Airports Promote Food Banks, Gift Cards for Unpaid TSA Workers as Spring Break Begins

By DAVID JONES

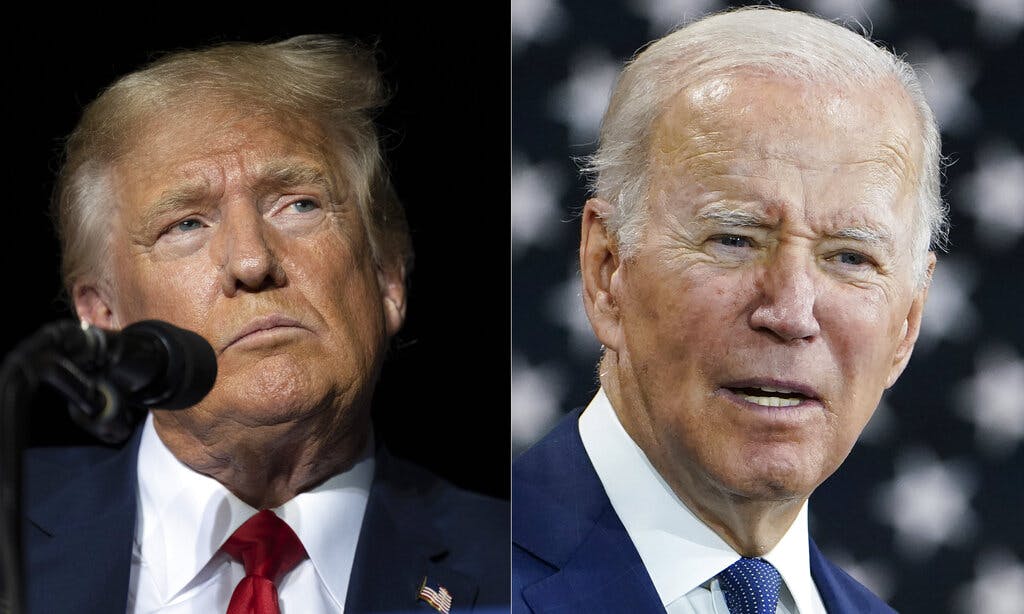

|American presidential politics has been characterized by a conviction that the other side isn’t merely misguided but criminally corrupt.

Already have a subscription? Sign in to continue reading

By DAVID JONES

|

By LUKE FUNK

|

$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

By continuing you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.

By BRADLEY CORTRIGHT

|