Hodler, Cut From Symbolist Cloth, Gets at New York a Show of Depth, the First in Nearly 20 Years

Fans of Egon Schiele, our critic predicts, will thrill to the drawings up at the Morgan.

Ferdinand Hodler: Drawings — Selections from the Musée Jenisch Vevey

Morgan Library & Museum

Through October 1, 2023

Here’s a not-so-rash prediction: those enamored of the paintings and drawings of the doomed Austrian Expressionist Egon Schiele will enjoy “Ferdinand Hodler: Drawings — Selections from the Musée Jenisch Vevey” at the Morgan Library & Museum. Schiele and Hodler are, if not peas in a pod, then cut from a similar bolt of Symbolist cloth.

The Morgan show is the first time in close to 20 years that the Swiss painter has been seen in any depth in New York City. “Ferdinand Hodler: Views & Visions,” mounted in 1995 by the National Academy Museum, was a concerted attempt to place Hodler (1853-1918) firmly in the canon, as a vital link in a chain that includes contemporaries like Paul Gauguin, Edvard Munch, and Gustav Klimt.

Though the stray Hodler has been on display here-and-there, the self-appointed master of “parallelism” is, on the whole, obscure on these shores.

The exhibit at the Morgan is unlikely to increase Hodler’s cachet outside of his native country, but it’s not at all a bad round-up. Culled from the holdings of the Musée Jenisch at Vevey, a town on the shore of Lake Geneva, the show focuses primarily on works-on-paper — the Morgan’s calling card. The sixty pieces on view represent, roughly speaking, a tenth of the bequest of artist Rudolf Schindler, a Hodler collection outnumbered only by the Kunsthaus Zurich and Geneva’s Musee d’art d’histoire.

Ferdinand Hodler was born into modest means. His father was a carpenter, his mother a peasant, and his step-father, Jean Hodler, having died when Ferdinand was eight years old, a decorative painter. After Marguerite Hodler died of tuberculosis, Ferdinand went to study with a commercial artist who supplied the tourist trade with Alpine landscapes.

As Hodler matured, he felt increasingly hemmed in by the conservatism of his countrymen. “My goal remains Paris,” Hodler wrote in 1891. “The German Swiss will not understand me until they see that I have been understood elsewhere; also, only then will I impress the French Swiss.”

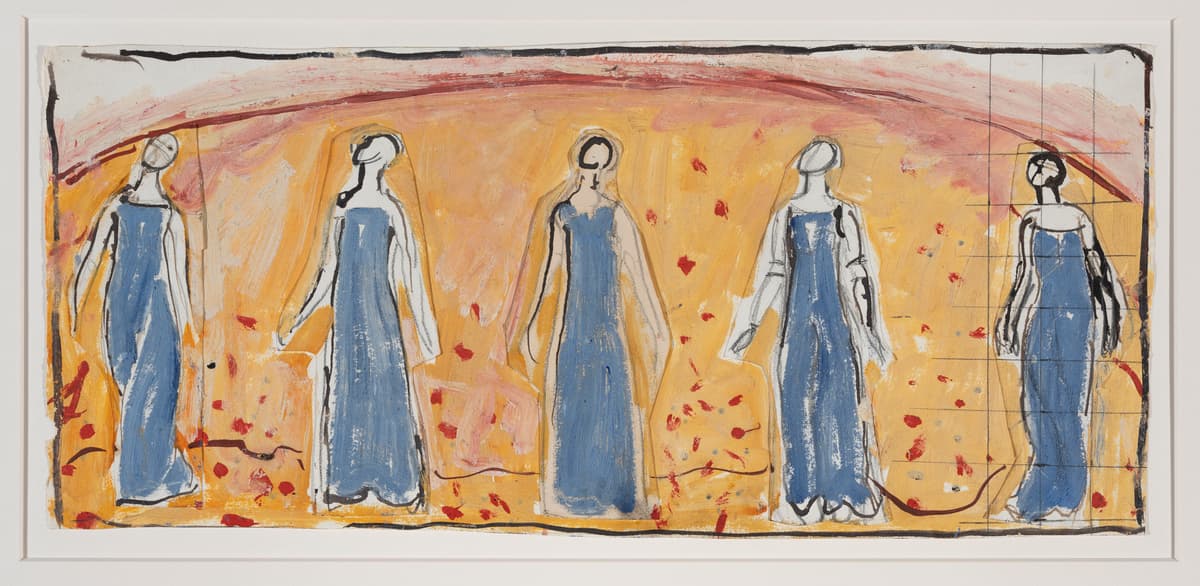

“Parallelism” was Hodler’s attempt to merge the decorative strategies of Art Nouveau with the spiritual currents of Symbolism. “Night” (1891), a highly choreographed tableaux tapping into Classical precedent, is the textbook example of his ambitions and, not coincidentally, the best-known of the pictures. Though there’s nothing on that scale at the Morgan, the sampling of preparatory drawings and paintings gives a good sense of the diligence with which Hodler approached a project.

Diligence, I would insist, and not obsession. The museum’s Acquavella Curator of Modern and Contemporary Drawings, Isabelle Dervaux, likens Hodler’s “search for the true form” to those of Ingres and Degas, but pegging artistic duty as “obsessive” is to superimpose contemporary mores onto historical models. The notion of obsession has become increasingly misconstrued as a marker of dedication. True obsession is something altogether different. Did Ms. Dervaux take a gander at Jean-Jacques Lequeu’s drawings, the subject of an unnerving exhibition at the Morgan in 2020? Now those were obsessive.

Disagreements about nomenclature aside, Ms. Dervaux is wise to Hodler’s “liveliness and immediacy” as a draftsman in contrast to the “contrived and artificial” character of his canvases. Though “Portrait of Berthe Hodler-Jacques” (ca. 1898) is a fine painting, the Hodler canvases at the Morgan evince an artist prone to overly dramatic stylizations and crabby paint-handling. The drawings, even those that are considerably involved, retain the vivacity of open exploration.

Hodler’s spindly line is his closest link to Schiele, along with the habit of having models strike inelegant poses. But there are correspondences, as well, with Klimt and, in a handful of surprising forays into collage, Matisse.

Although a progenitor of Modernism, Hodler remained steadfastly 19th-century in temperament which goes some way in explaining the ungainly nature of his art. All the same, “Selections from the Musée Jenisch Vevey” shines a diverting light on an odd and uncompromising artist.