Can Trump ‘Nationalize’ Elections?

By THE NEW YORK SUN

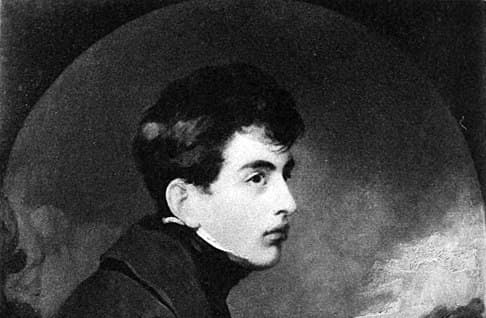

|The poet appears in quite a different aspect in Anne Eekhout’s evocative novel, where in addition to being ebullient and mercurial, he is magnetic. Andrew Stauffer’s entry, meanwhile, is somewhat gimmicky.

Already have a subscription? Sign in to continue reading

$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

By continuing you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.

By BRADLEY CORTRIGHT

|