How Elvis Presley, the ‘King’ of Rock, Helped Forge a ‘New Kind of Country Music’

It took the likes of Emmylou Harris, Rosanne Cash, and a lot more singers and musicians singing and playing country music a different way.

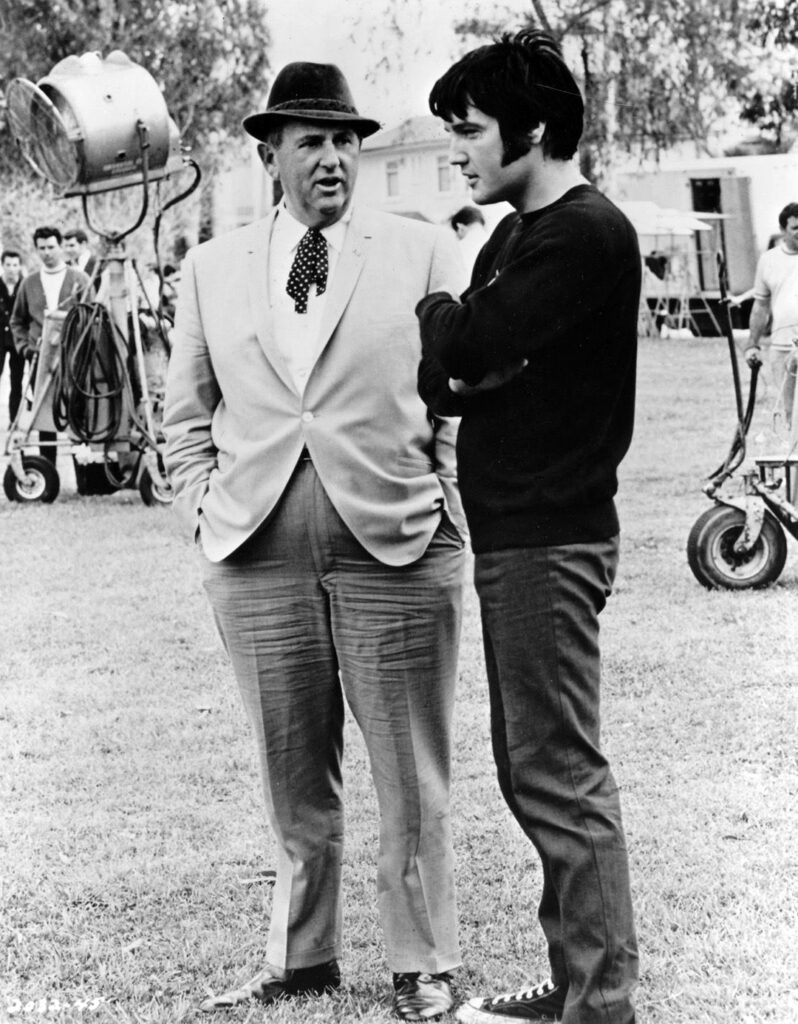

‘Elvis and the Colonel: An Insider’s Look at the Most Legendary Partnership in Show Business’

By Greg McDonald and Marshall Terrill

St. Martin’s Press, 384 Pages

‘In-Law Country: How Emmylou Harris, Rosanne Cash, and Their Circle Fashioned a New Kind of Country Music, 1968-1985’

