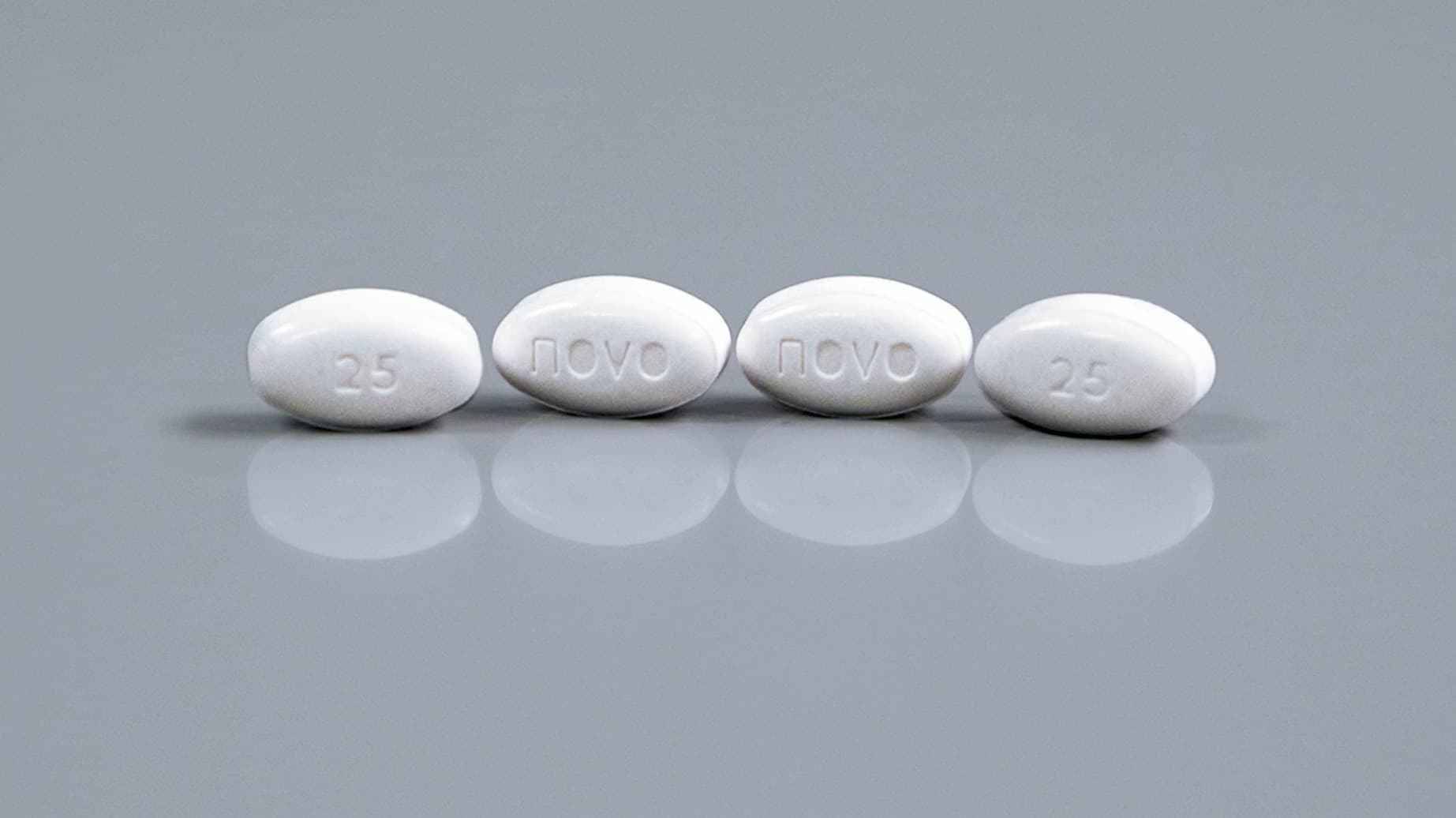

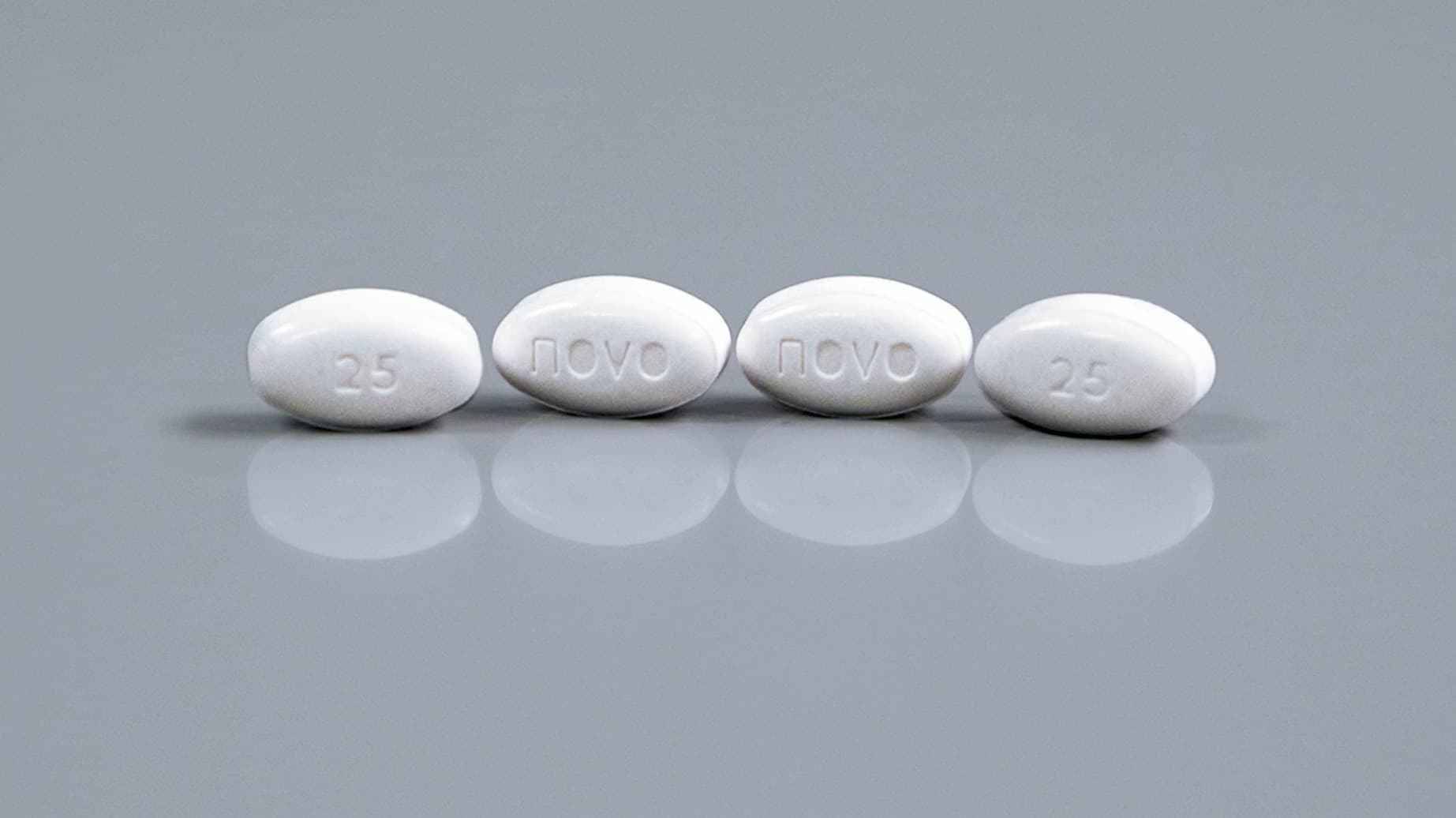

Him & Hers in Hot Water Over Knockoff Version of Wegovy Weight Loss Pills

By LUKE FUNK

|The painter was a master of evoking truth from the raw and rather lumpish material of reality, a citizen of the world, an innovator whose vocabulary is drawn from tradition — we dare say a perfect artist. This may be a perfect exhibition.

Already have a subscription? Sign in to continue reading

By LUKE FUNK

|

By BRADLEY CORTRIGHT

|

By THE NEW YORK SUN

|$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

By continuing you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.