Santa Monica Establishes $3.5 Million Reparations Fund Despite ‘Dire’ Financial Outlook

By LUKE FUNK

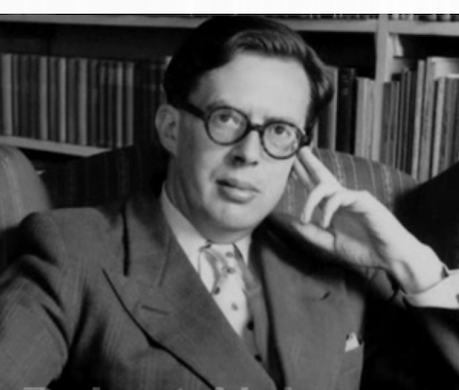

|From moment to moment, what Robert Aickman experienced and what he imagined are hard to separate. It is a virtue of this biography that it shows how, for Aickman, experience was what he imagined.

Already have a subscription? Sign in to continue reading

By LUKE FUNK

|

By MATTHEW RICE

|

By DONALD KIRK

|$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

By continuing you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.