Karl Lagerfeld, the Met’s New Patron Saint, Steals the Show

Haute couture will be hanging, at least for a while, with Rembrandt and Titian.

Long after the red carpet is pulled up and Rihanna has jetted off, Karl Lagerfeld — or his designs — will linger at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, haute couture hanging with high Rembrandt and Titian. The more than 200 items the Costume Institute has put on display recall the bon mot of another man for whom style was substance, Oscar Wilde, who ordained, “One should either be a work of art, or wear a work of art.”

The show, titled “Karl Lagerfeld: A Line of Beauty,” will adorn the museum’s Great Hall through the middle of July. It was inaugurated at the Met Gala, whose presiding genius is the longtime editor of Vogue, Anna Wintour. While Lagerfeld, who died in 2019, has come under fire for comments like “no one wants to see curvy women,” Ms. Wintour has defended his legacy.

Not everyone is comfortable with Lagerfeld’s canonization. The actress Jameela Jamil took to Instagram to write, “Hollywood and fashion said the quiet part out loud when a lot of famous feminists chose to celebrate at the highest level, a man who was so publicly cruel to women, to fat people, to immigrants and to sexual assault survivors.” She added that the choice shows “how selective cancel culture is within liberal politics.”

Lagerfeld, who was born at Hamburg during the closing days of the Weimar Republic, would for three decades serve as Chanel’s creative director, and occupy the same position at Fendi. He also created his own eponymous line, which he hoped would embody “intellectual sexiness.” His star burned brightest in the 1970s and 1980s, when he resurrected Chanel from the doldrums. In 2013, he noted that he would marry his pet cat, Choupette, if it were legal.

“A Line of Beauty” is an apt title for a man who both crossed the line and served as one of beauty’s self-appointed enforcers. The Met explains that its focus is on Lagerfeld’s “unique working methodology” and “stylistic vocabulary” as distilled in “through lines,” or the aesthetic and conceptual themes that concerned him for decades starting in the 1950s. Brushing off criticism like that offered by Ms. Japil, the Met calls Lagerfeld “singularly impactful.”

Lagerfeld quipped, “Sweatpants are a sign of defeat,” and you won’t find any of them at “A Line of Beauty.” Focus is on the designer as a draftsman. The exhibit’s title comes from the 18th century British artist William Hogarth, who defined the “line of beauty” as a “serpentine line,” a “waving line,” a “winding line,” and “the line of grace,” all in contrast to the more prosaic straight and curved lines. Hogarth was after the human shape.

The Met judges that Lagerfeld is “much too magnanimous” to be as unwaveringly committed as was Hogarth to the S-shaped line above all other marks on the page. “Sketch of Chanel dress,” from 2019, won’t remind anyone of the bawdy brilliance of Hogarth’s “A Rake’s Progress,” but its lively strokes and scribbled notes — cinched waist and long arms, with a white dress adorned with flowers — straddle the line between work and work of art.

Another pleasing correspondence crackles between “Sketch of Chanel coat,” from 2014 and 2015, and images of that same coat from the runway. Both the coat and the sketch are anchored by a horizontal line of buttons, a geometric rigor nicely set off by cutouts that give way to sleeves and shoulders of gold. The pattern of snow white and luminous aureate convey the impression of a winterscape, glinting with chilly splendor.

More abstract is “Sketch of Fendi dress,” from the spring and summer season of 1997. The sketch is minimalist, built from just a few flicks of the wrist, all geometries of straight lines and right angles. The payoff comes with the completed dress, which looks like a second skin, the model’s bare arms contrasting with the black and white palette that suggests a maze by way of Franz Kline — a reminder that Lagerfeld’s work was largely built on the female form.

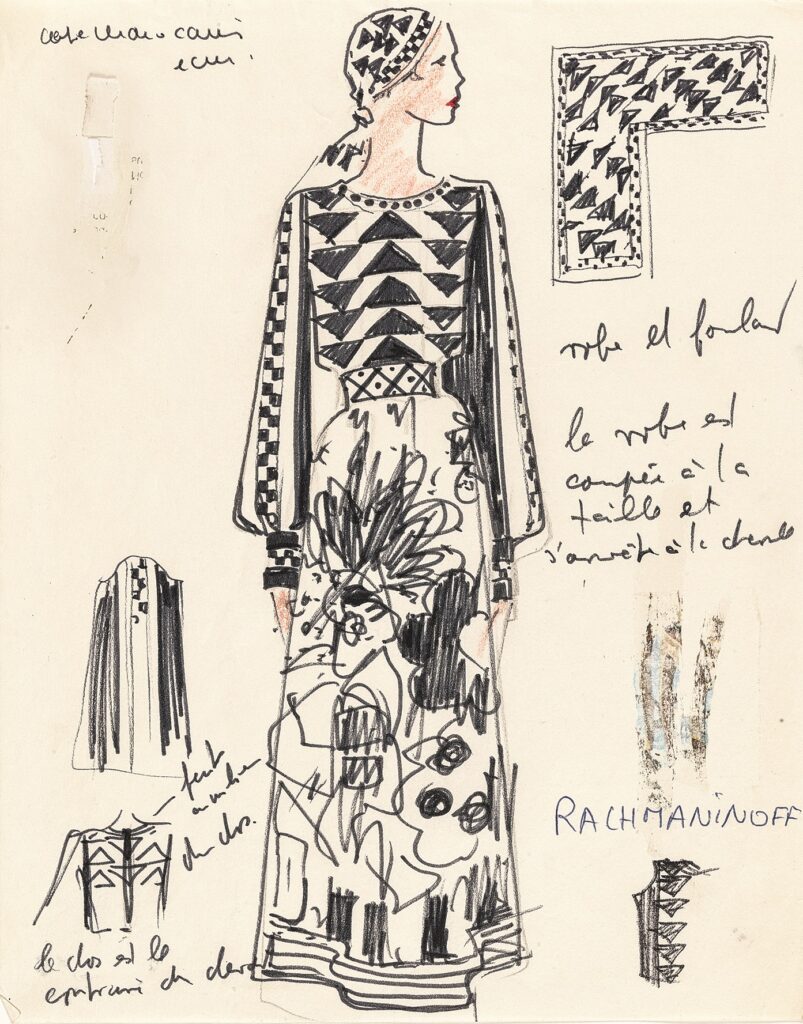

A “‘Rachmaninoff’ dress,” designed for Chloé in 1973, still feels avant-garde, its triangles giving way to two dancing figures and images of the piano, an homage to the Russian composer that captures something of his music in fabric. The distinction between minimalism and maximalism appears misplaced when applied to this dress, an exercise in lush imagination that suggests rather than insists. It would turn the right heads on a night out.

Lagerfeld described Chanel’s autumn/winter line from 2014 and 2015 as “Le Corbusier goes to Versailles,” and there is something in his style — in life and in art — of both the Sun King and the brutalism of the previous century. His oeuvre impresses, but it can be difficult to detect a soul, and a static appears to have seeped in as Lagerfeld became not just a designer, but a brand. Icons rarely make great art. Eventually, though, they steal the show.