Joyce Carol Oates, Reluctant Subject

The author’s second husband, who died in 2019, is, if not the star of ‘A Body in the Service of Mind,’ then its most amiable player. The audience can’t help but smile when he saunters into its purview.

Following the premiere of “Joyce Carol Oates: A Body in the Service of Mind” at the IFC Center, Ms. Oates took to the stage along with director Stig Björkman and a fellow author, Jonathan Santlofer. In short order, she made it obvious that public relations is not her forte.

After likening the film to an “autopsy,” Ms. Oates repeatedly described the experience of watching herself on-screen as “excruciating.” Almost as significant a calumny, she said, was the dearth of cats in the movie. Still, Ms. Oates had to admit that the ending of the film did right by the lone cat that was on display.

The author did have other good things to say about Mr. Björkman’s documentary. She was pleased by the emphasis given to Lewis Carroll’s “Alice in Wonderland” and the role it played in shaping her literary aesthetic. On the whole, though, Ms. Oates was equivocal.

Mr. Björkman told the story of how he had been broaching the idea of a documentary for 16 years — to no avail and much frustration. Ms. Oates did capitulate, not a little begrudgingly, upon the insistence of her second husband, Charles Gross.

Gross died in 2019. What he might have thought about the completed film is a matter of conjecture, but there’s no doubting that Gross is, if not the star of “A Body in the Service of Mind,” then its most amiable player. A professor of neuroscience and an enthusiastic traveler — unlike Ms. Oates, an admitted homebody — Gross shuffles through Mr. Björkman’s film with a winning disregard for the camera. The audience can’t help but smile when he saunters into its purview. Ms. Oates, in contrast, can’t shake off her awkwardness at being the center of attention.

The notable exception is the scene in which Ms. Oates and Gross are seated next to each other recounting a past incident. Gross teases his wife, purposefully fumbling facts and timelines, and does so in a sly but deadpan manner. Ms. Oates tries to correct the course of the conversation, but can’t help herself from laughing, sometimes breathlessly, at Gross’s tomfoolery. Here, you think, are two people who love each other. This is the kind of moment documentary filmmakers dream of: Never again do we see Ms. Oates quite as unguarded.

Otherwise, Mr. Björkman’s movie is — well, it’s okay. Although he avoids trotting out the standard array of talking heads, “A Body in The Service of Mind” doesn’t much test the boundaries of the documentary format, preferring gentle hagiography to something more intensive or far-reaching. At IFC, Ms. Oates wished there had been more time devoted to boxing. Her fascination with “our most dramatically ‘masculine’ sport, and our most dramatically ‘self-destructive’ sport” stems from her father’s enthusiasm. Young Joyce, don’t you know, was raised on the stuff.

Politics are given undue priority and mar the film. True, Ms. Oates’s fiction has often been predicated on hot-button issues. The environmental crisis at Love Canal, the Chappaquiddick scandal, the deification of Marilyn Monroe and the Detroit riots — please, Ms. Oates, not “urban disturbances” — were pivotal as prompts for her books.

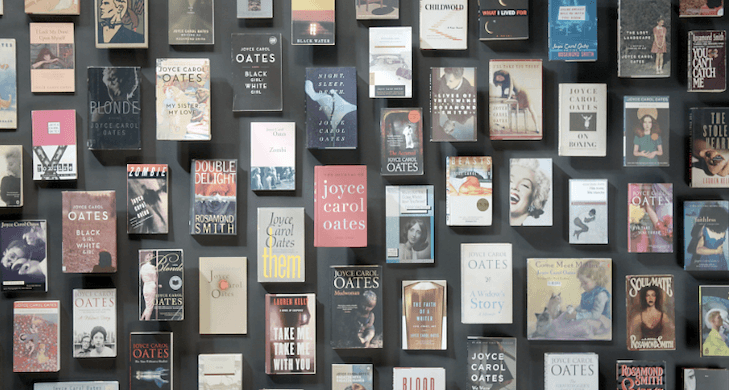

Yet the work is more encompassing than those subjects and considerably more intimate. Did you know that she wrote thrillers under the pseudonym Rosamond Smith? “A Body in The Service of Mind” only glances at this tangent of Ms. Oates’s output.

As a filmmaker on foreign soil, Mr. Björkman can’t help but have his own particular spin, but would that more attention had been paid to the author’s derring-do as a literary stylist, on her somewhat scarifying drive to write, write, write. Admittedly, the diligent crafting of words isn’t as readily cinematic as, say, news footage from the 1960s, but Ms. Oates’s claim of being a formalist remains largely unexplored.

Fans of her books will cheer on “A Body in The Service of Mind.” Those who are less familiar with her corpus will wonder why the brainy lady at the core of the film put herself in a situation that runs contrary to her nature.