Gustav Klimt’s Landscapes, on View at the Neue Galerie, Show He Was as Glorious With Green as Gold

The Austrian master painted the countryside with the same sparkle and gusto with which he rendered Viennese beauties.

‘Klimt Landscapes’

The Neue Galerie, 1048 5th Ave, New York, NY

Through May 6, 2024

The painter Gustav Klimt is indelibly associated with the color gold, but “Klimt Landscapes” offers a contrarian take — here, the Austrian goes green. Just feet from his “Portrait of Adele Bloch Bauer I,” — the famed Woman in Gold — a more vertiginous and verdant phase unfolds. These five late works transmit something of the retiree’s leisure and the amateur’s delight, though none of the dilettante’s distraction. They are an invitation to gander at green.

Call it Kimt’s green gambit, the successor to his golden style. The show comprises works of Klimt’s sommerfrische, or summer holidays, in the countryside. They are the harvest of the last two decades of Klimt’s career, and were created for the painter’s own pleasure, not the delight of Vienna’s dukes and dames. These paintings of land rather than ladies suggest that Klimt was alert to the trends in France, where the pull of pure pigment was strong.

Klimt’s career overlaps nearly entirely with the fin de siècle, an artistic moment animated by a sense of an ending that could have had no sense of how bloody that ending would be at the Somme and Verdun. Born in 1862 and dead in 1918, he attained his greatest fame as a painter of women. He completed about one large scale rendering of a woman a year, often in an Art Nouveau style — flat, decorative, ravishing, gold. The contemporary market adores him.

The English poet Andrew Marvel, from the 17th century, writes in his poem “The Garden” that the mind can, if it’s feeling fecund, get busy “annihilating all that’s made into a green thought in a green shade.” That is what Klimt appears to have been doing in “Park at Kammer Castle,” from 1909. Here the color occupies the entire palette, a ubiquity that allows for a dizzying array of shades and variations. It recreates the spectrum in itself.

Gustav Klimt in the garden of his studio at

Josefstädter Strasse 21, April/May, 1911.

Moriz Nähr via Neue Galerie.

“Park” retains just enough contrast to be legible, and just enough blurriness to deliver the woozy sense of a summer afternoon spent lollygagging. The trees are pointillist — hives of life both macro and micro — but the true triumph is how Klimt paints the water, its surface at some middle point between crystalline and marshy. It too, is green, a serene species of grass. Some of Claude Monet’s most exquisite “Water Lilies” are contemporaries.

“Forester’s House in Weissenbach II (Garden),” from 1914, is so cozy it feels as if it could fit on a postcard. The windows are thrown open, welcoming the breeze. The walls are festooned with vines and the window sills are laden with flowers. The painting eschews the sublime for the souvenir. It could, though, provide inspiration for your next AirBnb booking. Its companion, “Forester’s House in Weissenbach II,” is also a little rotely rural.

Kimt touches a more daring place in “The Park,” another work from 1909. The foliage is arresting, almost overwhelming. Grandeur is no stranger to the garden here, and Klimt appears to be pursuing color beyond the genre of landscape altogether. If you squint, you might be able to see what is to come — Jackson Pollack’s daring drips and Mark Rothko’s bands. This chronicler of the haut bourgeois sensed abstraction was just around the bend.

A more conventional excellence is achieved in “Kammer Castle on the Attersee IV,” from 1910. Foreground and background are adroitly rendered, and the castle itself is pleasingly akimbo, an effect enhanced by the pile’s reflection in the water at the painting’s center. It conveys something of a chance sight line and an unexpected angle. It’s closer to, say, Nicolas Poussin’s “Landscape with a Calm” than the last century.

This show — and the entirety of the Neue Galerie — is a legacy and vision of the Lauder family. The landscapes are supplemented with a generous helping of context. These include paraphernalia from the Vienna Secession, an avant-garde movement of artists that included Klimt, as well as drawings and early photographs, the then relatively new medium that was already altering what it means to see and capture. One even finds a replica of Klimt’s smock.