By Geoffrey Hines

University of Illinois Press, 384 Pages

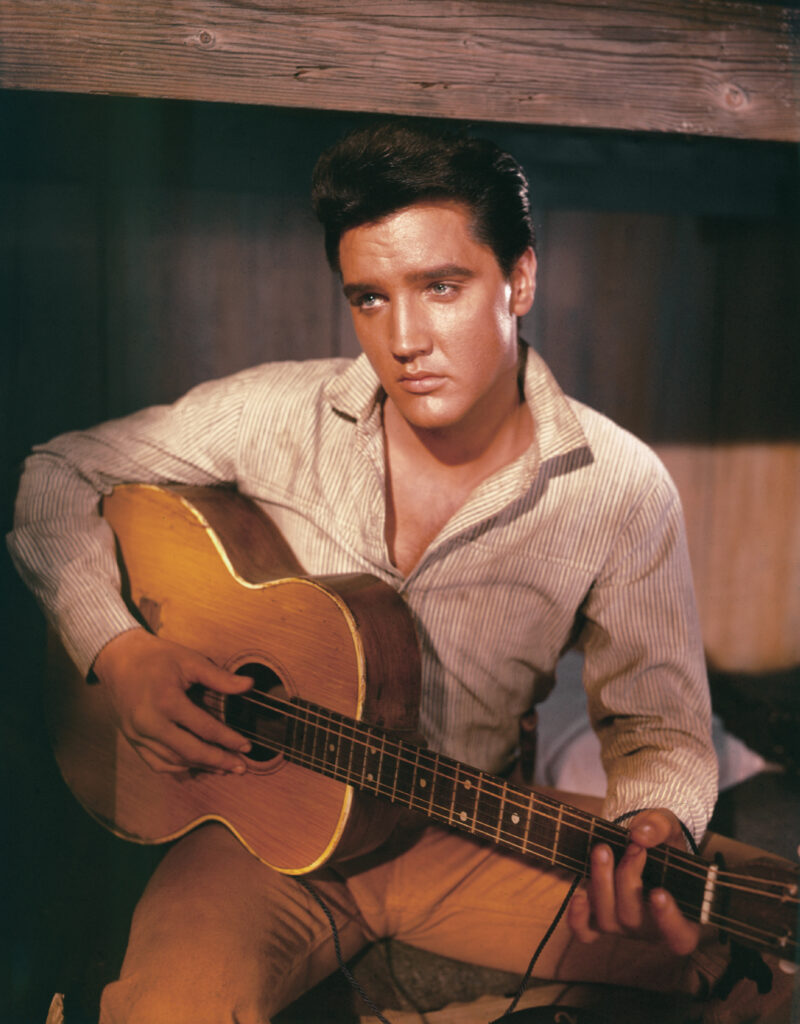

Although Elvis Presley is the king of rock and roll, before it became something else called rock, he might be credited with creating a new kind of country music, though it took the likes of Emmylou Harris, Rosanne Cash, and, actually, a lot more singers and musicians singing and playing country music a different way that delighted younger audiences and disturbed some old timers.

Geoffrey Hines’s narrative is congested with constant lists of innovators — all of whom are probably well known to aficionados but remain opaque to us casual listeners. “In-Law Country” is a sort of insiders’ guide, so that you have to pry open the story, so to speak, and also wait for several chapters for the principals to show up.

With so many interlocking marriages, and musicians switching from one group to another, and entering and exiting the narrative at many different points, “In-Law Country” would have benefited from some charts, tracking the intricacies of the way the new sound was created. Chapter titles don’t help much, except to keep the chronology straight.

Mr. Hines does provide some key markers, though, of the new kind of country music: “rootedness in the country-folk tradition, a skepticism toward modern America, and storytelling centered on someone who’s married, not single.” Women emerge as vital forces, not willing to simply stand by their men, and in the studio women became an active part in the composition and orchestration of the music.

The old stalwarts of country music, skeptical of rock-influenced new musicians and singers, were not impressed with groups like The Bryds, who tried in vain to win over Grand Ole Opry audiences. Other groups had more success in hiring musicians who had worked with Presley, going all the way back to his country rock days when he recorded “Blue Moon of Kentucky,” a “hopped-up version of a Bill Monroe bluegrass standard.”

Ms. Harris is the standout artist in this book, as she came to the new kind of country music from scratch, not having the lineage that helped Ms. Cash. Ms. Harris, after some tentative, nervous starts, quickly dominated the scene with her beautiful voice and appearance, collaborating as an equal with her male partners. Both Ms. Harris and Ms. Cash introduced to country music a gritty rendition of the working and love lives of married women.

