In ‘Manet/Degas,’ a Ravishing Fusion of Frenemies, Metropolitan Museum Set To Thrill New York

The two titans, who painted at the cusp of the modern era, are, in partnership with the Musée d’Orsay, up at the Met in a true triomphe.

Rarely has there been a more ravishing fusion of frenemies than the one that can be enjoyed at “Manet / Degas,” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through the first week of next year. Born two years apart, Édouard Manet and Edgar Degas were founding fathers of modern art, tag-team virtuosos who made France the main stage of 19th century culture. The show, a collaboration between the Met and the Musée d’Orsay, is a Parisian triomphe.

To ask the crass: Was one better than the other? As one of the show’s curators, Stephan Wolohojian, put it at the press preview, “there was no game and there were no rules.” There was plenty of work, though, with 160 pieces on display here, the bulk of them from the Met and the d’Orsay, with contributions from more than 50 institutions and private collectors. It’s gigantic, involved, and sure to draw throngs.

The duo’s origin story is almost too resonant to be real. The Met reports that they met at the Louvre, where Degas was etching in front of a portrait then believed to be by the Spanish maestro Diego Velázquez. Manet joined him in a partnership in paint, but the twisted arc of their relationship would be at home in that great 19th century genre, the novel. They moved in asymmetric tandem, like two planets in irregular orbit. Think chiaroscuro contact.

The archive of their affections and antagonisms is not extensive, amounting to sparse correspondence. The dyad, though, comes into focus from stray remarks to mutual friends and observations from contemporaries. Manet never painted Degas, but a group of arresting portraits featuring a photographic acuity surfaces how Degas saw Manet. This suite of seven etchings and drawings offers a model of friendship as sustained attention.

“Monsieur and Madame Edouard Manet,” painted by Degas between 1868 and 1869, comes from a municipal museum in Japan, but deserves Manhattan’s bright lights, as well as ones of a more noirish tint. The painter is depicted sprawled on a couch. His wife Suzanne is on the piano, her skirt rippled. She is cut off, though, the painting gashed in the middle. Manet defaced it, for reasons unknown.

Degas reclaimed it, and it hung for decades in his apartment. This was the brand of uneasy intimacy that characterized the relationship at its zenith. Both sons of the bourgeoisie, they traveled to Italy and apprenticed themselves to the Renaissance masters of the distant past — there is a Manet after Titian, and a Degas after Mantegna. Degas’s “Memory of Velázquez” shows the Spaniard painting “Las Meninas.” Both Manet and Degas would both eventually make history by breaking with it.

If the pair’s links to art’s ancien régime provided a shared point of departure, 1865 saw a rupture. The headliner is “Olympia,” an oil work of enduring scandal because it transposes the conventions of the mythological Venus to the boudoir of a woman you know. It feels like she is more looking than looked at and possessed of a sensuality that marks the work from its Botticelean and Titianian antecedents. She is an innovation and an invitation.

That same year Degas painted the quieter but no less radical “A Woman Seated Beside a Vase of Flowers.” A bequest of the Havemeyers, sugar barons who bequeathed their name to a now-trendy street at Williamsburg, it is something between a still life and a portrait, brought into sharp foreground focus. The flora dwarf the face, thought to belong to the mother of a childhood friend. In its studied casualness, it seems to anticipate the photograph. The flowers resemble another face, blooming and petalled.

The portrait, that old warhorse, here finds fresh focus. Renditions by Manet of Émile Zola and Stéphane Mallarmé bring the literary titans close while gesturing to the mystery of creativity. “A Cotton Office in New Orleans,” from a trip to the South taken by Degas after the American Civil War, plunges us into the commotion of commerce, a delightful dip into the business of the bayou. Degas likely felt at home in the one-time Napoleonic domain.

On view are paintings by both authors of their parents, images flecked with the mix of intimacy and intimidation one would expect of the prosperous and expectations-laden milieu in which both painters were raised. They both swerved from a future in the law to aesthetic pursuits. Authority on a different scale is captured by Manet in an aquatic reverie, “The Battle of the USS Kearsage and the CSS Alabama,” so vivid as to inspire seasickness.

Of peculiar vividness is Manet’s “Berthe Morisot With a Bouquet of Violets.” Morisot was Manet’s sister-in-law, and an accomplished painter herself. The resulting work is charged by the circumstance of one artist rendering another through the scrim of their shared medium. There is nothing, though, that is precious or meta about it. It’s gorgeous, Manet’s evocative black paint framing her fine features. She’s in mourning weeds, but her gaze is far from grim.

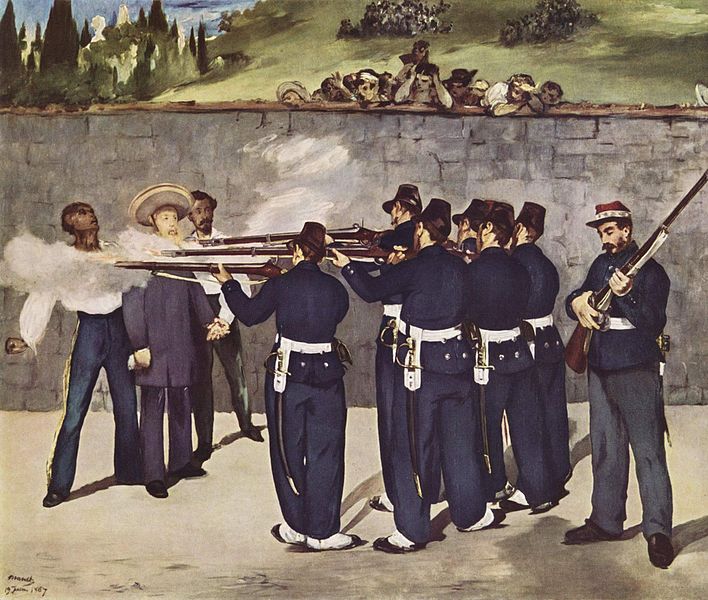

Degas outlived Manet by three decades. In “The Execution of Maximilian,” Manet depicted the 1867 murder by firing squad of the emperor of Mexico, appointed by Napoleon III. Too close to the political marrow to be shown, it was cut into pieces and sold off after Manet’s death. It was, of course, Degas who reassembled what had been scattered, and who hung the work in his residence, just as it hangs here, at once an exaltation and an execution.