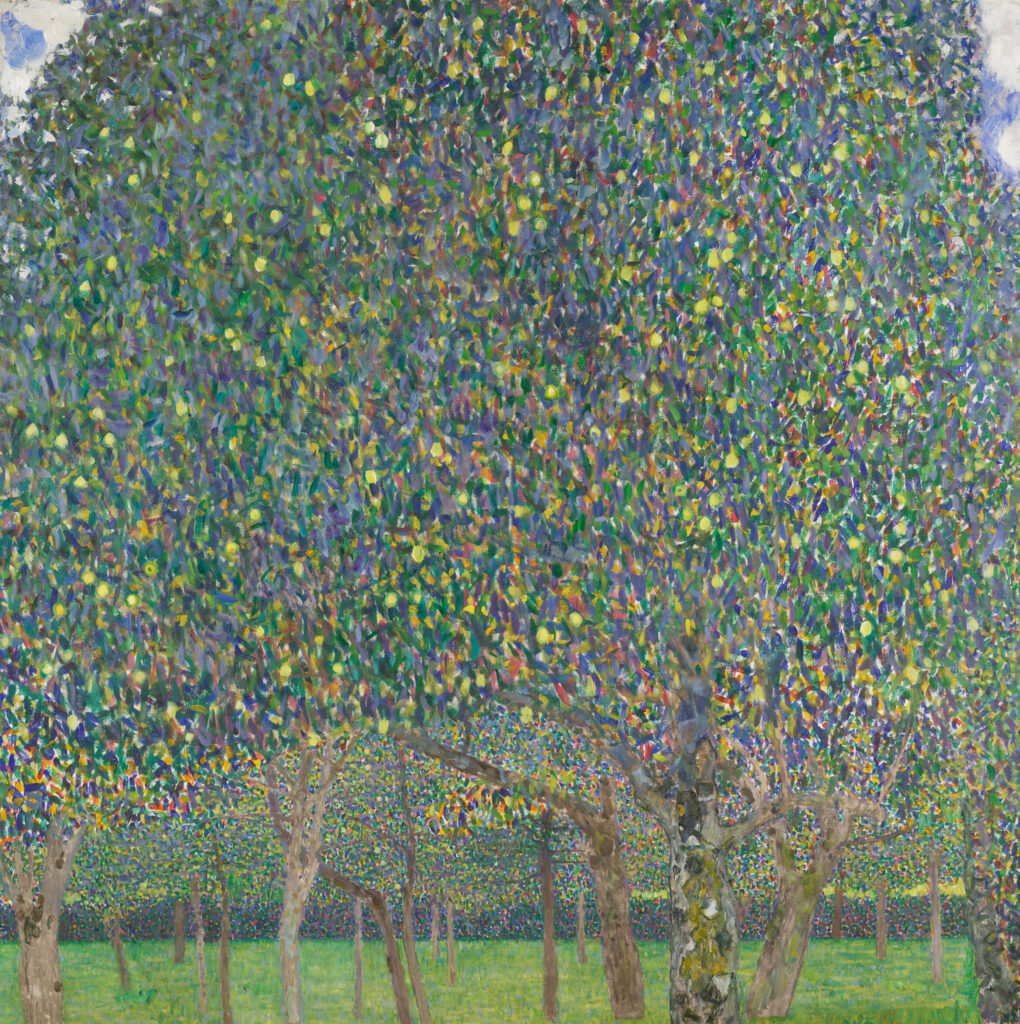

Pear Tree (Pear Trees), 1903, Gustav Klimt.

Harvard Art Museums / Busch-Reisinger Museum, via Neue Galerie.

If time is short, linger in front of the “Portrait of Adele Bloch Bauer I” on the gallery’s second floor, and reflect whether the $135 million Ronald Lauder paid for it at auction might almost be called a bargain. Then, take in all that annihilating and energizing green. Finally, find refreshment — a linzer torte or bit of herring — along with European broadsheets, at Café Sabarsky, on the ground level. Afterward, take in Frederick Law Olmsted’s own vision in green, Central Park, just across the street.