Hamas, Defying Trump, Eyes Keeping Control of Gaza

By THE NEW YORK SUN

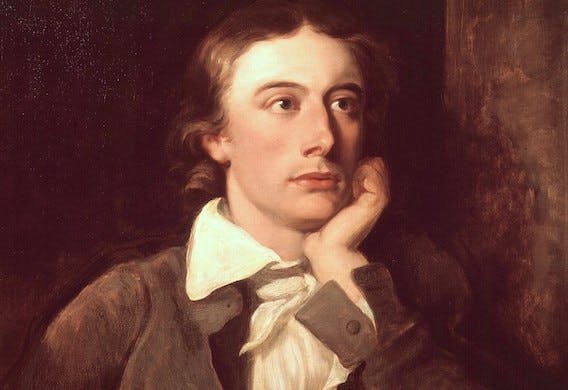

|If you have an impression of an ethereal poet, scrub that from your consciousness.

Already have a subscription? Sign in to continue reading

By THE NEW YORK SUN

|

By CAROLINE McCAUGHEY

|

By JOSEPH CURL

|$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

By continuing you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.