terms was not on the agenda. Washington, Mr. Conde said, had been “less than enthusiastic in confronting the previous Duterte regime” but now sees in Mr. Marcos Jr. “an opportunity to press its key issues, among them rule of law, democracy, and human rights.”

Mrs. Harris, in Manila after addressing the Asia-Pacific Economic Community at Bangkok, avoided dilating on Marcos Sr., whose tyranny led to the revolution that enabled the rise of Corazon Aquino. She took over two and a half years after the assassination of her husband, Benigno Aquino, Marcos’s arch enemy. A former senator, he was gunned down getting off the plane returning him from self-exile in America.

Mr. Marcos Jr., in his meeting with Mrs. Harris, seemed anxious to improve relations. The Americans maintained two of their largest overseas bases, Clark, north of Manila, and the naval base at Olongapo to the west on the South China Sea, until the Philippine Senate in 1991 refused to extend the bases agreement.

American and Philippine forces have been staging annual military exercises ever since. At the same time, Mr. Marcos Jr., in his conversation with Mrs. Harris, also evinced a desire not to offend the Chinese. Carefully, he said he did not see “a future for the Philippines that does not include the United States.”

Mrs. Harris, working from the White House script, assured him of “defense of international rules and norms as it relates to the South China Sea.” America, she promised, would “invoke U.S. mutual defense commitments” in response to an “armed attack on Philippine armed forces, vessels, or aircraft.”

Nice words, but how much do they mean? Mr. Marcos and President Xi, in Bangkok for the APEC forum, assured one another that differences on the sea “do not define the totality of Philippine-China relations.”