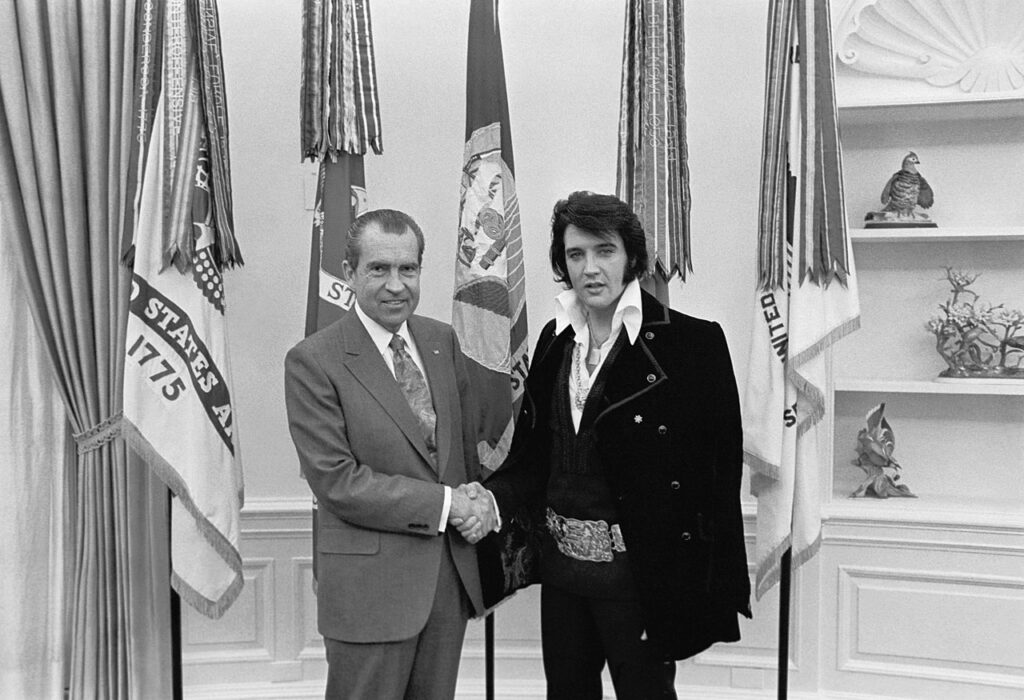

It is hard to see how any of this “new kind of country music” could have won over audiences without Presley’s example, abetted by the notorious Colonel Tom Parker, who, according to Greg McDonald and Marshall Terrill, has been much misunderstood:

“Colonel Tom Parker has gone down in history as a malevolent leech, the Svengali-like, cigar-chomping, ironfisted manager of the King of Rock ’n’ Roll. That’s the myth … the man he, in fact, wanted the world to see. He chose to play the heavy when the situation called for that. ‘The artist always wears the white hat,’ Parker said more times than I care to remember,” Mr. McDonald reports.

It was all an act, Mr. McDonald insists, with the Colonel a better actor than Presley. The Colonel had to play the heavy because of having to “do battle with businessmen, bean counters, and lawyers who had Ivy League backgrounds and lots of credentials hanging on their walls.” It is certainly true that many generations of performers in the music business have been cheated out of a lot of money by unscrupulous producers so that the Colonel offered himself as the one person Presley could always rely on.

Okay, but what about all those bad movies that wasted Presley’s talent? The director of “Wild in the Country,” Philip Dunne, told me the studio made him put in songs for Presley that really didn’t belong in the drama. That was typical of an unfortunate movie career, Dunne lamented, that never really provided Presley with an opportunity to develop the incipient acting talent that Dunne admired. Here is where the Colonel really was of no help to Presley, though Messrs. McDonald and Terrill do not say so.

Mr. Rollyson is the author of “American Biography” and biographies of Marilyn Monroe, Dana Andrews, Walter Brennan, and Ronald Colman.