Is the Case Against President Trump Ready for Prime Time?

One question the January 6 committee has not resolved is whether the events of January 6 constituted an ‘insurrection.’

The January 6 Committee will hold its last public hearing on Thursday, ostensibly wrapping up a series of televised sessions designed to pressure the Department of Justice to hand up criminal charges against President Trump.

Thursday’s hearing, like the one that launched the committee’s work last month, will be broadcast in primetime. It will focus on Mr. Trump’s conduct on January 6, 2021, specifically his response as rioters breached the Capitol walls and made the building their own until order was restored.

Absent on Thursday will be the committee chairman, Representative Bennie Thompson, who has Covid. Also missing will be text messages requested by the committee from the Secret Service relating to January 6. According to the Washington Post, those messages were purged in an agency-wide reset and are “unlikely to ever be recovered.”

The hearings have thus far made a splash, with dramatic disclosures and robust viewership. Even as they have galvanized Democrats seeking to hold Mr. Trump’s feet to the fire, they have opened fissures between the committee and DOJ over the handling of evidence as well as within Democratic legal circles over the best strategy for translating publicity into verdicts.

One question the committee has not resolved, however, is in some sense the most basic one: Whether the events of January 6 constituted an “insurrection.” If they did, a whole host of prosecutorial avenues will open up for Democrats, who will be able to portray January 6 as a day that in its severity echoes rebellions of the past.

In addition to criminal charges, a finding of insurrection would be a boon to efforts to mobilize the Disqualification Clause of the 14th Amendment to block Republicans from the ballot. In addition to efforts underway targeting representatives nationwide, the group spearheading that push, Free Speech for People, a leftist organization, has now asked 50 secretaries of state to commit their offices to disqualifying President Trump.

Federal law establishes for “whoever incites, sets on foot, assists, or engages in any rebellion or insurrection against the authority of the United States or the laws thereof, or gives aid or comfort thereto” the punishment of a prison sentence and ban from holding office, but leaves insurrection undefined. That ambiguity is native to the Constitution, where insurrection is mentioned but not explicated.

In President Trump’s second impeachment trial, the sole count levied against him was “incitement to insurrection.” One of his lawyers, Michael van der Veen, conceded “the question before us is not whether there was a violent insurrection of the Capitol. On that point, everyone agrees.”

In fact, not everyone did agree that the violence at the Capitol amounted to an insurrection, and the Senate determined that the former president was not guilty of inciting an insurrection.

Webster’s Dictionary defines “insurrection” as “a rising against civil or political authority; the open and active opposition of a number of persons to the execution of a law in a city or state. It is equivalent to sedition, except that sedition expresses a less extensive rising of citizens.”

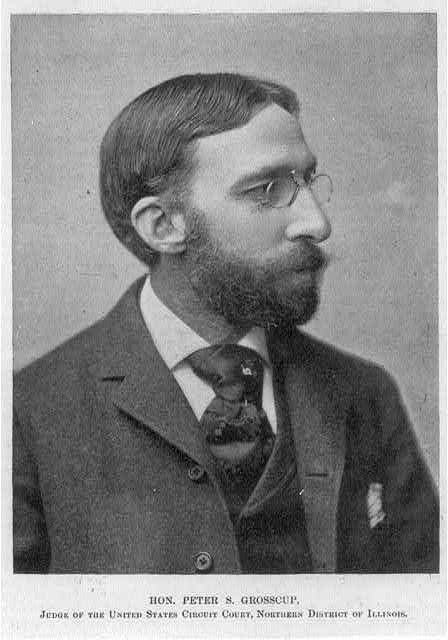

In 1894, a United States district court judge, Peter S. Grosscup, instructed a grand jury, in a case involving the Pullman Strike, that to find an insurrection it is “necessary, however, that the rising should be in opposition to the execution of the laws of the United States, and should be so formidable as for the time being to defy the authority of the United States.”

In stirring language, the judge affirmed that “neither the torch of the incendiary, nor the weapon of the insurrectionist, nor the inflamed tongue of him who incites to fire and sword is the instrument to bring about reforms.” This aversion to radicalism coexisted with Judge Grosscup’s sense that “the opportunities of life, under present conditions, are not entirely equal.”

Judge Grosscup’s jury instructions, recorded in case law as In re Charge to Grand Jury, add that “It is not necessary that there should be bloodshed” for there to be an insurrection. In its wider effort to classify January 6 as an insurrection, Free Speech for People maintains that the rioters on that day “achieved a feat not even the Confederate rebellion managed: seizing the United States Capitol and disrupting the peaceful transfer of power.”

Even in the absence of a judicial finding on the matter, key organs of the American government appear to agree. The DOJ began using the word in the immediate aftermath of January 6, and Congress castigated “insurrectionists” in its statement awarding Congressional Gold Medals to Capitol Police officers who were on the scene that day. It has been repeatedly invoked by President Biden.

Prosecutors have yet to charge anyone with insurrection related to January 6. While insurrection has not yet been put to the courtroom test, its cousin — seditious conspiracy — has now been charged over a dozen times in connection with January 6. That charge overlaps slightly with insurrection, and the fate of those cases will likely offer a preview of what looms on the legal horizon for Mr. Trump.